The Beginnings of Bipedalism: When Did We First Walk Upright?

Researchers have examined the bones of a seven-million-year-old ape and concluded that it walked on two legs. This new finding challenges earlier studies of the same fossils, which reached different conclusions.

20 January 2026

|

7 minutes

|

Towards the end of the 19th century, Dutch researcher Eugene Dubois traveled to Indonesia to search for fossils of early hominin species. He was fortunate to discover a skull fragment that belonged to an ancient hominin, and later also found a thigh bone. These fossils were eventually dated to between 700,000 and 1 million years ago.

The thigh bone especially intrigued researchers because it closely resembled our own thigh bone and clearly suggested that its owner walked upright. At the time, the prevailing assumption was that bipedalism – a trait characteristic of humans but not seen in other apes or hominids – evolved relatively late in our evolutionary history. Therefore, the discovery that the species from Indonesia also walked on two legs was both surprising and significant. So much so that Dubois named the species he discovered Pithecanthropus erectus (Erect Ape-man), believing that this defining characteristic would set it apart from other species. He was mistaken.

Recent findings from the past few decades, including fossil bones and footprints, have shown that upright walking developed millions of years earlier, well before the time of the Indonesian fossil. This fossil has since been reclassified into our genus, Homo, but it still retains its distinction for upright posture and is classified as Homo erectus. The human and chimpanzee lineages diverged around 6-8 million years ago, and it appears that species in our lineage began to walk upright shortly after that.

