Can Neuroblastoma Be Beaten for Good? One Case Says Yes

Most patients with the rare cancer neuroblastoma die within about five years - but one girl who received an experimental CAR-T treatment remains healthy 19 years later.

In 2007, a four-year-old girl arrived at a children’s hospital in Houston, Texas, with neuroblastoma. In this cancer, malignant cells arise from neuroblasts—embryonic nerve cells—and tumors can develop along the spine or in the abdomen, chest, neck, pelvis, or adrenal gland. Five years after diagnosis, the survival rate for children with neuroblastoma is about 60%. At the time, standard treatments failed to halt the disease, which had spread to her bones. She then received an experimental CAR-T therapy as part of a clinical trial: her T cells were collected, genetically engineered to recognize a specific protein on her cancer cells, and then infused back into her body to attack the tumor while sparing other cells. Nature Medicine reported that 19 years later she remains healthy and a mother of two. To date, this is the longest cancer remission reported following CAR-T therapy.

The clinical study ran between 2004 and 2009 and included 19 participants aged three to 20. All had been diagnosed with neuroblastoma and were at different stages of disease or recovery. Eight had no active disease when they received CAR-T but were treated because of their history of cancer. The remaining 11 had active disease at the time of treatment, and some had bone metastases.

Of the eight children who were cancer-free when they received CAR-T, five remained cancer-free 10 and 15 years later. However, because they had no active disease at the time of infusion, it is unclear whether their outcomes reflect the effect of earlier therapies or of CAR-T itself. By contrast, among the 11 children treated with active cancer, three achieved complete remission and one had a partial response. Years later, one of the complete responders relapsed with widespread disease, while the other two remained healthy. One stayed healthy for more than eight years but was lost to follow-up, so their current status is unknown; the girl who was treated at age four has remained healthy to this day (2026), 19 years after treatment. She has not needed further anti-cancer treatment since, and she may be the longest-surviving cancer patient reported after CAR-T therapy.

Twelve of the 19 participants died between two months and seven years after treatment due to recurrent, spreading cancer. The other seven were still alive at their most recent follow-up, eight to 18 years after receiving the therapy.

