The Moon Race Heats Up: This Week in Space

Elon Musk is putting the Moon at the top of SpaceX’s priorities. China successfully tested its Moon-launch rocket, a new crew arrives at the ISS, and an especially far-southern solar eclipse. This Week in Space.

17 February 2026

|

10 minutes

|

Musk Changes Course

Elon Musk’s grand plan since founding SpaceX in 2002—and the purpose behind driving Starship’s development—has been to establish a crewed colony on Mars. He has repeatedly said this goal is his top priority. As recently as about a year ago, he dismissed lunar plans as a distraction on the road to Mars, and promised he would try to launch Starship to Mars by the end of 2026. This week, however, Musk reversed course, announcing that he’s now prioritizing a self-growing city on the Moon over settling Mars – something he claims could be potentially achieved in less than a decade.

In a tweet, Musk noted that it is only possible to travel to Mars every 26 months, when Earth and Mars are relatively close, and that the journey takes about six months – whereas launches to the Moon are possible roughly every 10 days, with a transit time of about two days. “This means we can iterate much faster to complete a Moon city than a Mars city,” he wrote. Musk emphasized that “the mission of SpaceX remains the same: extend consciousness and life as we know it to the stars.”

In light of this, he clarified that “SpaceX will also strive to build a Mars city and begin doing so in about 5 to 7 years, but the overriding priority is securing the future of civilization and the Moon is faster.”

Musk has not publicly explained the reasons for the shift. Commentators have suggested one possible factor is pressure from NASA to stay on track for landing astronauts on the Moon in 2028 – or at least to do so before China, which aims to do so by 2030. SpaceX holds a roughly $3 billion contract to develop a lunar lander based on Starship. But with Starship’s development delayed and still in the early stages of testing – and amid public signals from NASA leadership that competition for developing the lander has been reopened, Musk may worry about losing the contract to Blue Origin, which has also secured a NASA lunar lander contract for future lunar missions.

Another factor could be Musk’s reported plan to take SpaceX public this year. Some economic analysts argue it may be easier to attract investors to lunar projects, where potential revenue returns could arrive sooner than with long-term, ambitious Mars plans, whose profit horizon lies much farther in the future.

SpaceX plans to resume Starship test flights next month with the first launch of the spacecraft’s third generation. Last week the company said it had completed cryogenic proof testing of the Super Heavy V3 booster slated for that launch, and that it successfully passed checks of the redesigned propellant system and overall structural strength. SpaceX will now focus on preparing the spacecraft itself for the test. So far, Starship vehicles have flown only on ballistic trajectories, without reaching Earth orbit. To meet the goal of landing humans on the Moon, SpaceX will need to demonstrate an orbital flight and on-orbit maneuvering; docking between spacecraft and in-space refueling; and, of course, a soft vertical landing on Earth before attempting the same on the Moon.