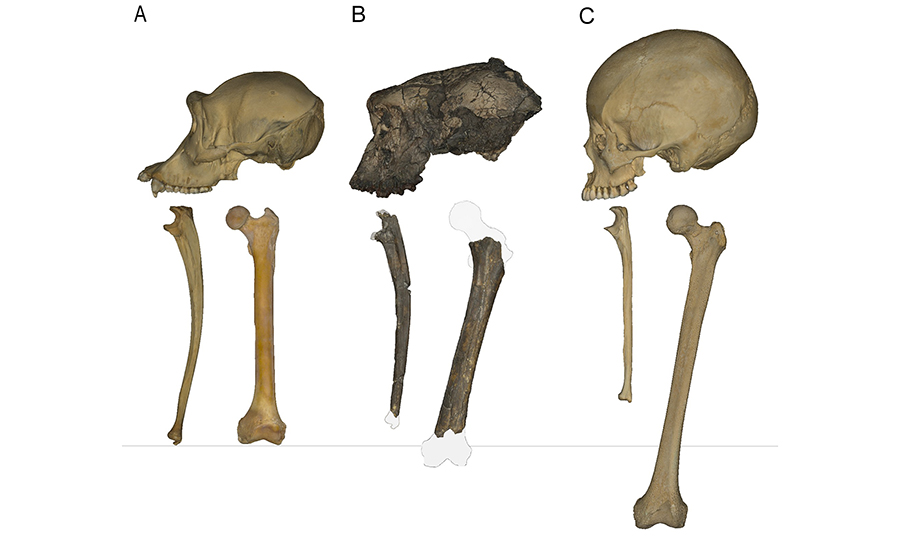

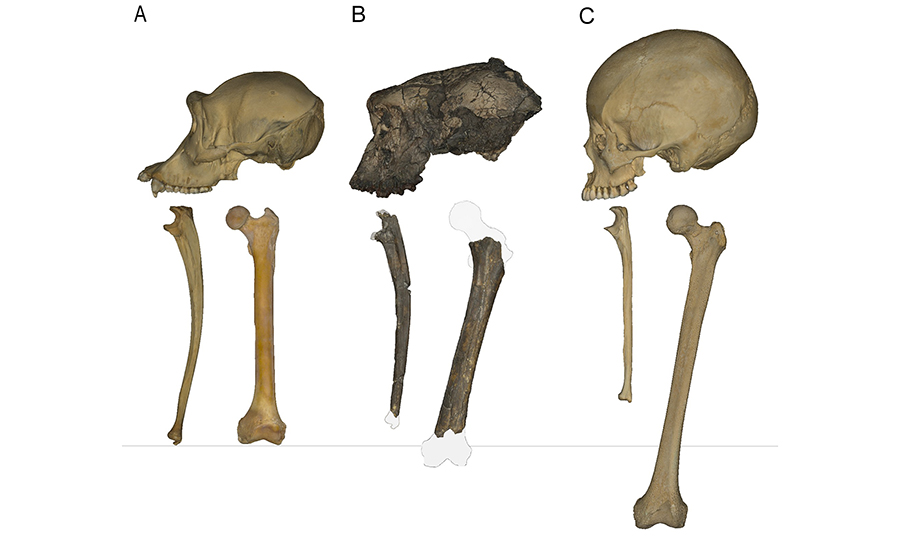

Cranium (skull), ulna (forearm), and femur (thigh bone) of chimpanzee (P. troglodytes) (A), Sahelanthropus tchadensis (B), and human (H. sapiens) (C) (from left to right) | Scott Williams/NYU and Jason Heaton/University of Alabama Birmingham.

So, when did it all begin? The answer may lie in a fossil approximately seven million years old, discovered 25 years ago in Chad, Africa. The fossil was named Sahelanthropus tchadensis: the genus name means “Sahel ape-man,” referring to the region in Africa where it was found, and the species name refers to Chad, the country of discovery. It was later nicknamed Toumai, meaning “hope of life” in the local language. As expected from such an ancient fossil, it doesn’t include a complete skeleton but rather part of a skull, several jawbone fragments, teeth, as well as a thigh bone (femur) and parts of two forearm bones—the ulna (the bone between the elbow and wrist) and the radius.

The thigh and forearm bones were examined by several research groups, leading to differing conclusions. Some believe that the bones suggest Sahelanthropus belonged to our lineage and walked on two legs at least part of the time. Others argue that the bones are more similar to those of a chimpanzee, indicating quadrupedalism.

Now, the latest (so far) paper in the ongoing saga of the Chad fossil has been published. The researchers claim that a new analysis of the bones provides evidence that Sahelanthropus did indeed walk upright, on two legs. If true, this would mean that bipedal walking, once thought to be unique to humans, began as early as seven million years ago.

