The Bleached Future of Coral Reefs: Nearing a Tipping Point

An unprecedented wave of coral bleaching driven by warming oceans may signal that one of the world’s most important ecosystems has already reached a point of no return.

17 January 2026

|

6 minutes

|

Beneath the ocean’s surface, along ocean coastlines around the world, a global ecological crisis is unfolding. Vast coral populations are bleaching and declining, some of them irreversibly. This occurs when corals lose the symbiotic algae that live inside them, provide them with much of their energy, and give them their vivid colors. Over the past two years, an unprecedented bleaching event has been recorded across coral habitats throughout the oceans, including the bleaching of entire reef systems. This is the fourth – and deadliest – global event since the phenomenon was first documented.

According to data from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a 2025 report by the Global Tipping Points research community, many coral reefs have already crossed their heat-tolerance thresholds and may have lost the ability to recover even if sea-surface temperatures decline again. This is not only a cry for help from the depths, but a clear warning sign about the state of the climate system and the ecosystem as a whole.

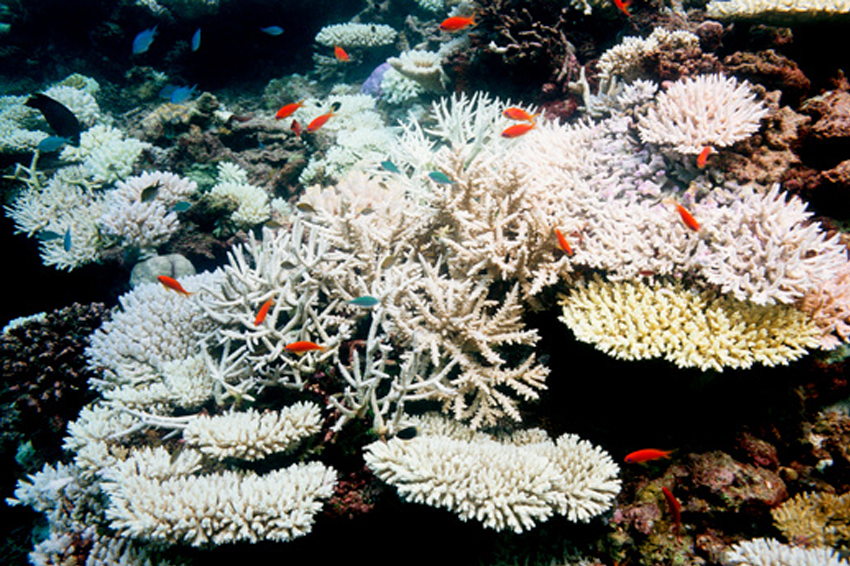

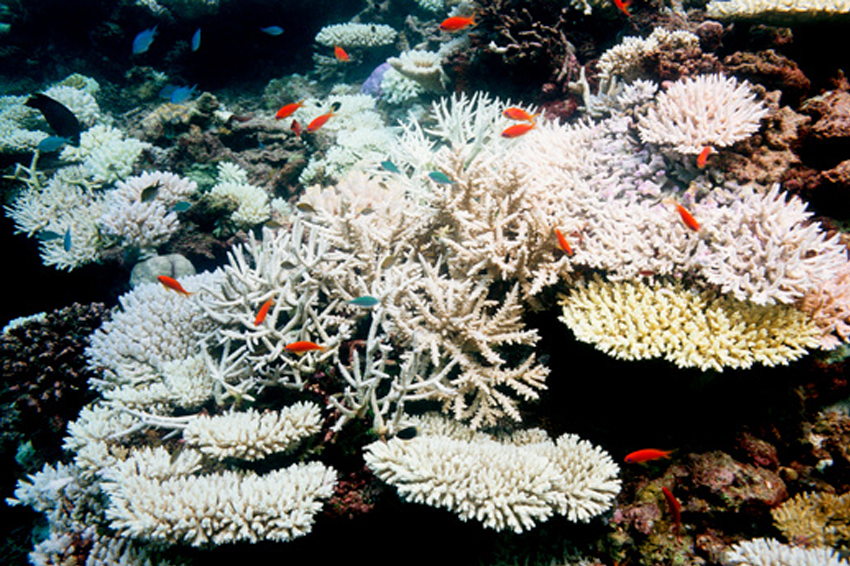

An unprecedented bleaching event across coral habitats worldwide, including the bleaching of entire reef systems. Bleached corals off the coast of the Maldives | Georgette Douwma / Science Photo Library

