The Core Gold Rush: What Hawaiian Lava Reveals About Earth’s Deepest Secrets

Igneous rocks allow researchers to uncover the secrets of Earth’s core, and the findings are intriguing: it turns out that gold and other heavy metals can rise from deep within the planet all the way to the surface.

For many years, geologists have recognized that to study Earth’s deep interior, one must examine what happens at its surface. Just as doctors infer a patient’s internal condition through external tests to avoid invasive procedures, Earth scientists must interpret the planet’s deep internal processes using surface observations—simply because they cannot directly access Earth’s depths.

Additionally, just as doctors sometimes learn about a patient’s internal state by examining material taken from the body through a relatively minor invasive procedure, such as a blood test, geologists can learn about Earth’s internal structure by analyzing igneous rocks that reach the surface as a direct result of internal processes. Much like a patient’s blood test, volcanic rocks can reveal important information about the composition of materials and the dynamics of processes occurring deep within the Earth.

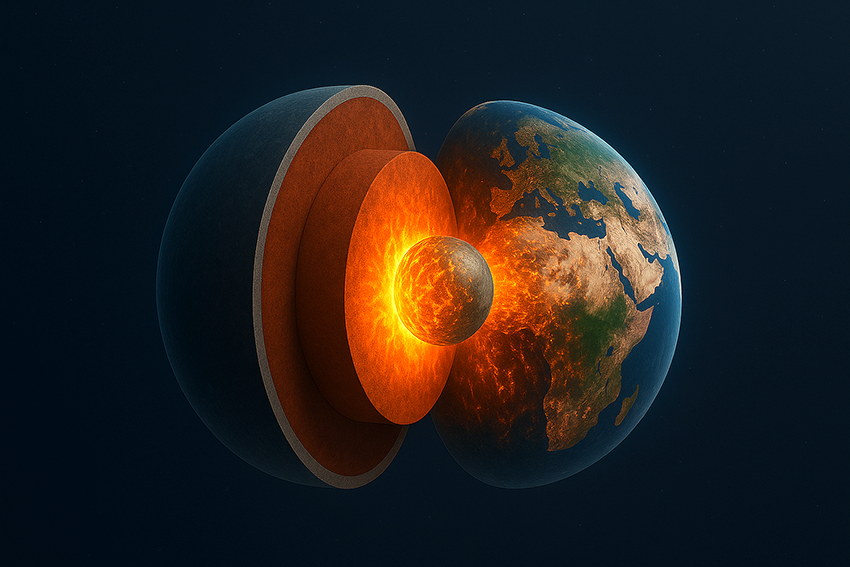

Recently, geologists conducted advanced analyses on young basalt samples erupted from volcanoes in the Hawaiian Islands. Their goal was to trace the composition of the expelled magma in hopes of identifying chemical signatures originating from great depths—perhaps even from the boundary between Earth’s core and mantle. Earth’s core consists of an inner and outer core, both enclosed by the mantle, which is itself divided into upper and lower layers. Above the mantle lies the rocky crust on which we live.

Previous studies have shown that the Hawaiian region provides a unique window into Earth’s interior because the magma erupted there is supplied by plumes rising from the lower mantle, near the boundary with the outer core, roughly three thousand kilometers below the surface. These plumes transport deep material that has remained largely unmixed with substances from the crust or surface.

Earth’s core includes an inner and outer core, both surrounded by the mantle, which is divided into upper and lower layers. Above the mantle lies the rocky crust on which we live.. Illustration of Earth’s structure | University of Göttingen, OpenAI

