A Comet from Another Solar System and Two Rescue Missions: This Week in Space

NASA releases new images of a comet from beyond the solar system, new research questions the New Space revolution, and rescue missions target Chinese astronauts and an American space telescope. This Week in Space.

21 November 2025

|

14 minutes

|

“It Looks Like a Comet – Not Like a Spacecraft”

NASA released new images this week of the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS, first identified in early July. This is the third documented object known to have arrived from another solar system. The images were captured by a wide array of space missions that were briefly redirected to observe it, including space telescopes, solar-monitoring spacecraft, satellites orbiting Mars, and even the Perseverance rover on the Martian surface, which photographed it from tens of millions of kilometers away. Despite the range of cameras and instruments, most of the images are extremely blurry, taken from great distances with equipment not designed for this purpose.

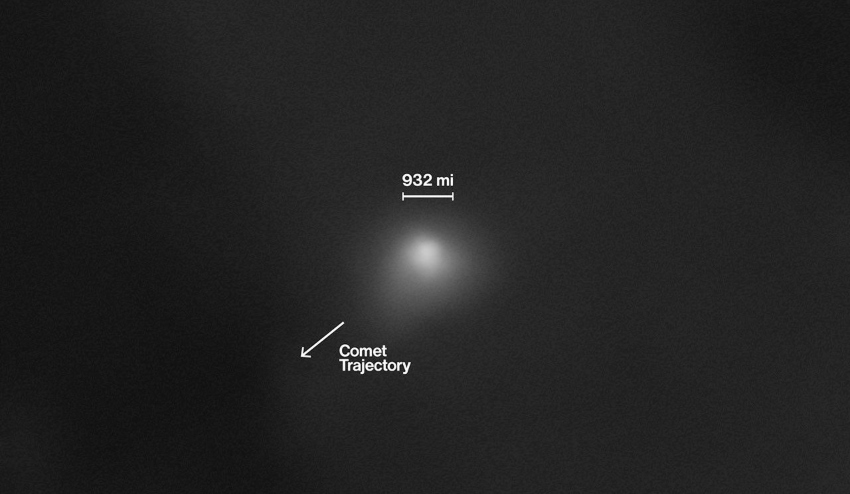

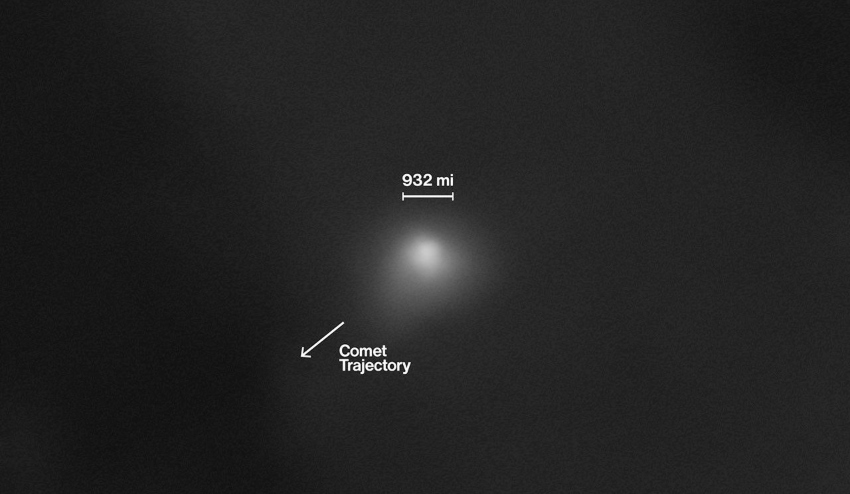

Nevertheless, most researchers are confident the object is a comet, not an artificial structure. In an image taken by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) from about 30 million kilometers away, the comet’s gas halo is clearly visible, appearing as a roughly spherical envelope about 1,500 kilometers across. “The image is blurry because the orbiter’s camera is calibrated for photographing Mars with exposures of one hundredth of a second, not for a three-second exposure,” explained the mission’s principal investigator, Alfred McEwen of the University of Arizona, in an interview with The New York Times. “It definitely looks like a comet,” McEwen emphasized. “Yes, it’s blurry. It has a halo. It doesn’t look like a spacecraft.”