When the Sea Gets Too Warm

Corals are tiny marine organisms in the phylum Cnidaria and live in enormous colonies, building reef structures from limestone. A healthy coral reef resembles a vibrant underwater city—a bustling, colorful world of calcium carbonate formations in a variety of shapes, from branching structures to domes and tiny arches. Reefs cover less than one percent of the seafloor, yet their ecological and economic importance is immense. They provide habitat for about a quarter of all marine species, supply food for roughly half a billion people, and support economies that depend on fishing and marine tourism.

This rich ecosystem relies, among other things, on a delicate partnership between corals in shallow waters and microscopic algae called zooxanthellae that live within their tissues. The algae capture sunlight and carry out photosynthesis—a process in which they use solar energy to produce sugar molecules. Some of these sugars are passed to the coral, which uses them to generate the energy it needs to build its skeleton and sustain its day-to-day activity. In return, the algae benefit from a protected environment and feed on substances the coral releases. This partnership, known as mutualistic symbiosis, gives corals their vivid colors and enables them to remain relatively resilient to changes in environmental conditions.

However, when seawater temperatures rise above a certain threshold, the algae begin releasing harmful compounds that endanger the coral. In response, the coral expels the algae—its primary source of energy—and without them it turns white. Sometimes, an increase of just one or two degrees Celsius above the local long-term average temperature is enough to disrupt this delicate partnership.

Coral bleaching is not just about color. The loss of color is merely the most visible sign of deeper damage to the entire reef ecosystem. When corals lose their algae, they weaken, and their ability to build the limestone skeletons that make up the reef is impaired—disrupting the reef’s overall structure. As a result, habitats, shelters, and breeding grounds gradually shrink for fish and many other animals that depend on the reef.

