Head of the ISA Steps Down: This Week in Space

The director of the Israel Space Agency concludes his tenure, a Chinese experiment successfully simulates a lunar landing, the upgraded configuration of the Vulcan rocket lifts off for the first time, and a promising exoplanet is revealed to be a cosmic disappointment.

29 September 2025

|

6 minutes

|

Oron. The End

The Director of the Israel Space Agency, Uri Oron, will step down in about two months. Oron, 58, a retired brigadier general in the Israeli Air Force, was appointed to a four-year term in 2021. Sources in the Ministry of Science said he recently decided not to request an extension of his tenure.

The Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology told the Davidson Institute website that immediately after receiving his resignation notice, it contacted the Civil Service Commission to begin the process of forming a search committee for the position. Once the necessary approvals are granted, the ministry will publish a tender for the position. A search committee, chaired by Director-General Omer Shechter, will then be tasked with reviewing candidates for the senior role.

Chose not to seek an extension of his tenure. The Director of the Israel Space Agency, Uri Oron (left), signs an agreement with his Italian counterpart, Teodoro Valente, at the Space Conference in Tel Aviv, January 2025 | Photo: Ettay Nevo

On the Way to the Moon

China has recently completed a successful test of the lander it intends to use for sending astronauts to the Moon within the next few years. The spacecraft, named Lanyue (meaning “Embrace the Moon” in Mandarin), resembles the Apollo lunar module in size and general appearance. In the trial, the craft was suspended from a massive structure simulating lunar gravity, which is about one-sixth that of Earth’s. The large test facility, in Hebei Province in northeastern China, was also adapted for the experiment: its floor was coated with material mimicking lunar dust in reflectivity, and rocks and craters were added to simulate a Moon-like terrain.

The test assessed the lander’s descent and ascent systems, guidance and control mechanisms, and its resilience to withstand mechanical stress and loads. “The test involved multiple operational conditions, a lengthy testing period, and high technical complexity, making it a critical milestone in the development of China’s manned lunar exploration program,” announced China Manned Space Agency (CMS) in a statement.

China has released only limited details about its goal of landing humans on the Moon by 2030, but several major differences from the Apollo program are already clear. Unlike the American lander—whose upper stage lifted off while its base remained behind as a launch platform—the Chinese craft is designed to descend and return to orbit as a single unit. It also features four engines, compared with Apollo’s single descent engine. Another key distinction lies in mission architecture: whereas Apollo launched the lunar lander together with the command/service module, China plans to launch the two separately and dock them in space. This strategy makes it possible to rely on smaller rockets than the Saturn V, but at the cost of greater operational complexity.

China aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030 and establish a crewed base there by 2035, with some elements planned in cooperation with Russia and other partners. Its lunar program is progressing rapidly: just last year, China became the first nation to return soil samples from the Moon’s far side in a robotic mission.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Artemis program – aimed at returning humans to the lunar surface—is facing repeated delays, and SpaceX’s Starship, the spacecraft designated to land astronauts on the Moon in 2027, has yet to complete even a single orbital flight around Earth. Other parts of the program are under threat of cancellation amid looming budget cuts. As things stand, there is a growing possibility that the next human to set foot on the Moon will be carrying a Chinese flag to plant in its soil.

Successful simulation of lunar landings under varying conditions. The Lanyue lander at the Hebei test facility | Photo: China Central Television CCTV

Volcanic Launch

United Launch Alliance (ULA)—the American launch corporation jointly owned by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, successfully placed a military navigation satellite last week for the U.S. Space Force. The mission marked the third flight of the company’s heavy-lift rocket, Vulcan Centaur, and its first time delivering a payload directly into geostationary orbit, 36,000 kilometers above Earth. For this launch, Vulcan was equipped with four solid rocket boosters, up from the two used on its previous missions. In geostationary orbit, satellites match Earth’s rotation, appearing fixed above a single point on the surface.

The satellite is intended to test next-generation navigation technologies, building on but surpassing those of the GPS system. It incorporates advanced anti-jamming and anti-interference capabilities to ensure reliable signal performance. Its onboard computer is designed for in-orbit reprogramming, enabling mission parameters to be updated or reassigned as required.

This was only the third launch of Vulcan Centaur overall—and the first since ULA received formal authorization to carry national security payloads, as it did in this mission. The launch effectively doubled the number of U.S. companies authorized to launch defense satellites, placing ULA alongside SpaceX in this exclusive role.

Founded in 2005, ULA was created in part to allow its parent companies to combine forces in bidding for U.S. Department of Defense contracts, establish a strong presence in the launch market, and help reduce costs. In practice, however, this was only the company’s third launch of the year, compared to 98 by SpaceX in the same period—most carrying Starlink satellites, but more than 25 on behalf of other clients, including the Department of Defense.

