Moon Promises and Planet Births: Space News Roundup

NASA’s new chief promises to land humans on the Moon within three years; mice that returned from space have produced healthy offspring; European Space Agency’s computer systems have been breached; and rare documentation of planet formation. Space Highlights.

5 January 2026

|

7 minutes

|

A Promising Appointment

NASA’s new chief says the United States will return to the Moon within three years. Jared Isaacman, appointed about several weeks ago to lead the U.S. space agency, told CNBC in an interview that this would be achieved during President Trump’s second term, which is scheduled to end in January 2029.

The Artemis program—designed to return humans to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo program, began in 2022 with the Artemis I mission, an uncrewed Orion flight that passed close to the Moon. Artemis II is expected to send four astronauts into lunar orbit without landing, and NASA said a few months ago that the mission could launch as early as this coming February. Isaacman said it would take place “in the very near future,” without committing to a specific date.

Under NASA’s previous official plans, the first crewed lunar landing of this millennium is slated for 2027. Artemis III is planned to carry astronauts to lunar orbit aboard the Orion spacecraft, where they are expected to transfer to a SpaceX-built lunar lander derived from Starship. The plan depends on multiple in-space refueling operations involving Starship vehicles, and it is already apparent that the 2027 target is unlikely to hold. To date, Starship has not orbited Earth, has not completed the kind of controlled landing on Earth it would need to replicate on the Moon, has not demonstrated in-space refueling, and has not flown humans. Under these circumstances, even a landing by early 2029 would be a major challenge, requiring substantial effort and significant financial investment.

Blue Origin is also developing its own lunar lander, which is intended to serve NASA in later stages of the Artemis program, and it too will be based on in-space refueling capabilities. “That [in-space refueling] is what is going to enable us to go to and from the Moon affordably, with great frequency, and set up for missions to Mars and beyond,” Isaacman said in the interview – his first since taking office. He added that Trump’s renewed commitment to lunar exploration is key to establishing an orbital economy. “We’ve got to return to the Moon, establish an enduring presence, and realize the scientific, economic, and national security value,” he added.

On the economic front, Isaacman pointed to opportunities such as establishing data centers on the Moon and mining Helium-3 (³He) – an isotope rare on Earth but more abundant on the Moon, and potentially useful if controlled fusion can be developed as an energy source, though there is debate over whether mining it would be economically viable. He added that once a lunar base is established, the agency would consider investments in nuclear power on the Moon and nuclear propulsion for spacecraft in order to push exploration farther afield.

Planning to land humans on the Moon within the next three years. Isaacman at his confirmation hearing before the Senate committee on his appointment | Photo: NASA / Bill Ingalls