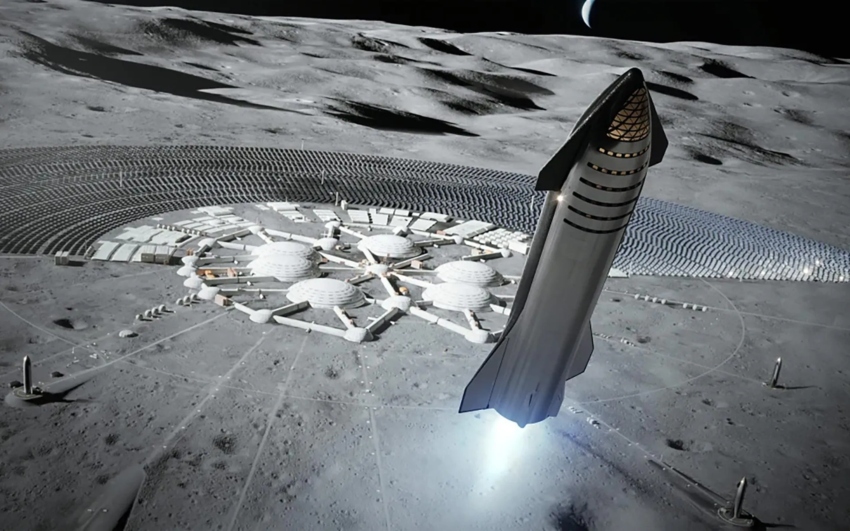

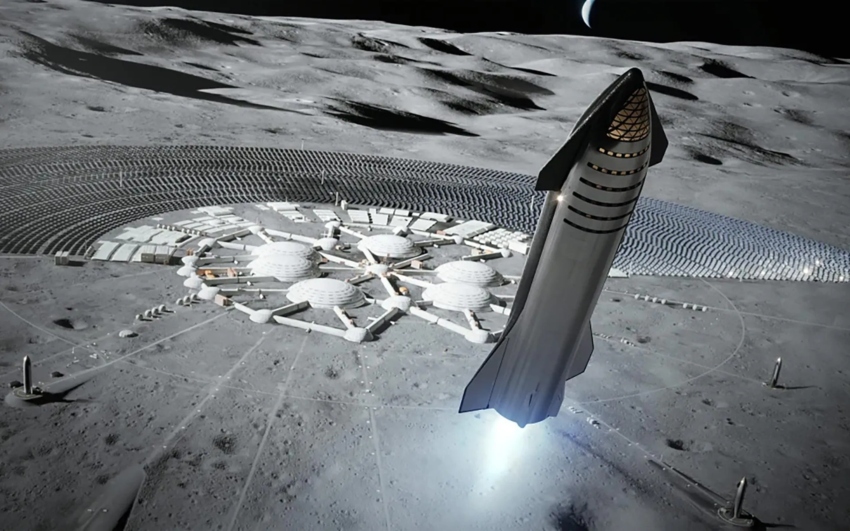

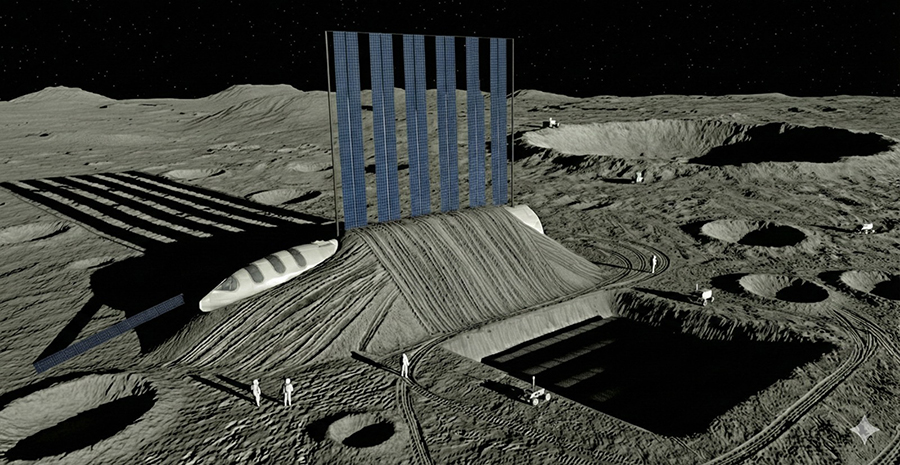

A more practical project in terms of timelines—and perhaps for attracting investors. An early rendering of SpaceX’s “Moon City” | Source: SpaceX

Elon Musk and the Israeli Lunar Program

SpaceX’s change of course has also produced a surprising boost for an initiative led by Israeli space enthusiast Dr. Shay Monat: a lunar habitat concept built around the Starship spacecraft. Monat, who recently completed a PhD in mechanical engineering, participated in the International Space University’s summer program in 2021. For his course project, he explored how SpaceX’s lunar lander could be repurposed into a living structure. Working with project partners, Monat developed a plan to lay Starship down gently on the Moon – without cranes or other heavy equipment that wouldn’t be available there—and then convert the spacecraft’s interior, including the large volume of its fuel tanks, into living and working quarters, along with a greenhouse for growing plants. “The International Space Station was constructed over years, from parts that were shipped on a large number of flights. Our solution will allow the creation, on the moon, of 2,500 cubic meters of living space – twice the size of the entire station – and on one flight,” Monat told the Davidson Institute website.

After Musk announced that SpaceX would prioritize the Moon, a space engineer resurfaced Monat’s International Space University proposal and a paper he published with colleagues. Musk himself shared the tweet, adding the comment: “This will be so awesome 🤩”

Monat now hopes to leverage the project’s newfound attention to establish a company that could turn the concept into reality—and perhaps even collaborate with Musk.