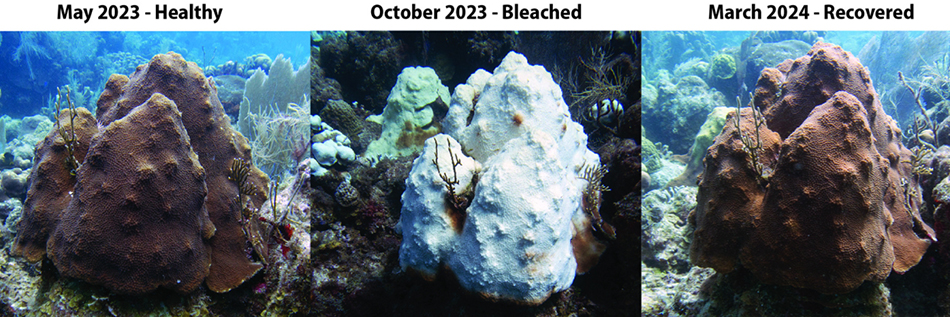

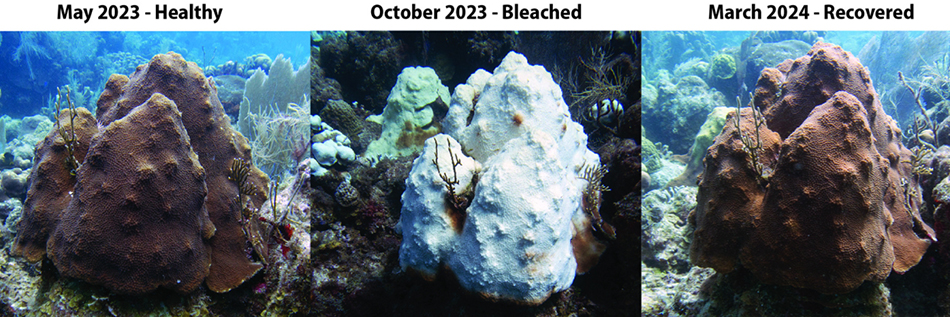

Even when corals survive bleaching, the road to recovery is long. The recovery process can take years, and during that time corals are particularly vulnerable to starvation and disease. A major threat comes from the spread of larger algae that grow on the reef’s surface rather than inside the coral; these algae compete with corals for space and light, making recovery more difficult. As heat waves become more frequent, corals’ ability to recover is further compromised, and in some cases reefs fail to recover at all.

Bleaching at Record Pace

Since the 1980s, three global coral bleaching events have been documented. In 2023, an unusual sequence of marine heatwaves began—an episode the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) describes as the fourth and most severe bleaching event since measurements began, and the second within a decade. The event is affecting nearly all coral reefs worldwide, and at some sites severe bleaching has been reported alongside coral mortality of up to 90 percent—an unprecedented rate, even compared with previous events.

Even the coral reef of Eilat – at the northern tip of the Red Sea—a naturally warm region where reefs have until now been considered relatively resilient to heat stress—did not remain immune. In the current event, unusual bleaching was documented there as well—a reminder that even systems thought to be stable can be pushed to the breaking point when heat persists.

Even when corals survive bleaching, the road to recovery is long. A boulder coral (Orbicella annularis) in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands: from a healthy state (May 2023), through bleaching due to extreme heat stress in the Caribbean basin (October 2023), to recovery (March 2024) | NOAA

The Thermal Point of No Return

The Global Tipping Points report also finds that some of the world’s coral reefs may already have crossed a temperature “point of no return,” also described as a “thermal tipping point,” at roughly 1.2°C above the average level in pre-industrial times. Beyond this threshold, the system’s ability to recover is severely compromised. According to the report’s authors, this is the first domain in which humanity has effectively crossed a climate tipping point – when gradual change pushes an ecosystem past a threshold, leading to a profound and possibly irreversible shift.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasts that by the middle of this century, bleaching events could become so frequent that most of the world’s reefs will experience them almost every year. Even under an optimistic scenario in which the rise in global average temperature is halted at about 1.5°C – the target set by the Paris Agreement – nearly all coral reefs are expected to lose many of their ecological functions. The Global Tipping Points report adds that the only way for some reefs to continue functioning normally would be for the global average temperature to fall back below the 1.2°C threshold above pre-industrial levels—and that an even larger drop may be required, perhaps to around 1°C.