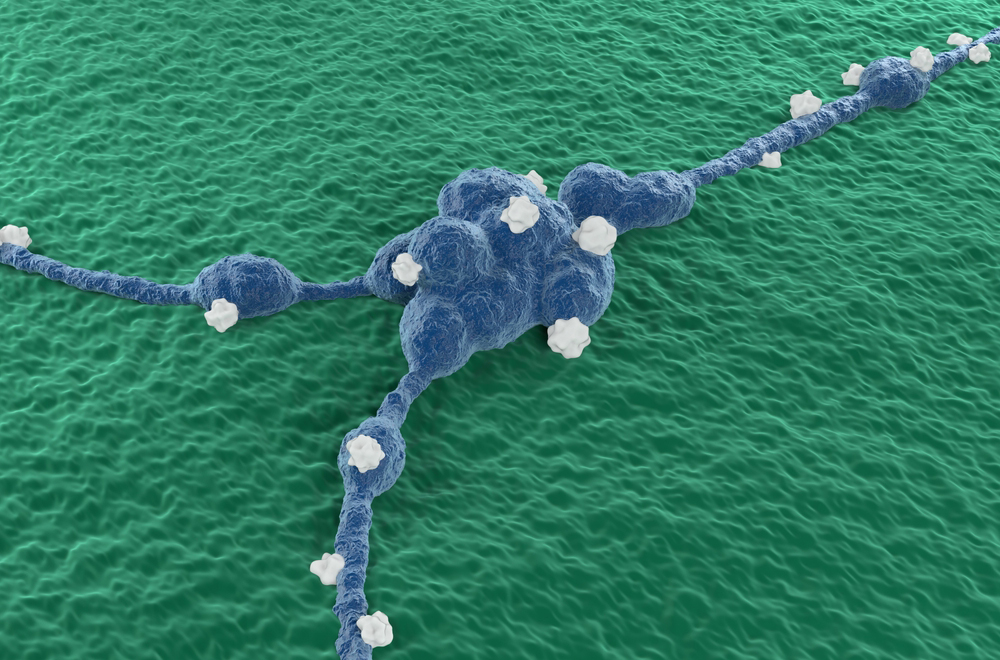

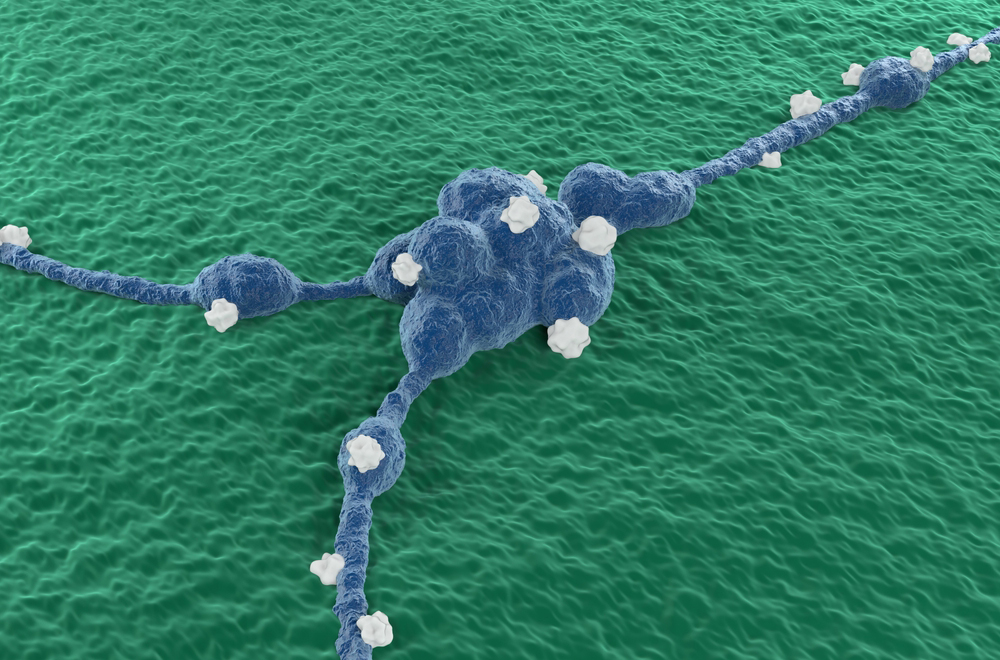

In 2007, a four-year-old girl arrived at a children’s hospital in Houston, Texas, with neuroblastoma. Nineteen years after a treatment that led to complete remission, she remains healthy. Illustration of neuroblastoma cells | Nemes Laszlo / Science Photo Library