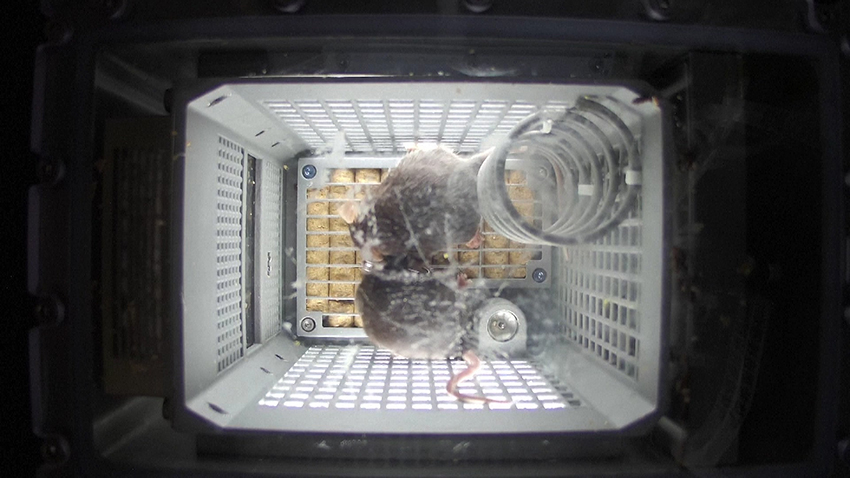

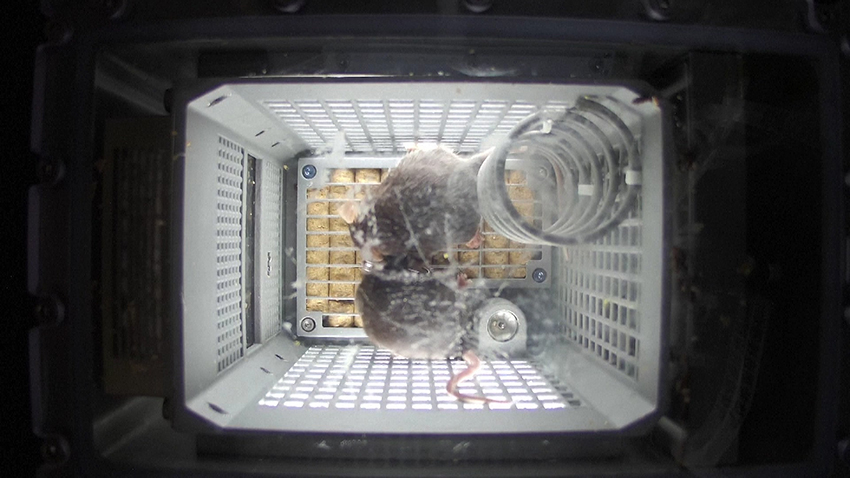

Fertile After Spaceflight

A female mouse that returned to Earth after about three weeks in space gave birth to healthy pups, suggesting that exposure to microgravity did not impair her fertility. Four mice—two males and two females—arrived at China’s space station in October 2025 with the Shenzhou 21 crew and returned to Earth in November with the Shenzhou 20 crew, whose return was delayed after a crack was discovered in the spacecraft’s window. On December 10, one of the female mice delivered a litter of nine pups. Six survived, and according to the researchers the survival rate falls within the normal range for typical litters.

The mice’s mission was originally intended to last only five to seven days, during the overlap between the two space crews. Because of the delay, the mice ran short of food, and the astronauts had to share their own rations, after ground teams conducted experiments on Earth to determine which components of astronauts’ meals would also be suitable for rodents.

Researchers at the Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) reported that the surviving pups are nursing and developing normally, and are active and healthy. “This mission showed that short-term space travel did not impair the reproductive capability of the mouse,” said CAS institute researcher Wang Hongmei. “It also provides invaluable samples for the investigation of how the space environment influences early developmental stages in mammals.

The researchers plan to continue monitoring the newborn mice to ensure they can also produce healthy offspring. In this experiment, the female conceived shortly after returning from space. Future studies aim to extend the duration and scope of activity in space, ultimately enabling mice to complete an entire reproductive cycle—from conception through birth and nursing to maturity and the production of a new generation. The goal is to study mammalian development in order to better understand whether long-duration space missions could affect human fertility and whether humans might one day be able to have children on the Moon, Mars, or even farther afield. “The findings will be critical to assessing the feasibility of long-term human survival and reproduction in space — and may also deliver insights beneficial to human health on Earth,” said Huang Kun of the Technology and Engineering Center for Space Utilization at the Chinese Academy of Sciences

A stay of several weeks in space did not affect fertility. Two of the mice in the experiment at the Chinese space station | Photo: CAS, Xinhua

Public Servers

The European Space Agency (ESA) has confirmed reports that hackers breached its computer servers and stole data. A hacker using the alias “888” offered for sale 200 gigabytes of data allegedly stolen from ESA’s servers, including confidential documents, software source code, employee access passwords, configuration files, and more. The agency confirmed in a Tweet on X that the breach involved servers outside its corporate network. “Our analysis so far indicates that only a very small number of external servers may have been impacted. These servers support unclassified collaborative engineering activities within the scientific community. All relevant stakeholders have been informed,” the agency wrote. It added, “We have initiated a forensic security analysis—currently in progress—and implemented measures to secure any potentially affected devices.”

ESA servers have been breached previously, with data theft incidents occurring in 2011 and 2015. In the holiday season of 2024, hackers took a different approach, breaking into the agency’s online gift shop and stealing customers’ personal information.