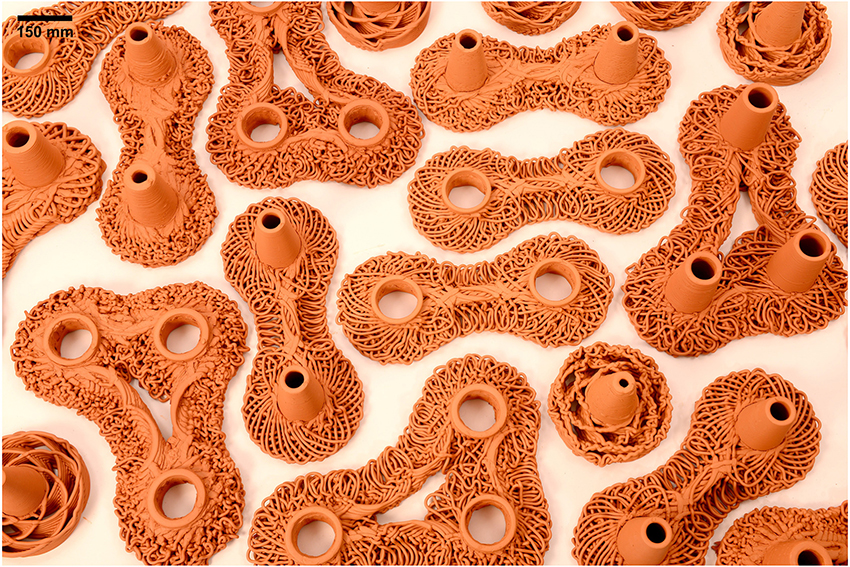

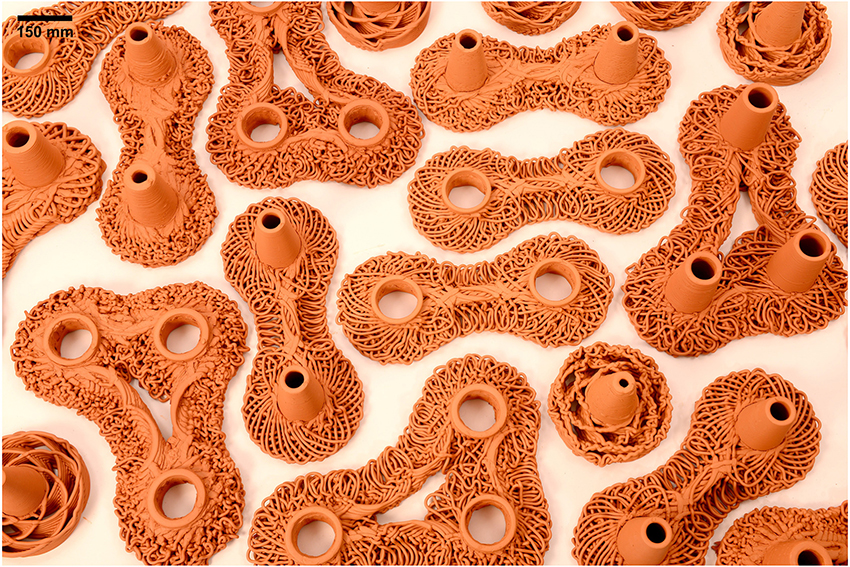

Among the methods currently being explored are the cultivation of artificial corals and the development of materials that replicate the skeletal structure of coral limestone formations. A ceramic artificial coral reef developed by Israeli researchers | From the paper Berman et al., 2025

A Climate Domino Effect

Researchers regard coral reefs, rainforests, and glaciers as three key natural Earth’s climate systems, which are interconnected by feedback loops. Damage to one can trigger a cascade of changes that increase the vulnerability of the other systems and undermine the stability of the climate system as a whole. When several such systems are disrupted at the same time, they push the global climate to warm at an accelerated pace. This is described as the climate domino effect.

Coral reefs absorb carbon dioxide and help stabilize marine ecosystems; the Amazon rainforest acts as a “green lung,” taking up carbon dioxide; and glaciers cool the planet by reflecting sunlight back into space. When reefs degrade, forests are cut or burned, and glaciers melt, each of these protective mechanisms weakens – and their combined impact drives the climate system toward faster and even more dangerous warming.

Many efforts are now underway to slow the crisis. Researchers around the world are developing tools to restore coral reefs and improve their heat resilience. Approaches being tested include cultivating engineered or lab-grown corals that can better withstand higher temperatures, and developing materials that mimic the skeletal structure of coral limestone formations. This research shows that the struggle for the future of reefs is not merely a story about losing color; it is about the need to halt a destructive process before the bleaching below the surface begins to fade the world above it as well.

The fate of coral reefs is not yet sealed. Cutting greenhouse-gas emissions, curbing overfishing, and protecting areas where reefs still function are necessary to slow the collapse and give reefs a chance to recover from the current crisis. But these steps alone will not be enough. Alongside determined global political and public action, a sustained scientific effort is needed to explore ways to strengthen reefs’ resilience to the destructive forces threatening them—and to help them adapt to a warming world.