Heading Back to the Moon: Project Artemis II

For the first time in more than half a century, humans will leave low Earth orbit and fly close to the Moon—without landing. Artemis II is meant to be the next step toward returning astronauts to the lunar surface, but major - and costly - challenges still lie ahead.

31 January 2026

|

15 minutes

|

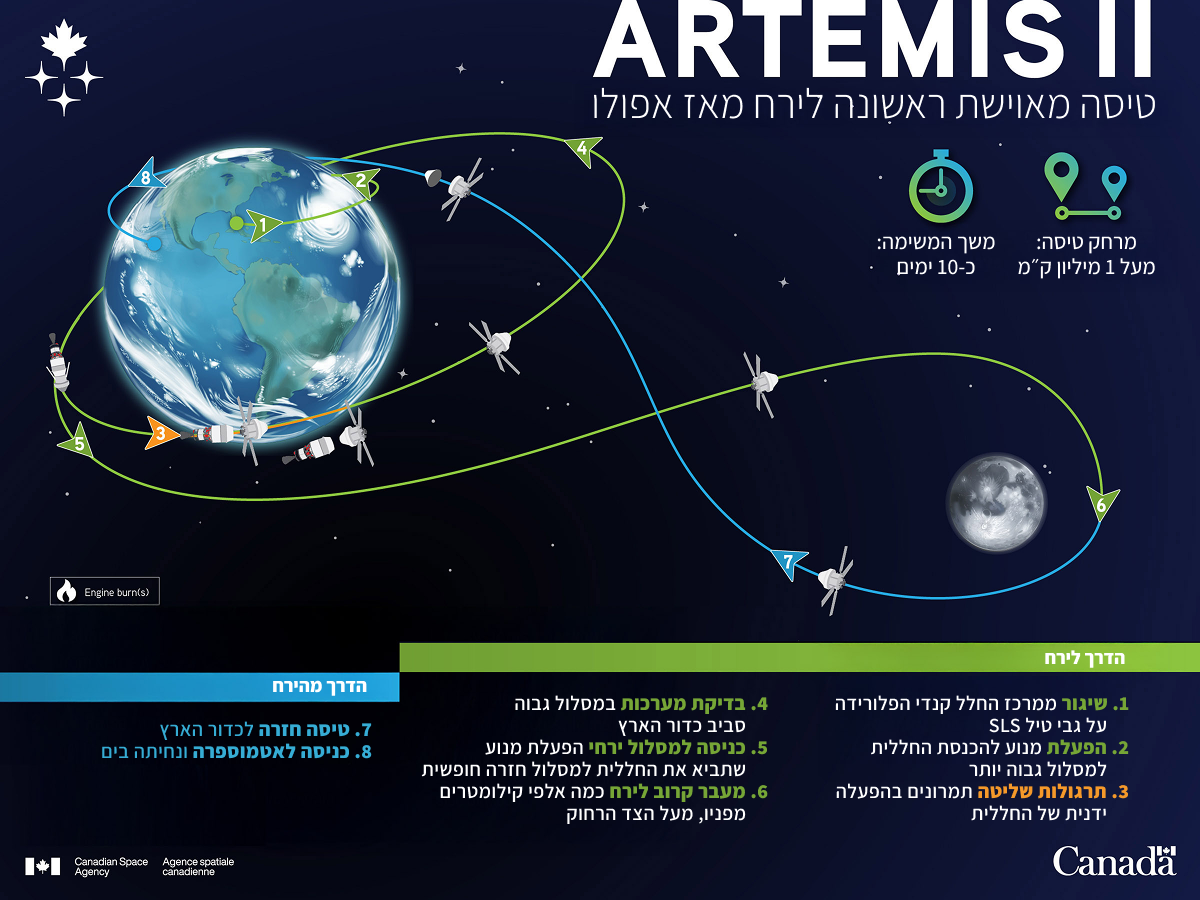

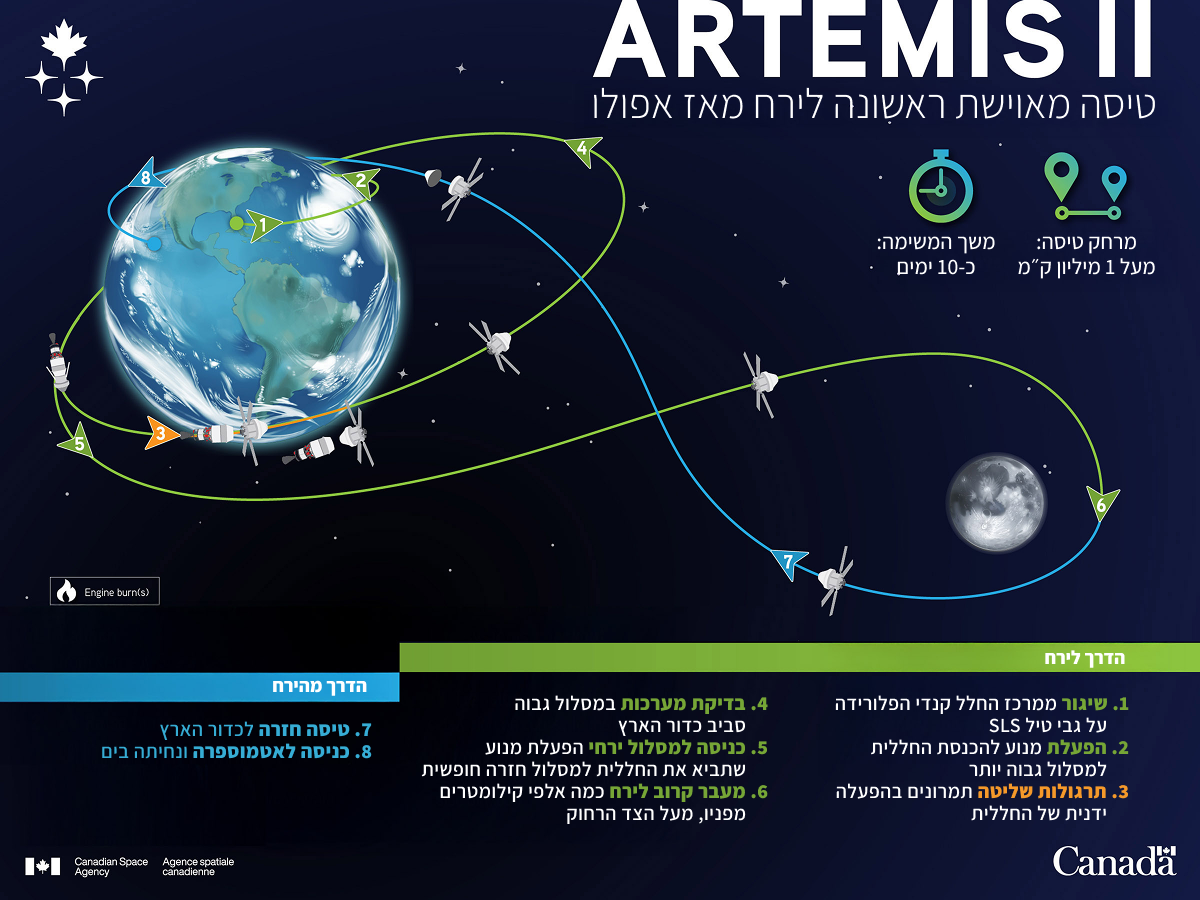

If there are no unexpected delays, four astronauts will launch toward the Moon on February 7. They won’t land, and they won’t enter lunar orbit – only fly past at a distance of about 6,500 kilometers. Even so, it will be the first time in more than 52 years that humans have left low Earth orbit and entered the gravitational field of another celestial body. It will also be the first time a lunar mission is flown in a spacecraft carrying four people – Apollo crews numbered three – and the first time a woman, a Black astronaut, and a non-U.S. citizen travel to the Moon.