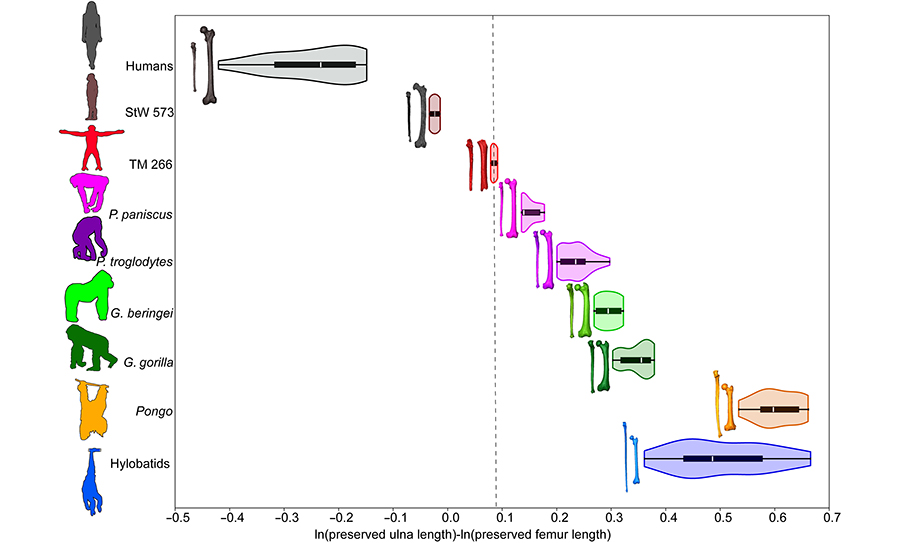

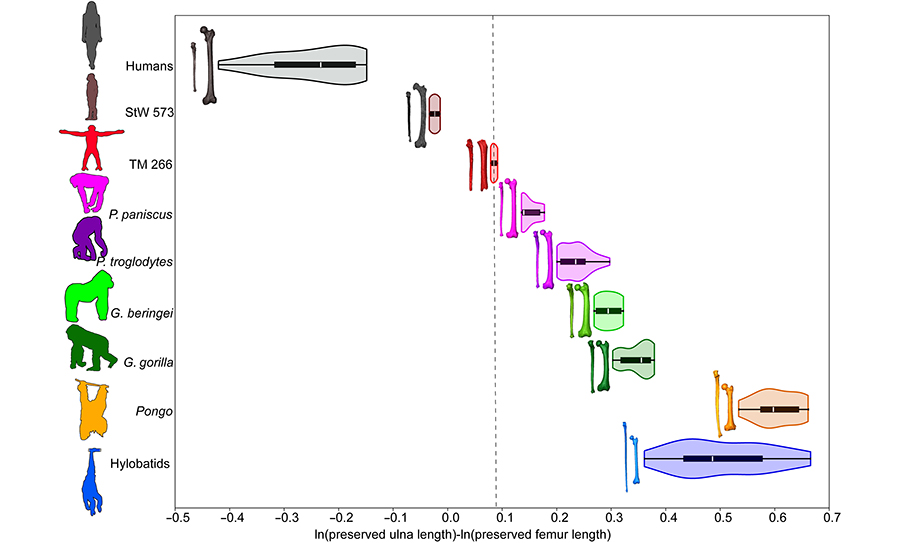

The logarithmic ratio of the length of the ulna (forearm bone) to the femur (thigh bone). The dashed line shows that Sahelanthropus is positioned between a bonobo and an early hominin, indicating limb proportions intermediate between those of an ape and a human. | From Williams et al., 2026.

The Bone of Contention

When the leg and arm bones were first discovered in 2001, researchers collected them along with other nearby findings, but initially did not realize they might belong to the same animal. It was only after further examination that the bones were identified as hominid. Since no other fossils from the same family had been found in the area, it was concluded that they likely belonged to Sahelanthropus.

In 2020, researchers from France and other countries examined the bones and concluded that Sahelanthropus walked on four legs, not two. However, in 2022, a different group of researchers published a paper reaching the opposite conclusion. They argued that the thigh bone more closely resembled those of early human species rather than great apes. They also examined the internal structure of the bone, which, in their view, suggested it could bear significant weight – similar to the thigh bone of bipeds.

In 2024, the first group published a response paper, attempting to refute the 2022 paper’s claims and arguing that the thigh bone more closely resembled those of a great ape.

The latest paper, written by researchers from the United States, presents further analysis of the bones. Their conclusion is that Sahelanthropus walked on two legs at least part of the time, supported by several distinct characteristics of the thigh bone.

The first characteristic is the rotation of the lower part of the thigh bone compared to the upper part. This rotation is present in humans but not in modern great apes. It helps position the knees and ankles closer to the body’s center of mass, supporting bipedal walking.

The second characteristic is the arrangement of pelvic muscle markings on the thigh bone. Bipeds have strong pelvic muscles arranged differently than quadrupeds, adapted to support an upright posture. According to the researchers, the markings on the Sahelanthropus thigh bone resemble those of bipeds, indicating that they likely served as attachment points for anchoring muscles that facilitate bipedal walking.