NASA spokespersons at the NASA press conference also stressed that there is no evidence suggesting the object might be artificial. “It looks and behaves like a comet, and all evidence points to it being a comet,” said NASA deputy administrator Amit Kshatriya. “You kind of know the signatures that you’re looking for; we were quick to be able to say, ‘Yep, it definitely behaves like a comet’” added Nicola Fox, the associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “We certainly haven’t seen any technosignatures or anything from it that would lead us to believe it was anything other than a comet.”

Not everyone is convinced. Astrophysicist Avi Loeb of Harvard University argues that NASA is not fully considering the possibility that the object could be extraterrestrial technology rather than a natural comet. “When monitoring an interstellar visitor, we should not fall prey to traditional thinking but scrutinize new interpretations,” Loeb wrote.

Even if 3I/ATLAS is a comet, as most of the scientific community believes, we still lack a great deal of information about it. For now, researchers are concentrating on calculating its trajectory, and its exact size remains uncertain because the surrounding gas halo obscures the nucleus. Current estimates range from a few hundred meters to about three kilometers in diameter. Scientists hope that analysis of the images and measurements collected in recent weeks—released only now due to the prolonged U.S. government shutdown—will eventually yield new insights into the interstellar comet. According to some hypotheses, it may have formed even before our solar system, and researchers hope that a precise reconstruction of its path will allow them to trace it backward and determine where—and when—this intriguing visitor originated.

A view from about 30 million kilometers away, taken by a camera not designed for this purpose. The comet 3I/ATLAS as documented by the MRO Mars orbiter; the gas halo is about 1,500 kilometers across | Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

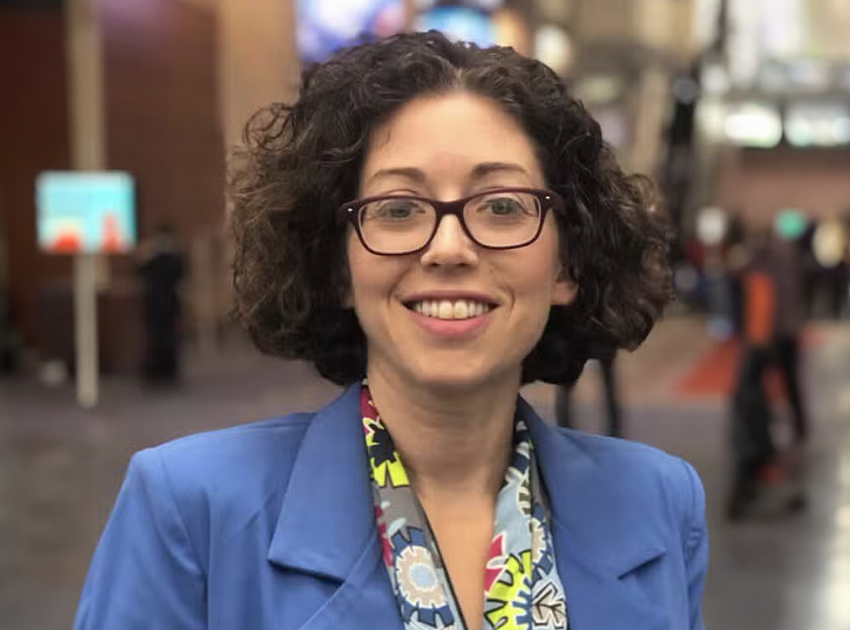

“This Is Not a Revolution – It’s Policy”