The flight will also mark the first crewed launch of the SLS rocket and the first crewed mission of the Orion spacecraft. If all goes as planned, it could set additional records, including the farthest distance humans have traveled from Earth and the highest-speed atmospheric reentry ever attempted on a crewed spaceflight.

A successful mission is expected to pave the way for Artemis III, which aims to return humans to the lunar surface, and for follow-on missions that could eventually establish a base or research station on our nearest celestial neighbor. But significant hurdles remain – some of them formidable – for NASA and the broader Artemis program.

A Legacy Spacecraft

The Artemis program, through which the United States aims to return humans to the Moon, began just over three years ago. In November 2022, the uncrewed Orion spacecraft flew around the Moon as part of Artemis I. At the time, NASA projected an Artemis II launch in 2024 and a first crewed landing – on Artemis III – in 2025. Those timelines have since slipped: certifying Orion for crewed flight has taken longer than expected, largely because of problems with its life-support system and, in particular, unexpected damage to its heat shield during Artemis I.

Orion is the last major holdover from the Constellation program, launched by the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush in 2004 with the aim of returning humans to the Moon. President Barack Obama canceled Constellation in 2010, but allowed development of the spacecraft to continue—and progress remained sluggish for years. In shape and many basic characteristics, Orion resembles the Apollo capsules, though it is slightly larger and, of course, far more technologically advanced than 1960s-era hardware. The spacecraft flew its first test mission in 2014, but development accelerated only after President Donald Trump revived a formal push to return to the Moon during his first term.

That long, stop-and-start history has made Orion one of the most expensive spacecraft ever built: about $20 billion has been spent on its development. And unlike today’s broader shift toward reusability, Orion is fully expendable – each mission requires a new spacecraft – further driving up the program’s overall cost.

The spacecraft consists of a crew module, where the astronauts live, and a service module provided by the European Space Agency as part of its partnership in the program. The crew module is a truncated cone about five meters in diameter. It houses the command-and-control systems as well as the equipment the astronauts will use during the mission – from food and computers to navigation and communications gear, and even a compact toilet system. Orion can be flown from mission control or manually by the crew, using a series of touchscreens reminiscent of the cockpit of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner.

The habitable volume is about nine cubic meters – roughly the interior space of a commercial van – where four people are expected to live and work for the mission’s ten days. The spacecraft is designed for missions of up to 21 days with a full crew, and can remain operational for up to six months while docked to a space station.

The European-built service module includes deployable solar arrays to generate electricity, tanks for water and oxygen, and the main engine that will place the spacecraft on its planned trajectory – and, on future missions, enable entry into lunar orbit as well. Before reentry, the service module separates and burns up in the atmosphere; only the crew module, carrying the astronauts, returns to Earth, as was the case with Apollo.

Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen presents the Orion spacecraft:

To launch Orion, NASA developed a dedicated rocket called the Space Launch System, or SLS. In its current configuration, the 98-meter-tall rocket can send a payload of more than 27 tons toward the Moon; a future version is expected to increase that to about 46 tons. Development has been underway for roughly 15 years and has cost U.S. taxpayers about $30 billion so far. Like Orion, SLS is rooted in older technology: many of its components are derived from the Space Shuttle program, which ended in 2011. Its four main engines – also inherited from the Shuttle – burn liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, a propellant combination that has largely fallen out of favor due to the difficulties of handling it. Artemis I, for example, was repeatedly delayed due to hydrogen leaks. SLS is also fully expendable, with no major components reused—an approach that drives operating costs sharply upward.

Like the Space Shuttle, SLS uses two solid-fuel boosters at liftoff to provide additional thrust and speed to carry the spacecraft into space. The boosters – slightly larger than those used on the Shuttle – separate and splash down in the ocean a little over two minutes after launch. About a minute later, Orion will jettison the launch abort system, a rocket-powered emergency escape tower mounted atop the spacecraft and designed to pull the crew capsule away in the event of a dangerous malfunction early in flight. The rocket’s first stage burns for about eight minutes, then separates at an altitude of roughly 160 kilometers. Orion remains attached to the second stage, about 14 meters long, whose engine is also powered by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.