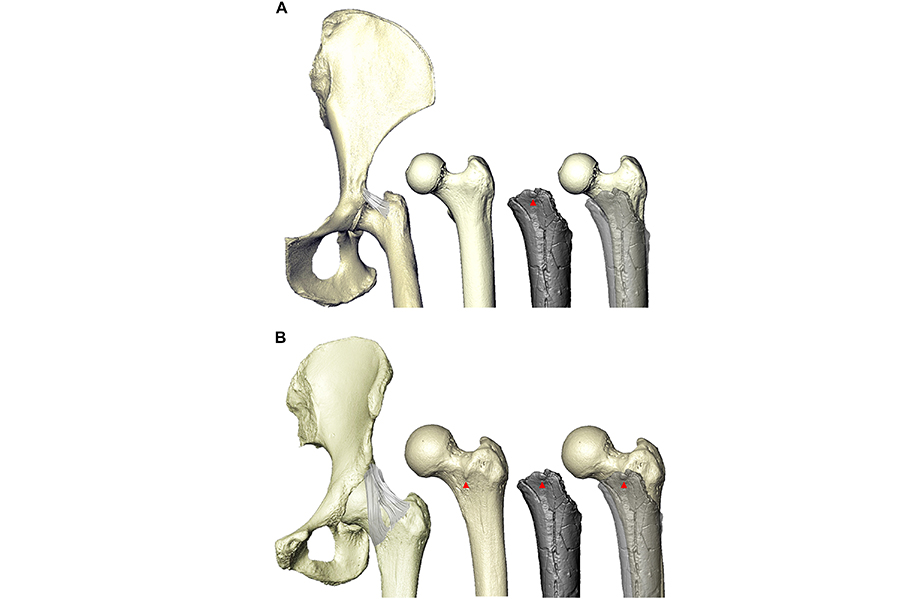

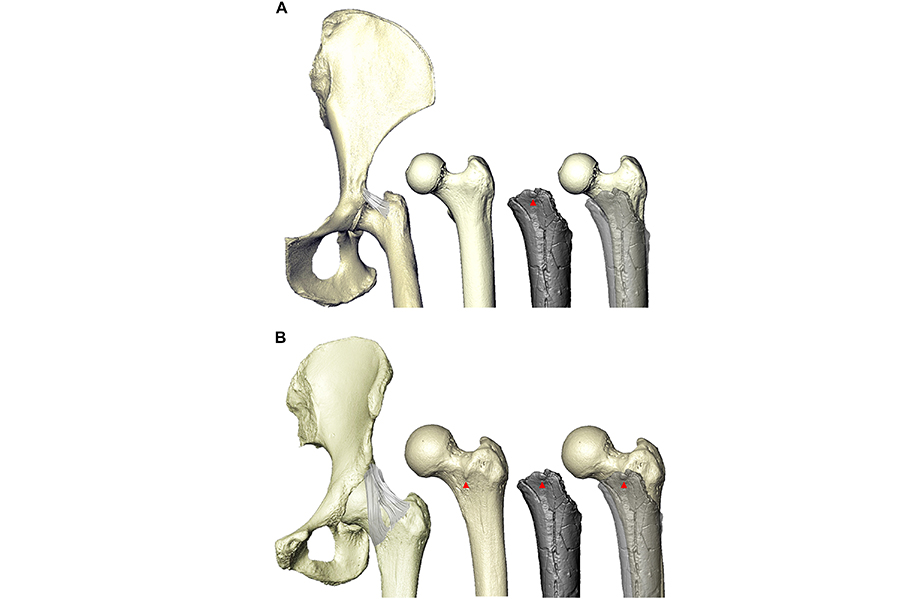

However, both of these characteristics had already been noted in previous studies. The new finding in the current paper is the identification of a small bump at the top of the thigh bone. This bump is connected to the iliofemoral ligament, the strongest ligament in the human body, which links the thigh to the pelvis. In bipedal walking, this ligament helps stabilize upright posture and prevent falling. So far, this bump, which attaches the ligament, has only been found in bipeds. Its presence in Sahelanthropus strongly supports the hypothesis that it too walked on two legs.

Comparison of thigh bone structures between a chimpanzee (light bone, second from left) and Sahelanthropus tchadensis (shown in gray and lighter gray overlaid on the human) (A), and between a human (light bone, second from left) and Sahelanthropus tchadensis (shown in gray and lighter gray overlaid on the human) (B). The small bump on the thigh bone (indicated by the arrow), where the iliofemoral ligament attaches, is present in both the human and Sahelanthropus thigh bones but absent in the chimpanzee thigh bone. | From Williams et al., 2026.

Leg vs. Arm: Clues from the Limb Ratio

The researchers also compared the thigh bone to the forearm bone to estimate the relative length of the leg and arm. Great apes have relatively short legs and long arms, which help them climb trees and hang from branches, whereas humans have longer legs, aiding in efficient walking. The ratio of leg to arm length in Sahelanthropus was found to be between that of great apes and humans, meaning it had shorter legs than ours but longer than those of a chimpanzee. This limb ratio is closer to that found in Australopithecus, a later species in the human lineage known to walk on two legs.

“Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees, foraging and seeking safety,” summarized Scott Williams, from New York University’s Department of Anthropology, who led the study, in a press release. “Our analysis of these fossils offers direct evidence that Sahelanthropus tchadensis could walk on two legs, demonstrating that bipedalism evolved early in our lineage.“

Will this paper settle the debate? It’s still uncertain. We’ll need to wait for responses from the other researchers who analyzed the bones, as well as from other fossil experts. It’s possible that only future discoveries of additional fossils will provide the definitive answer to when our ancestors first stood upright and began walking on two legs.