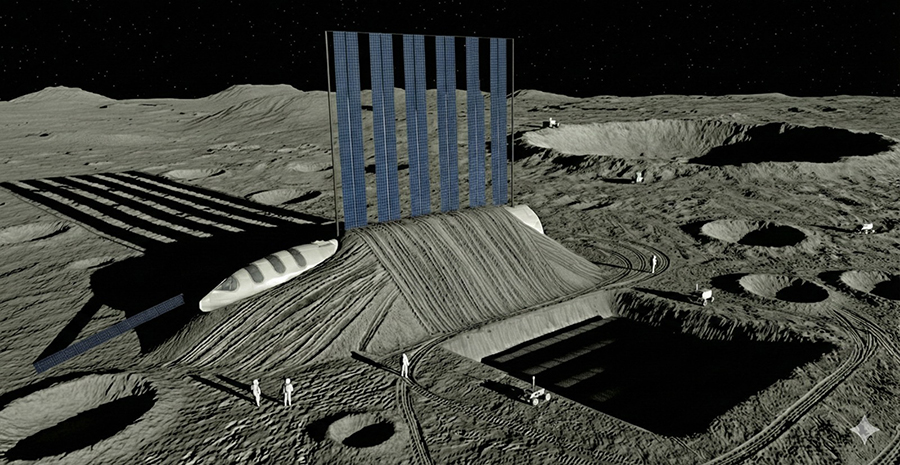

The plan is to lay Starship on its side, cover it with lunar soil for insulation and protection, and add solar arrays to generate electricity. A rendering of the habitat concept according to the plan by Monat and his colleagues. Illustration: Shay Monat, via Google Gemini.

China Takes Another Step Toward the Moon

This week China successfully carried out an important test on the path toward crewed lunar missions: a launch test of the first stage of the rocket that will carry astronauts, along with a trial of the emergency escape system designed to protect the crew in the event of a rocket malfunction.

For its lunar program, China is developing a new heavy-lift rocket called Long March 10, expected to be able to carry about 27 tons. It will be a three-stage rocket, but in last week’s test only the first stage (CZ-10) was flown, topped by the Mengzhou spacecraft, which is intended to carry humans on lunar missions. The spacecraft—whose shape is reminiscent of NASA’s Orion—was launched uncrewed for the test.

After the rocket passed the point in ascent when pressure and loads are greatest (MaxQ), the escape system was activated: a relatively small rocket mounted above the capsule, similar to the launch escape systems used on Orion and Apollo. In an emergency, it is meant to pull the spacecraft away from the rocket and allow it to descend safely by parachute. The spacecraft splashed down at sea and was recovered by a waiting ship.

The rocket’s first stage reached an altitude of about 100 kilometers, then fell freely and executed a landing maneuver over the water—apparently a step toward future recovery on a barge, in a manner similar to SpaceX boosters.

The China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) said the test successfully verified the rocket first stage’s performance during launch and landing, as well as the crewed spacecraft’s escape system performance under maximum dynamic pressure (MaxQ). CMSEO added that the test also verified the compatibility of interfaces among the relevant components and across various engineering systems, and collected flight data and engineering experience for future crewed lunar exploration missions.

Beyond testing a new rocket and spacecraft, the flight also served as a test of a new launch pad at the Wenchang Space Launch Site on Hainan Island in southern China. The statement said the launch center team “overcame various difficulties” by carrying out parallel engineering work—following a “build while using” approach—to ensure the test was conducted on schedule.

Last week’s test is another important step in China’s plan to land humans on the Moon by 2030. Under the planned mission architecture, a Long March 10 will launch Mengzhou with a three-person crew, while a separate rocket will launch the Lanyue lunar lander. The two spacecraft will rendezvous and dock in orbit, after which the lander—carrying the crew—will separate in lunar orbit for descent to the surface, similar to the approach used in the Apollo missions.

In August 2025, China conducted an initial landing test of the lunar lander in a facility simulating the Moon’s gravity. In parallel, China plans for Mengzhou to eventually replace the spacecraft it currently uses to fly astronauts to low Earth orbit, mainly to its space station. While the current Shenzhou spacecraft can carry three people to the station, the larger Mengzhou is expected to carry up to seven to low Earth orbit.

A 2:02-minute summary of the test: the launch, separation of the spacecraft from the rocket, its safe splashdown, and the booster’s landing maneuver:

A New Crew Reaches the ISS

After a brief weather delay, NASA’s Crew-12 lifted off on Friday aboard a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft atop a Falcon 9 rocket and arrived at the International Space Station the following day, restoring the outpost’s staffing after weeks with a reduced crew. The launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida, proceeded without incident, and about eight minutes later Dragon reached orbit; the crew then spent roughly 34 hours in transit before docking with the ISS. The flight was NASA’s 12th crewed mission aboard Dragon since crewed Dragon flights began. Falcon 9’s first stage also landed successfully back at Cape Canaveral, touching down on a new landing pad a few hundred meters from the launch site.

The mission briefly appeared at risk last week after SpaceX paused Falcon 9 launches following a second-stage malfunction on a Starlink mission, but the stand-down lasted only five days. SpaceX submitted an anomaly report to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) outlining corrective actions, received clearance to resume launches, and returned to flight with a Falcon 9 carrying Starlink satellites—this time with the second stage performing properly.

The four astronauts joining the space station are Jessica Meir and Jack Hathaway (United States), Sophie Adenot (France, representing the European Space Agency), and Andrey Fedyaev (Russia). They are joining the remaining station crew after Crew-11 was unexpectedly shortened last month due to a medical issue affecting one of its members.