In 2024, the United States set an all-time record with 156 launches to Earth orbit in a single year. Of these, 134 were carried out by one private company—Elon Musk’s SpaceX. Both records were surpassed again this year, and the trend of private-sector dominance continues. How did the United States move from near-total government control of space activity in the early decades of the space age to a landscape in which private entrepreneurs are the dominant force, while the government primarily serves as regulator and strategic leader and coordinator? “Contrary to common perception, this is not a revolution but a gradual development that stems largely from shifts in government policy,” explained Dr. Dganit Peikowsky of the Department of International Relations at the Hebrew University, an expert in techno-strategy whose recent study on the topic was recently published in the journal Space Policy. “Our conclusions challenge the view that this is an outside revolution driven by technological or budgetary changes, and instead show it to be a gradual, cumulative process—three waves that build on one another in how space power is understood and how it is implemented organizationally and practically,” Peikowsky told the Davidson Institute website.

Peikowsky refers to the first wave, which began with U.S. space activities in the mid-20th century, as “exploration.” “At this stage, the main purpose of space missions was to demonstrate capability and project power, with no direct benefit to citizens or taxpayers. During the Apollo era, 75 percent of NASA’s budget went toward landing humans on the Moon, and only 25 percent to everything else. True to the Western model, industries built spacecraft and rockets as government contractors, with no independent goals of their own and without the development of a real commercial market—aside from satellite communications, which grew only partially at the time.”

A shift began in the late 1970s, when a new perception took shape: space power focused on “exploitation” of space technologies. “This period is marked by a change in priorities: in the 1980s, 75 percent of the U.S. space budget went to national security and only 25 percent to NASA. Key developments included space systems for broad defense activity, advanced imaging satellites, navigation systems like GPS, and proof that these technologies could serve as force multipliers on the battlefield—as demonstrated in the First Gulf War in 1991. During this process, a commercial market for space technologies began to emerge, and the U.S. government launched privatization efforts,” Peikowsky said. “After the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the U.S. recognized the strategic importance of space technologies, but government budgets were limited. The state’s deeper integration with the private sector and its expansion, since private industry could develop and manufacture systems more cheaply. This laid the groundwork for public-private joint ventures.”

These developments laid the foundation for what is often called the “New Space revolution.” Peikowsky sees this as the main component of the second wave, which led into a third wave in which space power is also viewed as “expansion.” The turning point, she says, came around 2010, when the government gradually shifted to a management model in which it no longer directly oversees or runs space activities, but instead coordinates an ecosystem of companies. “Against the backdrop of the processes I described, private entrepreneurs realized there was now a viable market for them to enter. Without the policy shifts, we would not have reached this point. It’s not that someone in government crafted a master plan; rather, this is the result of many small steps,” Peikowsky explained. “Because the government is such a central player in space, private entrepreneurs won’t move forward unless they see governmental commitment. Thus, the government shifted from being the body that directs the industry to what is called an ‘anchor customer’ – ordering services but not engaged in detailed management of how they are executed.”

The study focuses on the United States because it is the global leader in space activity, invests more in the field than all other countries combined, and is a transparent democracy whose policies are publicly documented. Peikowsky and her colleagues are now expanding their research to examine these processes on a global scale. One interesting case is China, which sees itself as a competitor to the U.S. “China also understands that a decentralized ecosystem is the right model, but in recent years it has somewhat stepped back from opening its space and technology markets,” Peikowsky noted. “The U.S. strategy for responding to China is not to pour more money into its space industry, but to build broader international partnerships—which is a challenge in itself.”

Seeking to challenge the perception that this is an external revolution and to show that it is a gradual, cumulative process. Dganit Peikowsky | Photo: Benny Sharoni