If everything goes as planned, the crew will lift off on February 7. The SLS rocket with the Orion spacecraft atop it during rollout to the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 17, 2026. Photo: Aubrey Gemignani/NASA.

Dreams Coming True

Chosen to command Artemis II is astronaut Reid Wiseman, 50. A former U.S. Navy aviator and test pilot, Wiseman was selected as a NASA astronaut in 2009. He flew a roughly six-month space mission aboard the International Space Station in 2014, and in 2020 was appointed to a two-year term as Chief of NASA’s Astronaut Office.

The mission pilot will be Victor Glover, 49. Selected by NASA in 2013 after a career as a U.S. Navy captain and test pilot, he holds a master’s degree in engineering. Glover flew a roughly six-month mission on the International Space Station in 2020–21 and served as pilot on the first operational Crew Dragon mission to the station, following the spacecraft’s test flight. Shortly before NASA announced the Artemis II crew in 2023, Glover told the Israeli news site Ynet during the Israeli Space Week: “To be part of the crew that might reach the Moon—it’s so far beyond dreams and anything I ever dreamed.”

The mission specialist is Christina Koch, 47, who also joined NASA’s astronaut corps in 2013. She holds a master’s degree in electrical engineering and previously worked in research at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In 2019–20 she completed a nearly year-long mission aboard the International Space Station and still holds the record for the longest single continuous spaceflight by a woman – 328 days. During that mission, she and astronaut Jessica Meir carried out the first all-female spacewalk.

Completing the crew is a second mission specialist, Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen—the only one for whom this will be a first spaceflight. Canada received a seat on the mission through its cooperation with the United States in the program, and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) selected Hansen from among its astronauts. Now 50, he served as a fighter pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force and has taken part in cave-exploration training under a European Space Agency program designed to prepare astronauts for underground work. He has also participated in an extended underwater mission simulating life and work in space.

Unusually, NASA did not name a full backup crew for the mission, selecting instead a single astronaut who could replace any of the four primary crew members if needed. NASA’s backup is Andre Douglas, 40, who holds a PhD in systems engineering, was selected as an astronaut in 2021, and has not yet flown in space. The Canadian Space Agency chose Jennifer Gibbons as Hansen’s backup; she holds a PhD in engineering, joined the agency in 2017, and has also not yet flown in space.

The space agency announced the crew in April 2023, so the four astronauts – and their two backups – have been training for this flight for nearly three years.

Meet the crew: a short NASA video introducing the four Artemis II astronauts.

Free Return

After reaching space—just over eight minutes after launch—the second-stage engine will fire to place the spacecraft into low Earth orbit, where the crew will begin initial checks of onboard systems. About an hour later, near the end of the first orbit around Earth, the engine will ignite again, sending the spacecraft into a highly elongated elliptical orbit with an apogee of about 70,000 kilometers above Earth. One circuit on this trajectory takes almost a full day. During that time, the crew will test additional systems—especially navigation, since the spacecraft will be flying beyond the reach of GPS satellites—as well as communications, including links with NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), which is designed to communicate with distant spacecraft.

Immediately after the burn that places Orion into this orbit, the spacecraft will separate from the rocket’s second stage. The stage will have finished providing propulsion—but not its role in the mission. Orion’s pilots will then conduct spacecraft-handling drills, approaching the second stage and backing away along preplanned paths, to test the spacecraft’s maneuvering capabilities ahead of future docking operations – whether with a lunar lander or a space station in lunar orbit.

After separating from the launch vehicle’s second stage, the spacecraft is expected to deploy five small satellites from countries that signed scientific cooperation agreements under the program. Among them are satellites from Germany, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea, selected to study the performance of certain electronic components, radiation shielding, navigation systems, and more. The satellites are expected to operate in a high orbit around Earth.