The Heavier, the Better

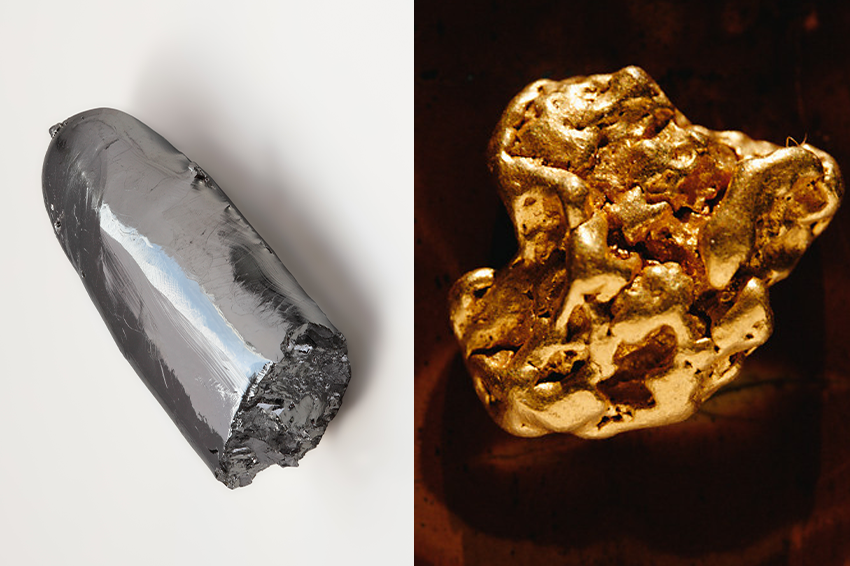

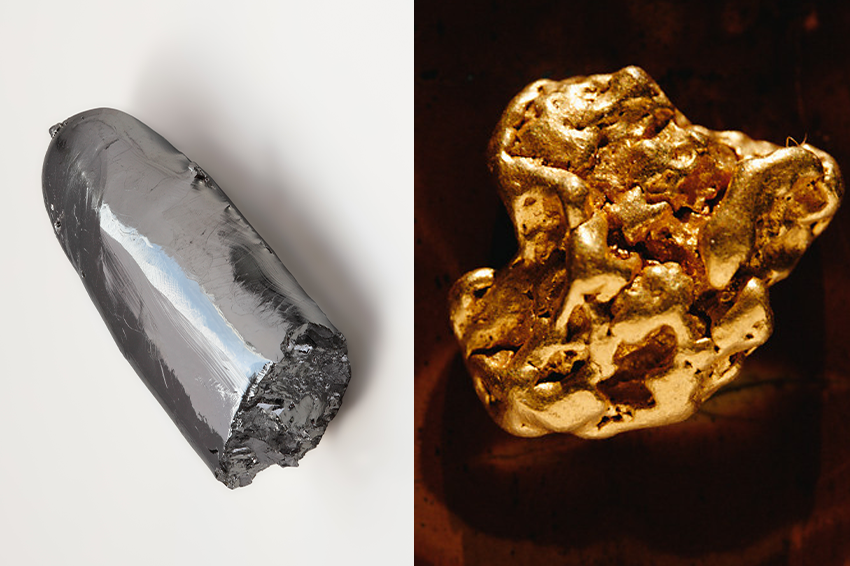

What materials were the researchers looking for? First, heavy elements such as gold, platinum, and ruthenium—whose presence could indicate that the magma truly originates from great depth. Gold and platinum are known as noble, precious metals, while ruthenium, a transition metal, is widely used in industrial applications such as electronics. These elements have relatively “heavy” atoms, meaning their nuclei contain a large number of protons. They are far more abundant in Earth’s core because during the planet’s formation, about 4.5 billion years ago, most heavy and precious metals sank toward the center and accumulated in the core, leaving only tiny amounts outside it, in the crust and mantle. For example, an estimated 99.9 percent of all the gold on Earth is concentrated in the core.

Beyond identifying which elements were present, the researchers also examined their isotopic composition. Chemical elements can have different isotopes—versions of the same element with the same number of protons and electrons (and therefore similar chemical properties) but with different masses. These mass differences arise from varying numbers of neutrons in the nucleus and can affect the physical stability of the element. For some heavy isotopes, the additional neutrons can make them radioactive, while others remain stable. While light isotopes are more common at the surface or in the shallow subsurface, heavy isotopes tend to concentrate in Earth’s core.

The isotopic ratios in the basalt samples were measured using a mass spectrometer—essentially an “atomic scale.” This instrument separates different isotopes of the same element based on their mass and allows for highly precise measurements of their relative abundances. Using this method, the researchers were able to determine the isotopic composition of the heavy elements. To their surprise, they found in the volcanic rocks an unusually high concentration of a relatively rare and heavy isotope of ruthenium, Ru-100. This isotope is found in high concentrations in the core and in lower concentrations in the mantle. In addition to Ru-100, the researchers detected traces of other precious metals, including gold and platinum, which are also considered abundant in Earth’s core but not in the mantle.

Heavy elements such as gold, platinum, and ruthenium may indicate that the magma originates from great depth. Gold (right) and ruthenium | Wikimedia, Alchemist-hp; Dirk Wiersma / Science Photo Library

“We Had Literally Struck Gold”

The researchers conclude that the high concentrations of the ruthenium isotope, together with the presence of heavy metals, indicate a process in which material originating from the boundary between the core and the mantle rose upward and eventually reached the surface through volcanic activity. Since such metals are expected to remain concentrated in the core, their elevated levels in mantle-derived rocks support the conclusion that this material leaked from a deep source at the core–mantle boundary.

“When the first results came in, we realized that we had literally struck gold,” said Nils Messling, a geochemist at the University of Göttingen, in an interview with Popular Science. “Our data confirmed that material from the core, including gold and other precious metals, is leaking into Earth’s mantle above.”

These findings are scientifically significant because they show that material from the core—long considered isolated and inaccessible—can ascend and reach the surface, carried upward by rising magma plumes. This represents a major shift in our understanding of Earth’s internal dynamics. Moreover, the sensitivity of the measurement methods demonstrates how surface rock samples can reveal processes occurring deep within the planet, even enabling identification of the chemical signatures, elements, and isotopes of materials in regions previously considered beyond the reach of direct investigation.