A Private Mission to Save a Public Telescope

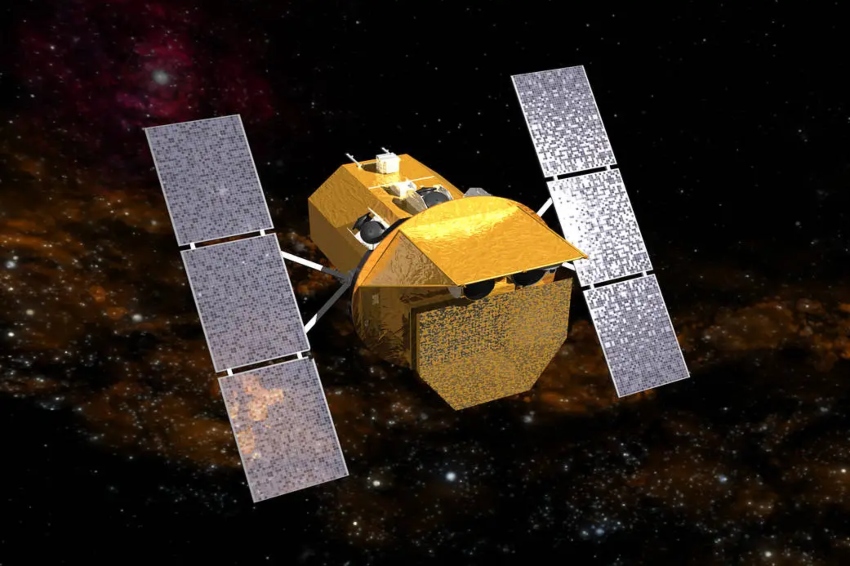

A concrete example of how the government assigns missions to private companies but does not direct their operational execution came just this week, when the American company Katalyst announced that it would carry out a rescue mission for NASA’s Swift space telescope using a rocket launched from an aircraft.

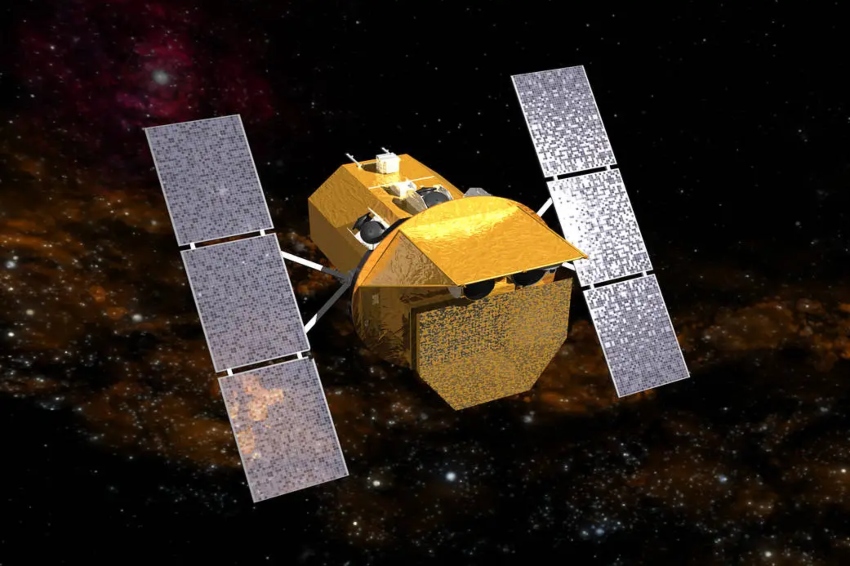

The telescope was launched in 2004 to study gamma-ray bursts—cataclysmic cosmic events that release immense amounts of high-energy radiation in extremely short timescales. Swift has produced many scientific discoveries, but over the years it has been steadily losing altitude. From its original orbit of about 600 kilometers, it has dropped to roughly 400 kilometers today. Although the atmosphere at these altitudes is extremely thin, it is still dense enough to produce aerodynamic drag, which gradually slows spacecraft and causes their orbits to decay. Swift has no propulsion system to maintain or adjust its orbit, and its rate of descent accelerates as it sinks into denser layers of the upper atmosphere. If nothing is done, NASA estimates that the telescope will reenter and burn up in the atmosphere in about a year, around the end of 2026—leaving the agency without an active space telescope operating in these energy ranges.