At the end of the high-apogee orbit—after about a day in space—and assuming the tests have gone smoothly, the spacecraft will ignite its own engine in the service module and enter a trajectory that will bring it to a close encounter with the Moon about four days later. As noted, it will not enter lunar orbit; instead, it will make a relatively close flyby, using the combined gravity of the Moon and Earth to bend its path back toward Earth through a lunar gravity assist. This kind of trajectory is known as a “free return,” meaning it sends the spacecraft back toward Earth without requiring a major engine burn or other large maneuvers—though a few small course corrections are likely on the way to the Moon.

The journey to the Moon will take about four days. At its most distant point, the spacecraft will pass roughly 6,500 kilometers beyond the Moon’s far side. The astronauts will see the Moon relatively close, but it will still appear only about the size of a basketball held half a meter from their eyes. A flyby that far beyond the Moon could put the crew into the record books as the humans who have traveled farthest from Earth—more than 400,000 kilometers. The exact peak distance will depend on launch timing, and a difference of a few thousand kilometers could determine whether they break the record or merely come close.

In coverage ahead of the mission, Artemis II is often compared to Apollo 8, the first flight in which humans traveled to the Moon to test propulsion, navigation, communications, and other systems before the lunar lander was ready. It was a groundbreaking mission, but the comparison is not entirely fair. Apollo 8 fired its engines to enter low lunar orbit, circled the Moon ten times at an altitude of about 100 kilometers, then fired again to depart lunar orbit and return to Earth—an operation far more complex and demanding, especially with late-1960s technology.

Artemis II’s profile is closer to what happened to Apollo 13. That mission was meant to land on the Moon, but an explosion on the way forced the crew onto a free-return trajectory in a race to get home safely. In the end, Apollo 13’s astronauts were the only humans to fly a path similar to Artemis II’s planned free return—and they are the ones who hold the distance record that may now be broken.

During the journey to the Moon, the crew’s daily schedule will be packed with spacecraft system tests, emergency drills, and evaluation of the spacecraft’s radiation shelter—an area lined with stowage cases where the astronauts are meant to huddle in the event of solar storms or elevated radiation levels. They will also carry out medical experiments, including measuring radiation exposure, tracking physiological indicators, assessing their physical and mental condition throughout the mission, and collecting and storing saliva and blood samples. The data collected will allow scientists to analyze the effects of microgravity and radiation—and of the crew’s overall condition—on the human body at the molecular level, with particular emphasis on the immune system.

As the crew approaches the Moon—and especially during the close pass—the astronauts will photograph and document it with cameras far more advanced than those available to earlier lunar crews, collecting material for geologists and astrophysicists as well as data intended to support later Artemis missions.

The flight trajectory and key phases of the Artemis II mission | Source: the Canadian Space Agency and NASA

Record Speed

The flyby past the Moon’s far side will bring a communications blackout with Earth lasting 30 to 50 minutes, depending on the spacecraft’s distance from the Moon. Once it emerges on the other side, the spacecraft will begin its journey back toward Earth, which will also take about four days. On the return trip—as on the way out—the astronauts will stay busy testing the spacecraft’s systems, their equipment, and their own performance. The crew is also expected to fire the spacecraft’s engines several times for small trajectory corrections.

About half an hour before splashdown, the service module will separate from the spacecraft and be sent onto a trajectory that ends with it burning up in the atmosphere. The crew module is expected to set a speed record, entering the atmosphere at roughly 40,000 km/h. Atmospheric friction will drive temperatures on the outside of the capsule to more than 1,600°C. Orion’s heat shield is ablative, broadly similar in principle to Apollo’s: it is made of special resins that heat up and glow during reentry, while small pieces of material gradually burn and flake away, carrying some of the heat with them. The plasma that forms around the capsule will also cause a communications blackout lasting several minutes.

After passing through the hottest phase of reentry, the spacecraft will deploy two drogue parachutes at an altitude of about 7.5 kilometers, slowing it to roughly 500 km/h. At about three kilometers, three small pilot parachutes will open, followed immediately by three main parachutes, each 35 meters in diameter. Together, they are designed to bring the capsule down for a controlled splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Southern California, hitting the water at about 25 km/h.