A fourth data breach (at least) in the past 15 years. The European Space Agency office in Paris | Photo: ESA

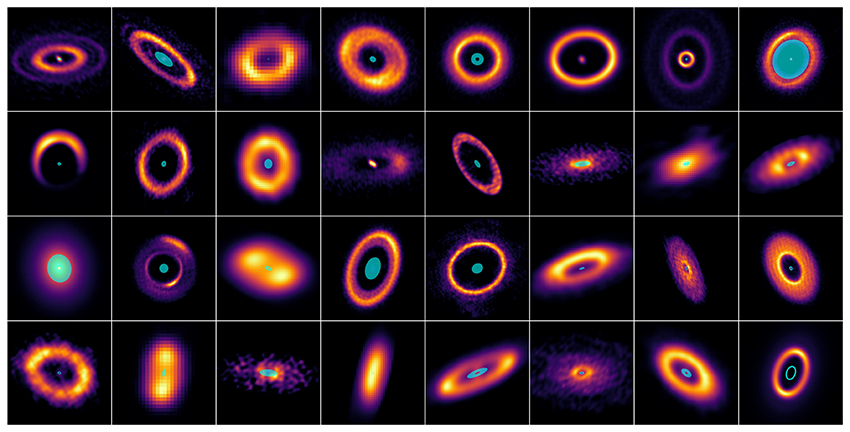

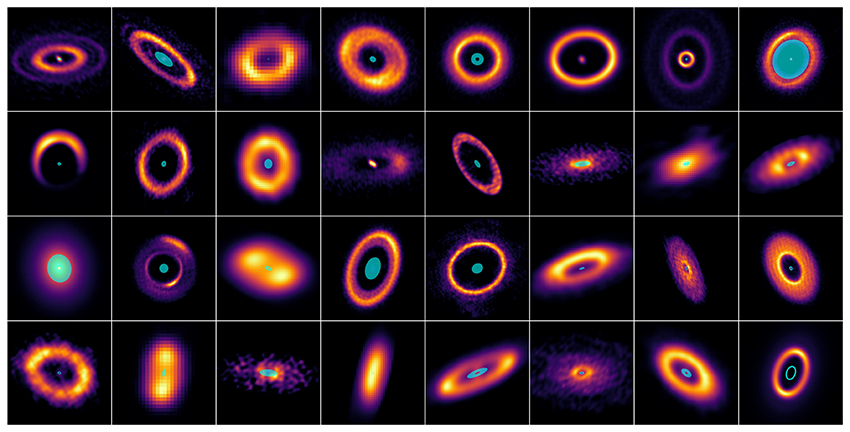

Stars Being Born

Over the past decades, astronomers have discovered about 6,000 planets in other solar systems. Now, for the first time, researchers have succeeded in identifying planet formation around young suns at the earliest stages of their development. Stars—suns—form from a rapidly rotating disk of gas and dust. As material collapses into a hot sphere, rising temperature and pressure cause it to begin emitting light and heat. Leftover material in the disk that is not accreted by the star can clump together into planets—bodies that never reach the mass needed to sustain nuclear processes in their cores. Earth and the other planets in our solar system formed this way about 4.5 billion years ago, shortly after the Sun itself formed.

When searching for planets around other stars, direct imaging is usually extremely difficult: planets are tiny compared with their host star, and the star’s glare overwhelms them. Astronomers therefore rely on indirect methods to detect planets, but these require highly precise measurements of the star itself—measurements that are difficult to apply to stars still forming, as they are often very unstable and prone to variability.

Researchers using the European Gaia space telescope have achieved what once seemed impossible, thanks to its highly precise measurements. Led by Miguel Vioque from the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the team observed very young stars in the early stages of their formation. They leveraged Gaia’s exceptional accuracy to detect subtle wobbles in the stars’ rotation, which could suggest the presence of an orbiting planet. The gravitational pull of such a planet could slightly deflect the star itself. Out of 98 young stars studied, they found potential evidence of orbiting objects around 31 of them. According to their calculations, seven of these objects are likely young planets, while eight others are probably brown dwarfs—larger-than-planet objects that didn’t accumulate enough mass to become stars. In the remaining 16 systems, the orbiting object is likely another star. The illustration below shows images of the 31 young stars and their accretion disks, captured by the ALMA telescope in Chile. The lower-right panel features a simulation of our own solar system, showing what it would have looked like at just one million years old.

The findings will be published in a paper recently accepted for publication by the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. The Gaia space telescope ended operations in April 2025 after about 12 years in space, but the vast amount of data it collected is expected to occupy researchers for years. The mission’s fourth major data release is expected in about a year, with new information on millions of stars—and likely many more planets.

Thirty-one young solar systems where gravitational effects were detected, potentially indicating the birth of planets. Bottom right: a simulation of our solar system as it would have appeared in such an image when it was just one million years old | Source: ESO, ESA/Gaia/DPAC, M. Vioque et al.