The solution is to launch a rescue mission: a spacecraft that will dock with the telescope and use its own engines to raise it into a new orbit. In September, NASA selected the Arizona-based company Katalyst to carry out the mission at a cost of about 30 million dollars, including the launch. This week, the company announced that it plans to launch the spacecraft aboard Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus rocket. Pegasus is released from an aircraft at an altitude of about 12 kilometers, after which it ignites its engines. The rocket can deliver a payload of roughly 500 kilograms to low Earth orbit. It entered service in 1990, and since then several versions have flown 45 space missions, 40 of them successful. The choice of Northrop Grumman is expected to streamline development of the rescue mission, since in 2018 the company acquired the final iteration of Orbital—the firm that originally built the Swift telescope. “We have to do some final integration and test, and we have to develop the trajectory and the guidance for the RAAN [right ascension of the ascending node] steering and software, but that’s really it,” said Northrop Grumman’s director of space launch for Katalyst, Kurt Eberly.

Katalyst aims to launch the rescue spacecraft in June 2026. The vehicle, with a mass of about 350 kilograms, is expected to enter Swift’s orbit, inspect the telescope up close for two to three weeks, then attach itself using three robotic arms and carry it to a higher orbit. The mission poses significant challenges: Swift was not designed for docking, so engineers will need to improvise attachment points. Operators must also ensure that during orbit raising, the telescope’s sensitive optical instruments never point toward the Sun—or even toward Earth or the Moon—since reflected light could damage them. Despite these hurdles, the company remains optimistic that it will meet the schedule and save the telescope.

A tight schedule to save a telescope that is rapidly losing altitude. Illustration of the Swift space telescope in orbit | Illustration: NASA

A Chinese Rescue Mission

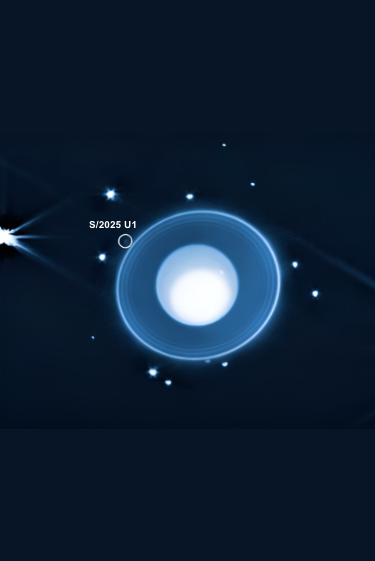

China is expected to launch an uncrewed spacecraft to its Tiangong space station as early as next week, providing a crucial safety backup for the crew currently aboard, who have no means of evacuation in an emergency. The three astronauts of the Shenzhou-21 mission arrived at the station about three weeks ago. The crew they relieved, Shenzhou-20, was supposed to return to Earth after several days of handover, but the China National Space Administration delayed their departure after a crack was discovered in the window of their docked spacecraft. The crack may have been caused by space debris or a tiny meteoroid. Ultimately, the astronauts returned to Earth in the spacecraft that had delivered the Shenzhou-21 crew, landing safely last Friday. Their departure, however, left the station crew without a functional escape vehicle in the event of an air leak, fire, debris strike, or another emergency or malfunction.

According to unconfirmed reports, China is preparing to launch the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft as early as next week, likely on November 25, and it will carry no crew. In addition to serving as a lifeboat, the spacecraft will deliver water, food, oxygen, and other consumables depleted during the two weeks in which the station was occupied by two crews instead of one. The launch is expected to push back the arrival of the next crew, originally planned for April or May 2026. Continuous occupation of the station is not required, however, and the current astronauts will be able to complete their mission in the spring and leave the station uncrewed until their successors arrive.

In the meantime, the Chinese space agency is expected to return the damaged spacecraft still docked to the station. It will be undocked and attempt an autonomous landing so that engineers can determine whether the damage posed a genuine risk to the crew. If the landing is successful, investigators may also identify the cause of the impact and explore ways to reduce similar hazards in the future.

Landed safely. Ground crews assist the Shenzhou-20 astronauts as they exit the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft after landing in the Inner Mongolia desert, northern China | Photo: CCTV/BACC