A simulated flight profile of the Artemis II mission.

Domestic and International Competition

From NASA’s perspective, the primary aim of Artemis II is systems testing: the first crewed launch of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, confirmation that the Orion spacecraft can safely carry astronauts on a lunar mission, and verification that key systems—life support, navigation, propulsion, communications, and more—perform as intended, including emergency hardware and procedures for handling malfunctions. Secondary objectives include gathering extensive data on spacecraft performance, crew health, and observations of the Moon.

Achieving those primary goals is expected to clear the way for the next Artemis missions—and, as NASA often emphasizes, to support eventual crewed missions to Mars as well.

The broader reality, however, is that it took NASA more than three years to move from an uncrewed flight to a crewed mission in the same spacecraft—even with a simpler flight profile—and there is little reason to expect the program to advance to the next stage any faster. For two of Artemis’s core elements—the launch rocket and the crew capsule—NASA has stuck with the traditional approach: contracting manufacturing to prime contractors and subcontractors such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing, while NASA integrates and operates the mission. The lunar lander, by contrast, is being developed under a different model, in which NASA is essentially purchasing a landing service from commercial providers. For the first Artemis landing missions, NASA selected SpaceX’s Starship as the lander, and for later missions it plans to use Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander.

As of now, nearly three years after Starship’s first launch and after 11 test flights, the vehicle has yet to reach orbit, demonstrate significant maneuvering in space, carry out in-space refueling, or achieve a fully successful landing on solid ground. All of these are essential milestones on the path to a crewed lunar landing—and, presumably, even after completing them, the company would still need to demonstrate an uncrewed landing on the Moon. At the current pace, it is hard to see that entire sequence being completed in less than three or four years.

NASA’s new administrator, Jared Isaacman, has hinted since taking office last month that the agency may broaden the competition and award the first landing to whichever lunar lander is ready in time. But development of Blue Origin’s lander has not been moving quickly either. A first version was delivered to NASA for testing last week, but it is a scaled-down, uncrewed model of the lander. Even if those tests go well, the crewed version would still need to clear the same major milestones—a process likely to take years. Meanwhile, Blue Origin’s heavy-lift rocket, New Glenn, has completed only two launches so far.

Even after a company completes the early demonstrations and delivers a lander to NASA, the agency will still need many months—if not years—to train crews to operate it and to develop, together with the contractor, detailed operating and safety procedures. Interfaces with NASA systems would also need to be finalized—from Orion itself to any future space station placed in lunar orbit. Some of this work can proceed in parallel with development, but not all of it.

And this is not only an internal U.S. competition. China has repeatedly stated its intention to land humans on the Moon in 2030. While it releases relatively few details, there is no doubt it is advancing quickly. In 2024, China completed the first-ever robotic collection of soil samples from the Moon’s far side, and this year it plans another robotic landing—bringing a rover and a rocket-powered drone—to the Moon’s south polar region.This is the most sought-after “real estate” on the Moon because permanently shadowed craters there may contain frozen water—water that could also be used to produce breathable oxygen and rocket propellant. In addition, the rim of Shackleton crater near the south pole is one of the few places on the Moon that receives near-continuous sunlight, while most of the lunar surface alternates between roughly two weeks of daylight and two weeks of freezing darkness—a cycle that makes long-duration operations difficult. China is also pressing ahead with development of its own lander, alongside steady progress on launch vehicles and the operation of a crewed space station.

Artemis II is a significant step toward returning humans to the Moon—but it is still an early step on a long, steep climb, with a strong and ambitious rival also moving toward the summit. The United States has formidable technological capabilities, but it may be that winning this race will require a shift in mindset: moving away from architectures built around legacy systems and channeling the billions into commercial development of an integrated launch-and-landing capability—before the world watches, live on television, China’s flag planted near the Moon’s south pole.