Do Tattoos Increase Cancer Risk?

A twin study suggests that people with tattoos may face a higher risk of skin cancer and lymphoma than those without tattoos.

8 January 2026

|

5 minutes

|

Clear, compelling evidence of tattooing—permanently marking the skin by inserting pigments into the dermis, the skin’s middle layer, using punctures or small cuts—has been found on mummified bodies dated to the third millennium BCE. Similar findings, including those on “Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman,” indicate that the practice of tattooing was widespread across different regions of the world.

The decision to get a tattoo can reflect many different motivations. In many peoples and cultures, tattooing is a longstanding tradition. Recent studies also show that in Western countries such as the United States, tattoos have become a common and highly popular form of self-expression, especially among young people. In recent years, for example, religious texts and images have increasingly been used to adorn the body in the form of tattoos.

As tattoos become more widespread, however, important questions are being raised about the safety of tattooing and exposure to tattoo inks. One major concern is the lack of large-scale epidemiological studies examining whether components of tattoo ink may contribute to cancer risk.

In many peoples and cultures tattooing is a tradition. Tattoos on the back of a Buddhist monk | PiercarloAbate, Shutterstock

Black Ink

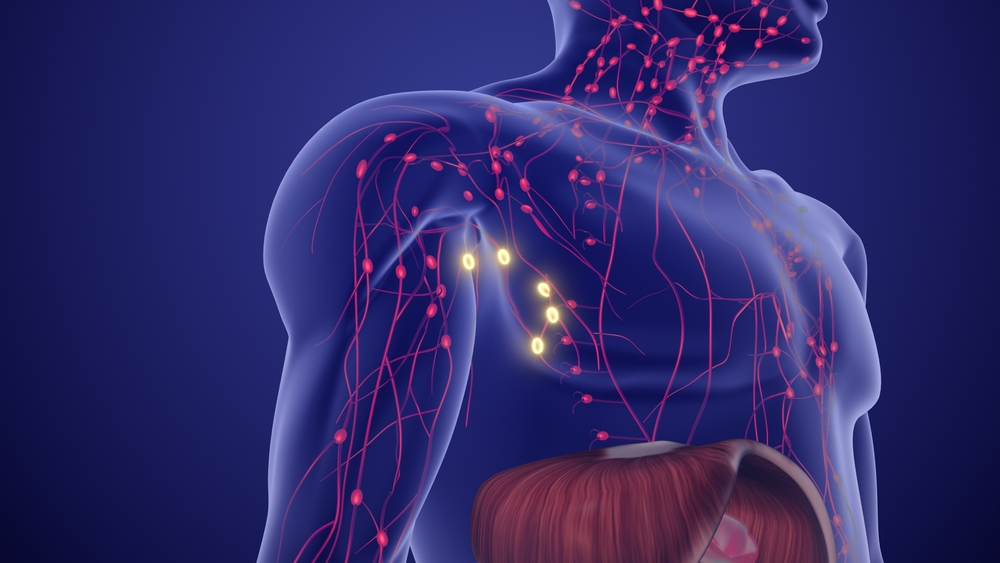

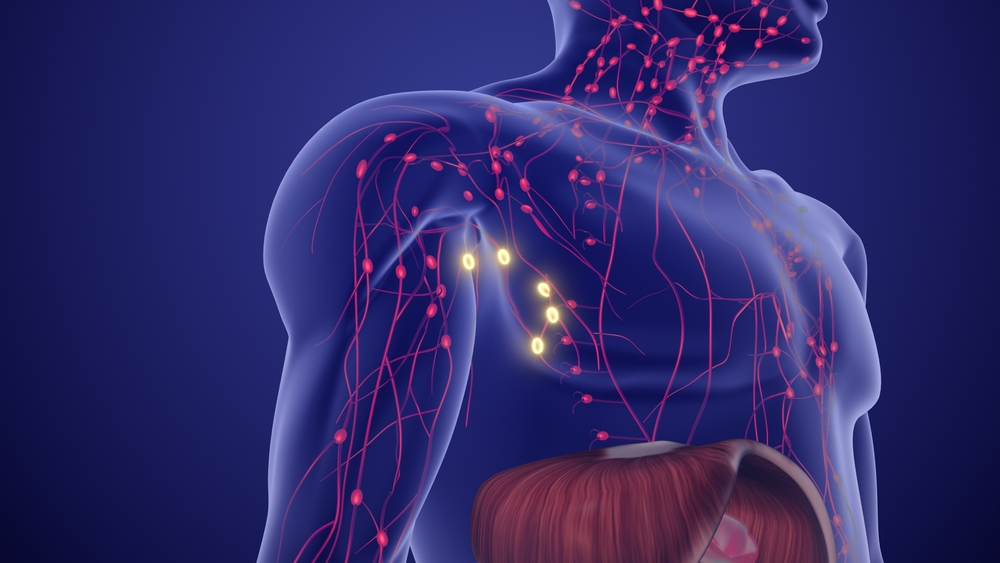

Studies suggest that particles from tattoo ink can accumulate in nearby lymph nodes, and there is evidence that they may also migrate through the bloodstream to other internal organs. Whether these particles are harmful—to the skin, the immune system, or internal organs—remains an open question, and further research is needed to understand the full range of their potential effects.