Still far from rivaling SpaceX. The Vulcan Centaur rocket carrying a U.S. Space Force navigation satellite lifts off from Cape Canaveral Space Center | Photo: ULA

No Air to Breathe

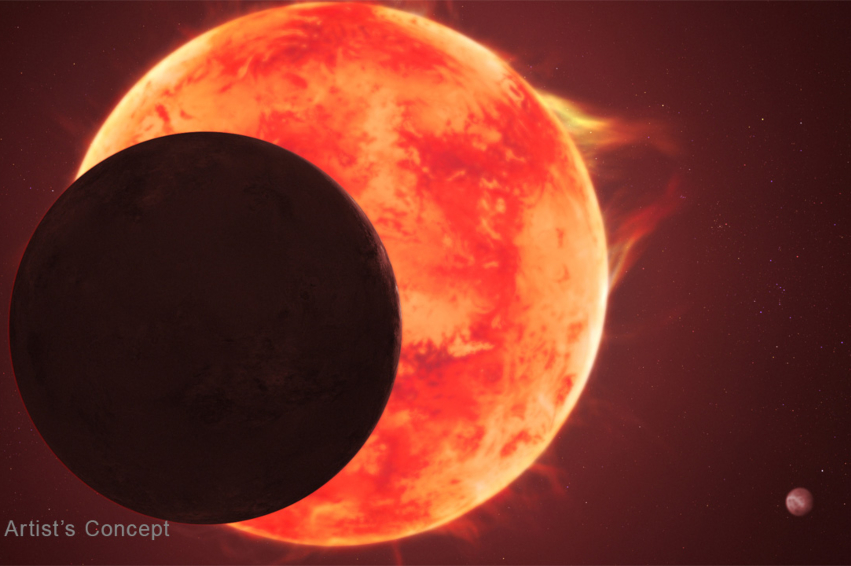

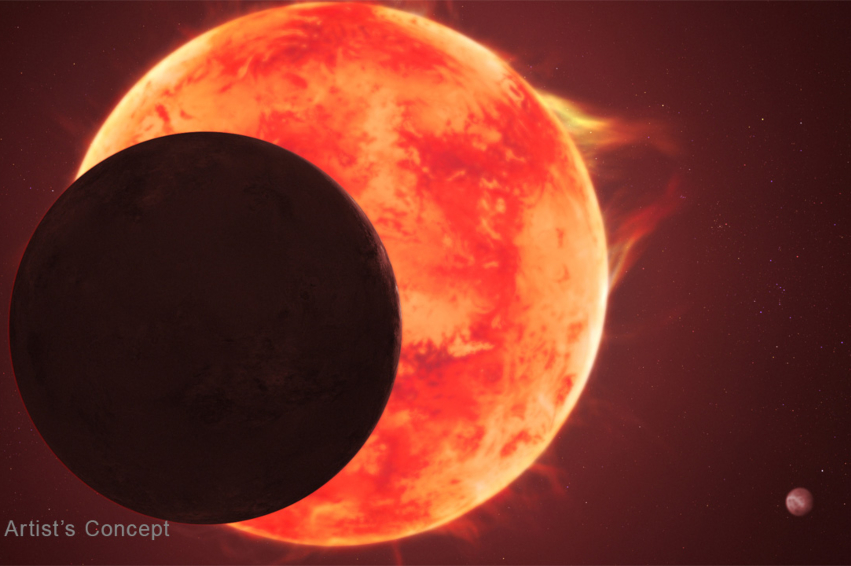

The TRAPPIST-1 system, located about 40 light-years from Earth, has captivated astronomers since its discovery in 2017. It hosts seven Earth-sized planets, several of which lie within the so-called “habitable zone”—the region around a star where temperatures might allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. But temperature alone isn’t enough to support life as we know it. A relatively thick atmosphere is also essential to retain that water and prevent it from escaping into space.

In recent years, no atmospheres have been detected around TRAPPIST-1’s two innermost planets, TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c. Now, new measurements from the James Webb Space Telescope indicate that the third planet, TRAPPIST-1d, likely lacks an atmosphere similar to Earth’s as well.

TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf star, much smaller and cooler than our Sun. TRAPPIST-1d orbits near the inner edge of the habitable zone but is still much closer to its star than Mercury is to the Sun, completing an orbit in just four Earth days. Using Webb’s infrared capabilities, an international team led by Canadian researchers conducted spectroscopic measurements of starlight passing near the planet, for atmospheric molecules such as water vapor, methane (CH₄), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and carbon monoxide (CO). Their study, published in The Astrophysical Journal, reports that no traces of these gases were detected—not even in minute amounts—greatly reducing the likelihood that TRAPPIST-1d possesses a significant, Earth-like atmosphere.

Despite the results, researchers have not ruled out the possibility that TRAPPIST-1d may still possess some form of atmosphere that escaped detection due to methodological limitations. “It could have an extremely thin atmosphere that is difficult to detect, somewhat like Mars. Alternatively, it could have very thick, high-altitude clouds that are blocking our detection of specific atmospheric signatures — something more like Venus. Or, it could be a barren rock, with no atmosphere at all,” said lead author of the study Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb of the University of Chicago and Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (IREx) at Université de Montréal.

Likely lacking an atmosphere. An artist’s impression of the exoplanet TRAPPIST-1d | Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI)