Close Encounters of the Third Kind

An object likely originating from another solar system was spotted on July 1st, hurtling toward the center of our own solar system. This is only the third object ever identified as very likely to have come from beyond our solar system, following ‘Oumuamua, discovered in 2017, and Comet 2I/Borisov, identified in 2019. Researchers believe this newly detected object is also a comet and have temporarily named it 3I/ATLAS—denoting the third interstellar (3I) object and the ATLAS telescope array that first spotted it.

Although still distant, 3I/ATLAS is moving at over 200,000 kilometers per hour relative to the Sun, and is expected to accelerate further as it approaches the Sun, due to the Sun’s gravity. It was first detected by a telescope in Chile, forming part of NASA’s ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) network, which scans for objects that might collide with Earth.

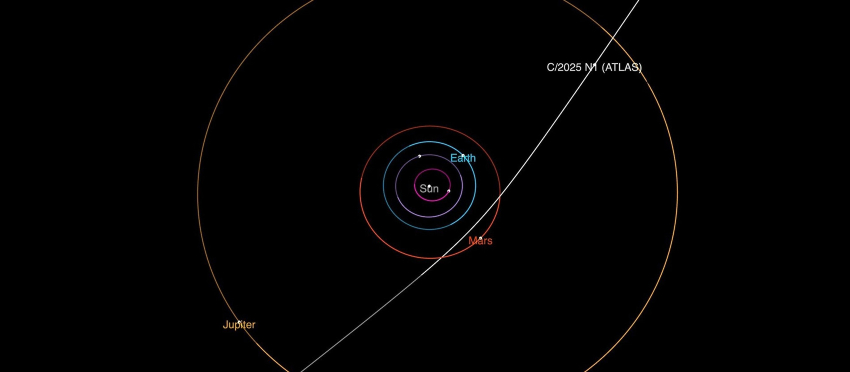

An amateur astronomer then spotted the object in earlier ATLAS photos taken in late June. The International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center has reported over 100 observations from telescopes around the world. 3I/ATLAS remains currently too bright and too distant to accurately determine its size. It’s currently located between Jupiter’s orbit and the asteroid belt and will later cross Mars’s orbit—but it is not expected to cross Earth’s orbit or collide with our planet. At its closest approach in December, it will be about 250 million kilometers away.

Not expected to collide with Earth. The orbit of 3I/ATLAS, marked as C/2025 N1 in the diagram. | Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

“With all the observations, there is no uncertainty that the comet came from interstellar space,” said Paul Chodas, director of the Center for Near Earth Object Studies at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “The speed is too fast to be something that originated within the solar system.”

Researchers estimate that it’s a comet that formed around another star and was ejected from its own solar system by a violent event, such as a collision with another planetary body—eventually passing through ours by chance.

“If you trace its orbit backward, it seems to be coming from the center of the galaxy, more or less,” Chodas told The New York Times. “It definitely came from another solar system. We don’t know which one.”

The discovery of ‘Oumuamua nearly eight years ago caused a stir in the scientific community—and fueled the imagination of UFO and alien life enthusiasts. Their excitement was also fueled by Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb, an Israeli-American professor who in recent years has focused on the search for extraterrestrial life. Loeb sparked controversy by speculating that ‘Oumuamua might be a product of an alien civilization. Earlier this month, Loeb told The New York Times about the new object: “This is the most interesting question in my mind right now: what accounts for its very significant brightness?”

If the object is indeed a comet, as scientists suspect, its brightness likely comes from sunlight reflecting off jets of gas released from its surface. This time, astronomers will have much more time to try to solve the mystery: 3I/ATLAS will remain visible through telescopes for many months and is expected to become the focus of numerous observations from both ground- and space-based telescopes, in hopes of learning more about this interstellar visitor.

Too early to determine its size, as 3I/ATLAS is still more than 650 million kilometers from the Sun. 3I/ATLAS | Photo: K Ly / Deep Random Survey / CC-BY-4.0-SA

The Environmental Satellite That Went Silent

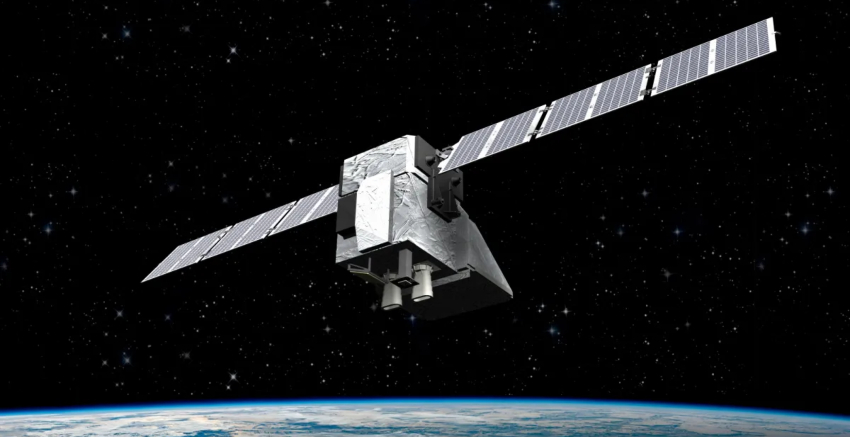

An American environmental organization announced recently that its methane-monitoring satellite has unexpectedly stopped functioning—just 15 months into what was intended to be a five-year mission. MethaneSAT was launched in March 2024 by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), a nonprofit dedicated to combating global warming and protecting the environment.

The satellite tracked atmospheric methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, whose concentration has been steadily rising in recent years, reaching record highs. Methane is released from natural sources, such as animal digestion and decomposition of organic matter in wetlands, but also from industrial leaks, particularly at oil production facilities. MethaneSAT was designed to detect such leaks so they could be repaired, helping reduce emissions.

Other satellites can detect methane, but MethaneSAT—built at a cost of $88 million with funding from Jeff Bezos’s Earth Fund—was unique in its ability to identify even small leaks and precisely pinpoint their sources. “The loss of MethaneSAT, make no mistake, represents a gap in our community’s ability to monitor and quantify methane emissions. And it’s a pretty big gap,” said Riley Duren, a remote sensing expert and CEO of Carbon Mapper, another organization working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Contact with the satellite was lost on June 20, and its operators declared the mission over after all efforts to restore it failed. According to them, the satellite’s power supply ceased for unknown reasons, and engineering teams are still trying to determine the cause of the malfunction. The organization’s chief scientist, Steven Hamburg, emphasized that there had been no prior indications of such a failure or any problems in the satellite’s power systems.

Contact with MethaneSAT was lost on June 20, and its operators declared the mission over after all attempts to restore communication failed. According to EDF, the satellite’s power supply failed for unknown reasons, and engineering teams are still trying to determine the cause of the malfunction. EDF’s chief scientist and leader of the mission, Steven Hamburg, emphasized that there were no previous indications of a problem with the satellite’s power systems.

The End of the Nuclear Spacecraft

The U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is withdrawing from the development of a nuclear propulsion system for spacecraft, a project it announced jointly with NASA about two years ago. The two agencies had selected Lockheed Martin to develop the spacecraft, known as DRACO.

Although no official cancellation has been announced, NASA’s proposed 2026 budget—significantly reduced due to administration-imposed cuts—sets funding for the project at zero, effectively signaling its termination.

DARPA Deputy Director Rob McHenry, speaking at a seminar hosted by the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, said the agency constantly evaluates its technology programs and cited two main factors in the pulling of funding for DRACO. The first is the plummeting launch costs in recent years, which undermines the economic rationale for nuclear-thermal propulsion. The second is a pivot toward nuclear-electric propulsion.

“As the launch costs came down, the efficiency gain from nuclear‑thermal propulsion relative to the massive R&D costs necessary to achieve that technology started to look like less and less of a positive ROI,” McHenry said. “So the national security operational interest in the technology was decreasing proportionally to that perception.”

The DRACO spacecraft was designed to operate with a nuclear reactor that would heat hydrogen fuel to extremely high temperatures, generating thrust through the controlled expulsion of hot gas. This approach is significantly more efficient than traditional chemical propulsion, both due to its higher energy efficiency and the fact that it doesn’t require an oxidizer, leading to a significant mass saving.

However, according to McHenry, new evaluations concluded that it would be better to pursue nuclear-electric propulsion, which uses nuclear energy to generate electricity to power an electric thruster for spacecraft propulsion. “Nuclear-electric [propulsion] is probably a more optimal long‑term solution,” he said, adding that launching a nuclear reactor into space and testing it on the ground proved more technically challenging than DARPA had initially assumed.

With its cancellation, DRACO now joins a long list of nuclear space projects, canceled over the years due to political, diplomatic, economic, military, or safety concerns. “We want to do the disruptive tech,” McHenry concluded, adding that DARPA aims to develop breakthrough technologies rather than invest heavily in upgrading existing infrastructure.

Now part of the long list of canceled nuclear space projects. Artist’s rendering of the DRACO nuclear spacecraft. | Illustration: NASA

Routine Tourism to the Edge of Space

Blue Origin successfully completed its 13th suborbital space tourism flight this week, carrying six passengers on a brief journey to the edge of space. This raises the company’s total number of space tourists to 70, out of 123 people who have flown on suborbital flights to date. The mission also marked the 750th person to cross the boundary of space.

The six tourists—five men and one woman—flew aboard the Kármán Line spacecraft, launched atop a New Shepard rocket from Blue Origin’s West Texas spaceport. The spacecraft reached an altitude of 105.2 kilometers (65.4 miles), allowing the passengers to experience several minutes of weightlessness and enjoy a unique view of Earth before safely descending and landing near the launch site approximately ten minutes after liftoff. The rocket itself completed a successful vertical landing.

As with previous flights, Blue Origin did not disclose how much the passengers paid for their tickets, though estimates suggest several hundred thousand dollars per seat.

Blue Origin celebrates 70 space tourists. The capsule descends at the end of the mission, landing near the launch pad where the New Shepard rocket also successfully touched down. | Photo: Blue Origin