Black tattoo ink commonly contains soot and substances such as carbon black—a powder of tiny carbon particles that, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), may be carcinogenic to humans. However, this classification is based primarily on studies examining respiratory exposure to carbon black and its possible link to lung cancer. Because tattooing involves skin exposure rather than inhalation, these findings cannot be used to infer a connection between carbon-black tattoos and cancer.

A major challenge in studying potential links between tattoos and cancer is that many cancers develop after a long latency period, making it difficult to identify specific causes—especially when individuals are also exposed to other environmental risk factors. Given the limited and uncertain evidence, several researchers and health organizations have called for large-scale epidemiological studies to examine whether tattoo ink exposure is associated with higher risks of certain cancers, such as lymphoma—a group of cancers of the lymphatic system—as well as skin cancer. A large Swedish study on lymphoma published in 2024 reported a possible association between tattoos and an increased risk of the disease, but further research is needed to establish causality.

The black ink commonly used for tattoos contains soot and substances such as carbon black. Tattoo machine and ink | Mikhail_Kayl, Shutterstock

The Danish Twin Study

In 2021, the Danish Twin Tattoo and Cancer Cohort (DTTC) was established to collect research data from twin pairs—both cases in which one twin is ill and the other is not, and a broader comparison group of individuals who share a common characteristic and are followed over time. Comparing twins helps researchers distinguish between hereditary and environmental factors in cancer. The study analyzed subsamples drawn from the cohort’s database. Data were collected using a questionnaire that focused on tattoo-ink exposure among twins in Denmark.

The 5,900 twin pairs included in the cohort were identified by linking Denmark’s National Twin Registry with the National Cancer Registry. The researchers then looked for participants with predefined cancer types, guided by the hypothesis that tattoo ink can accumulate in particular parts of the body. Accordingly, they focused on cancers in tissues where ink is known to accumulate—such as the skin and lymph nodes—as well as internal organs that ink particles may reach via the bloodstream. Both analyses—the co-twin comparison (affected twin versus healthy co-twin) and the broader cohort comparison—examined adults who developed cancer and together included about 2,500 twin pairs.

In 2025, the researchers reported that, after accounting for age, age at tattooing, and follow-up duration, individuals with tattoos had about a 60% higher risk of developing skin cancer than those without tattoos. For tattoos larger than the size of a palm, the reported risk increase was about 140% for skin cancer and about 170% for lymphoma. In the broader comparison analysis, the reported associations were even stronger: tattooed individuals had about a 290% higher risk of developing skin cancer and about a 180% higher risk of developing basal cell carcinoma, one of the most common forms of skin cancer.

These findings are consistent with earlier reports documenting cases of squamous cell carcinoma, benign tumors, lymphatic system disorders, and even rare cases of malignant tumors that developed in tattooed areas.

When tattoos are larger than the size of a palm, the risk of developing lymphoma increases by about 170%. Lymph nodes | JitendraJadhav, Shutterstock

Limitations of the Study

Although the study aimed to examine routine decorative tattoos, the questionnaire did not distinguish between tattoo types. As a result, the sample likely included individuals with permanent makeup or medical tattoos, even though these differ substantially from decorative tattoos in typical ink composition, application methods, and size.

A further limitation concerns smoking, a well-established cancer risk factor that should be carefully controlled. The researchers relied on a relatively broad measure: participants were asked at what age they began smoking, and the analysis assumed they did not quit. This limited the study’s ability to account for changes in smoking behavior over time and may have affected the validity of the findings to some extent

Another major challenge is the absence of data on sun exposure—an essential variable when evaluating skin cancer risk. The researchers acknowledge the potential for bias here, though its direction is uncertain. A recent study examining non-European populations reported that people with tattoos may have higher sun exposure, but also use sunscreen more frequently. This underscores the complexity of tattoo-related behaviors and the importance of measuring them accurately when assessing potential cancer risks.

Another point raised by the researchers is that the observed association between tattoos and skin cancer may not stem from the ink itself, but from the fact that tattoos can conceal skin lesions, leading to delayed detection. In other words, the ink may not cause cancer, but it may make early detection more difficult, potentially resulting in diagnosis at a more advanced stage.

The study points to a potentially concerning association between tattoos and certain cancers, particularly among individuals with large tattoos. However, key limitations—including the absence of data on sun exposure, ink type, and smoking behavior—make it difficult to determine whether this relationship is causal or driven by bias, such as delayed detection of lesions obscured by tattoos. As a result, while the findings do not demonstrate definite harm, they highlight the need for caution and greater awareness among both the public and healthcare professionals. Further research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn. Tattoos may appear to be a purely aesthetic choice, but they may carry health risks that are not yet fully understood.