Lessons from Ukraine’s Holodomor: Famine and Diabetes

An analysis of data from the Great Famine of the 1930s shows that children whose mothers experienced malnutrition during early pregnancy were more likely to develop diabetes later in life

The human race has endured severe periods of famine throughout history, but these crises came at a heavy cost—disease, suffering and death. The World Health Organization estimates that even today more than 800 million people around the globe suffer from hunger, many of whom will carry its physical consequences for the rest of their lives.

Yet our ability to investigate the physiological effects of hunger in depth remains limited. Ethical constraints make it impossible to conduct controlled experiments in which participants would be intentionally starved. As a result, the reliable evidence we have on the long-term impacts of hunger comes from only a small number of studies, only a handful of which were interventional experiments capable of demonstrating causality.

Most research in this field relies on observational data – either collected at the time or reconstructed later—on groups of people who experienced starvation under various circumstances, including concentration-camp survivors, prisoners of war, and hunger strikers. Researchers occasionally benefit from “natural experiments,” situations in which life circumstances inadvertently create conditions resembling a controlled study—conditions that would be impossible, and unethical, to engineer deliberately. For instance, some studies have looked back at the long-term health of shipwreck survivors who endured days with almost no food, comparing them with individuals who led similar lives but never faced such extreme deprivation.

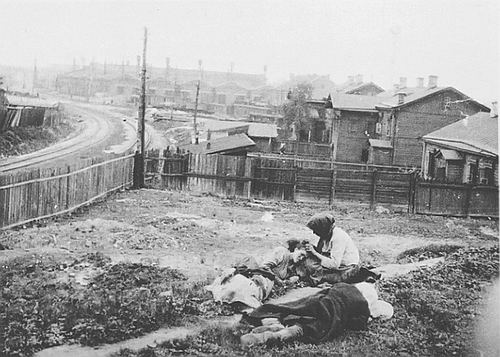

The short-term effects of acute hunger are well documented, including a significant rise in mortality relative to normal death rates (excess mortality). Over longer periods, research has shown that people who experienced hunger in childhood were more likely to develop kidney-function problems as adults. In contrast, no consistent evidence has emerged so far linking extreme food deprivation in the earliest stages of life to higher rates of cardiovascular disease or diabetes in adulthood. Recently, however, an international study revisited data from several decades ago to reassess the potential impact of hunger during pregnancy on the development of diabetes later in life.

An international study revisited data from several decades ago to examine the possible effects of hunger during pregnancy on the development of diabetes later in life. A nurse checks a patient’s blood sugar level | Shutterstock, Dorde Krstic

The Holodomor: Ukraine’s Great Famine

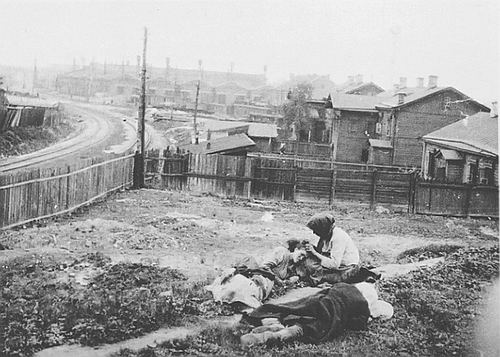

In 1932–33, the Soviet Union imposed a deliberate and devastating policy of agricultural collectivization on its most fertile farming regions, chief among them Ukraine. As part of this policy, the communist regime seized most of the farmers’ harvests, leaving them with meager food rations that were nowhere near enough to sustain life. The result was a catastrophic famine in rural Ukraine, claiming the lives of millions. The exact death toll remains unknown.

The researchers analyzed data on more than ten million children born in Ukraine between 1930 and 1938—some just before the Great Famine began and others in the years that followed. They classified the newborns into four groups based on the severity of famine conditions in their birth region, ranging from areas that escaped hunger entirely to those where excess mortality rates signaled extreme starvation. These records were then cross-referenced with health data from the early 2000s on roughly 120,000 people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes—a disease marked by the body’s reduced ability to absorb sugar from the bloodstream.

The researchers found that individuals who experienced hunger early in life—at any level—faced a higher risk of developing diabetes compared with those who did not. Moreover, the more severe the famine, the greater the likelihood of developing diabetes later in adulthood. In fact, people born in the regions hardest hit by the famine were almost 2.5 times more likely than those from unaffected areas to develop diabetes as adults.

These findings apply to everyone born around the time of the Great Famine in Ukraine. But the researchers also asked a more nuanced question: does a child’s exact age during the famine affect their later risk of diabetes? To examine this, they carried out an additional statistical analysis (a sensitivity analysis), cross-referencing each person’s birth year with the timing of the famine’s peak. They found that only individuals who were in the first trimester of fetal development when the famine was most severe showed a marked increase in diabetes risk later in life. Infants who had already been born, as well as fetuses in the second or third trimester at the height of the famine, did not exhibit the same pattern. This suggests that early pregnancy is indeed a particularly sensitive biological window.

Severe famine in rural Ukraine claimed the lives of millions. Photo from the famine in Ukraine, 1922–1923 | Wikimedia, Alexander Wienerberger

What Explains the Connection?

Although the study did indeed find a link between hunger and the development of diabetes later in life, its findings are not sufficient to prove causality—that is, to show that hunger during fetal development is itself the factor causing the disease, and that no other independent variable explains the association. First, although the sample size is large, it is geographically limited. Dietary patterns and environmental conditions vary significantly from place to place and from country to country, so periods of famine in other parts of the world could potentially lead to different long-term health outcomes for survivors.

In addition, the researchers’ choice to assess famine severity on the basis of excess mortality rates is not self-evident. It is possible that at least a substantial portion of the excess mortality may be attributable to factors only indirectly related to hunger—or not related to hunger at all—such as the spread of infectious diseases, poor hygiene, or the lack of medical supplies and health services. Any of these factors could also have influenced fetal development. Likewise, some of the socioeconomic characteristics of the populations living in the regions examined may have changed dramatically over the decades—for example, due to large-scale migration—and such changes may also affect diabetes risk. Finally, because type 2 diabetes is strongly influenced by obesity and lifestyle, the lack of detailed analysis of participants’ weight trajectories, physical activity, and dietary habits represents a significant limitation of the study.

Despite these caveats, there are good reasons to believe that the observed connection may indeed be causal. The starvation imposed on the rural population of Ukraine was sudden and stemmed from an external political decision, giving the situation characteristics similar to those of a natural experiment. The fact that the effect appeared only among individuals who experienced hunger at the beginning of pregnancy, and was especially pronounced in regions where the famine was most severe—meaning it depended both on timing and on intensity—strengthens the likelihood that the association reflects a genuine causal mechanism rather than a coincidental correlation.

The study opens a new research direction that may illuminate how deficiencies in specific nutrients during critical developmental windows contribute to the emergence of metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, in adulthood. Such a mechanism could help explain why the consumption of ultra-processed foods has been associated with an increased risk of developing diabetes later in life, whereas a healthy and varied diet reduces diabetes risk even among people who are overweight. Identifying the particular substances or pathways involved could eventually lead to the development of preventive treatments for pregnant women, helping protect their children from developing diabetes as adults

In addition, the researchers raise the possibility that the observed association may arise from selective survival of fetuses during periods of famine. In other words, there may be some physiological mechanism that enhances fetal survival under hunger-related stress, and that same mechanism may also predispose those survivors to an increased likelihood of developing diabetes later in life.