The new arrivals restore the station to full operations after about a month with a reduced crew. Crew-12 members (from right): Sophie Adenot, Jessica Meir, Jack Hathaway, and Andrey Fedyaev | Photo: NASA/James Blair

Vulcan Rises Again

The American company ULA successfully launched two large U.S. military satellites into high orbit aboard a Vulcan Centaur rocket. It was the rocket’s fourth flight, following its entry into service two years ago.

The payload consisted of reconnaissance satellites operating in geosynchronous orbit—at an altitude of about 36,000 kilometers. At that height, a satellite’s orbital period matches Earth’s rotation, so it appears fixed over the same region on Earth at all times. Many communications, weather, and intelligence satellites operate in this orbit.

The two satellites launched on February 12 join six others in the GSSAP series—U.S. reconnaissance satellites designed to provide “space domain awareness” in that orbit, including monitoring activity there and helping prevent collisions between satellites.

The launch from Kennedy Space Center in Florida was accompanied by a malfunction in one of the strap-on solid rocket boosters attached to the core vehicle, apparently caused by damage to the exhaust nozzle through which hot gases escape to generate thrust. A similar malfunction occurred on Vulcan Centaur’s second launch. Then – and apparently this time as well – the rocket overcame the problem and delivered its payload to the intended orbit. Still, the company will almost certainly need to investigate the cause in depth to avoid endangering future payloads.

ULA is the only company besides SpaceX whose rockets have been certified to launch U.S. Space Force national security missions, and it has already received orders for more than twenty such launches.

A recurring malfunction that could endanger future launches. The Vulcan Centaur rocket lifting off from Kennedy Space Center in Florida | Photo: ULA

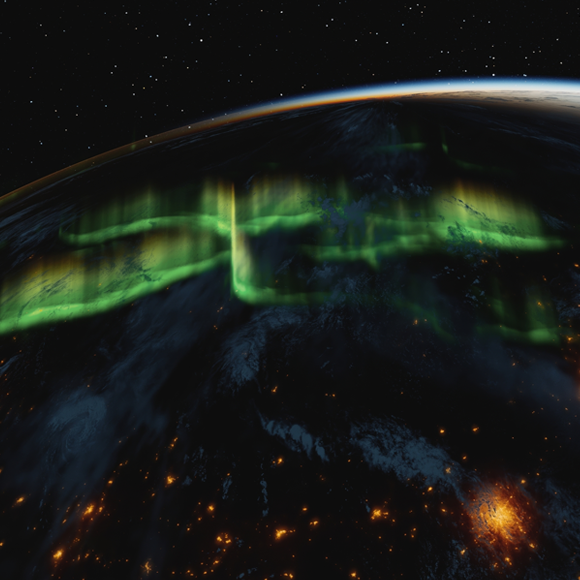

Eclipse Season in the Southern Hemisphere

On Tuesday, February 17, an annular solar eclipse will occur—but very few people will be able to see it. In an annular eclipse, the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, but because the Moon is relatively far from Earth at the time, it doesn’t cover the Sun completely, leaving a bright ring of light around the Sun’s edge.

This time, the path of annularity—the narrow track from which the “ring of fire” is visible—will pass only over Antarctica. This time, the path of annularity—the narrow track from which the “ring of fire” is visible—will pass only over Antarctica. Anyone who isn’t headed to the southern continent this week will still be able to see a partial eclipse from nearby islands, and from islands in the southern Indian Ocean such as Mauritius, Réunion, and Madagascar, as well as from South Africa. A very slight partial eclipse—covering only a few percent of the Sun’s disk—will also be visible in parts of Mozambique, Botswana, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe, and at the southern tip of Argentina.

About two weeks later, a total lunar eclipse will take place, with totality visible across much of eastern Asia and Australia, sweeping across the Pacific and into North and Central America; a partial eclipse will be visible across a broader surrounding region, including parts of central Asia and much of South America. Another solar eclipse will follow in February 2027: the annular “ring of fire” will be visible only along a track across parts of South America and West Africa, while a partial eclipse will be visible across wider areas nearby.

For the next eclipses that many people will be able to watch, look to summer. On August 28, 2026, a partial lunar eclipse will be visible across parts of the Eastern Hemisphere, with Earth’s shadow covering roughly 10–15% of the Moon at maximum. In February 2027, a penumbral lunar eclipse will be visible across wide areas—a subtle event in which Earth’s shadow doesn’t fall directly on the Moon, but slightly dims it. And on August 2, 2027, an impressive partial solar eclipse will be visible across parts of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, with the Moon covering more than 80% of the Sun in some locations.

The Moon doesn’t block the entire Sun, leaving a ring of light around it. An annular solar eclipse photographed from Tokyo in 2012 | Photo: unitaro, Shutterstock