The Body Remembers the Therapy

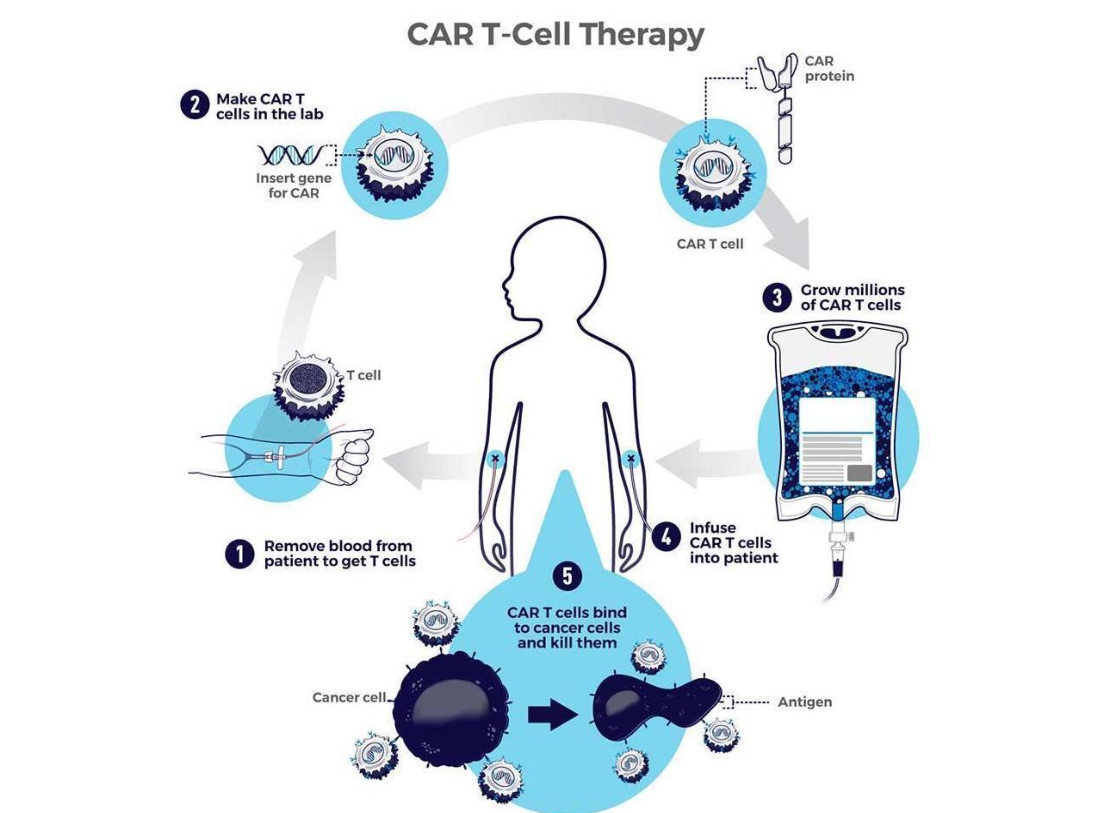

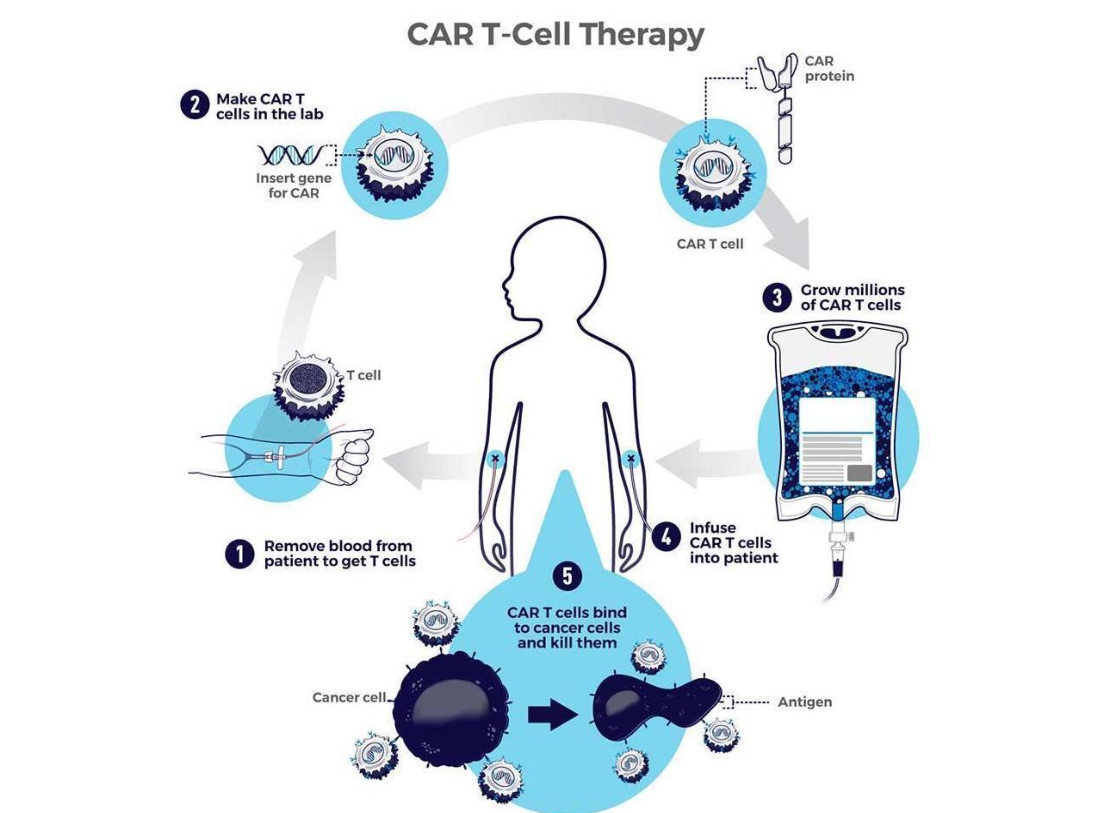

CAR-T therapy uses a patient’s own T cells, which are collected and genetically modified. The cells are engineered to carry a receptor that recognizes proteins on the cancer cells—hence the name: a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) on T cells. The engineered cells are then infused back into the body, where they can seek out and destroy the cancer cells. Because the cells originate from the patient’s own body, the immune system typically does not recognize them as foreign or reject them.

In this study, the reinfused cells contained a DNA sequence that acted like a barcode. A simple blood test can detect this sequence, allowing researchers to identify the engineered cells in the bloodstream. This made it possible to check, years after treatment, whether the cells are still present in the recipient’s body.

One year after treatment, engineered cells were still detectable in the blood of eight of the 19 patients, and in five of them the cells were still present after five years. Twelve years after treatment, researchers collected blood from three patients, grew the cells in the lab, and found that the engineered cells were still active and capable of dividing. In one patient, engineered cells were detected 13 years after treatment, but no further blood samples were taken, so it is unknown how long the cells persist in those who were treated and are still alive.

CAR-T therapy involves collecting T cells from a patient and genetically modifying them. Illustration of the treatment | NIH, National Cancer Institute

Hope Alongside the Obstacles

Most of the children who took part in the clinical trial did not survive, but in 2007 engineered T-cell therapy was still in its infancy. Today, seven CAR-T–based treatments are approved for blood cancers such as lymphoma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma – but none are approved for solid tumors like the neuroblastoma examined in this study.

Clinical trials of CAR-T cells in solid tumors have shown progress in recent years, but results still lag behind those seen in blood cancers. One reason is toxicity: the proteins CAR-T cells are designed to recognize can be present not only on cancer cells but also on healthy tissues, leading the engineered cells to attack both. This problem is generally less pronounced in blood cancers, where malignant cells circulate in the bloodstream rather than forming a mass embedded among healthy tissues. Other reasons include the difficulty CAR-T cells have in infiltrating solid tumors and the suppressive mechanisms tumors use to blunt immune-cell killing within the tumor microenvironment—challenges that are less relevant when targeting cancer cells circulating in blood.

Against that backdrop, the neuroblastoma patient treated with CAR-T who remains healthy 19 years later underscores both the importance of the trial and the technology’s potential. CAR-T has advanced considerably since then, but key questions remain. Understanding what enabled the engineered cells to eliminate solid tumors in the patients who responded—and why the treatment failed in others—could help refine CAR-T so it becomes effective for solid tumors as well.