New NASA Administrator and an Enigmatic Cosmic Blast: This Week in Space

A private astronaut has been appointed to lead the U.S. space agency, an interstellar comet is making a close pass, a Mars orbiter is in trouble, and astronomers may have spotted a new kind of cosmic event. This Week in Space

21 December 2025

|

10 minutes

|

A New NASA Administrator

The United States Senate approved—by a wide margin, 67 votes to 30—the appointment of billionaire and private astronaut Jared Isaacman as NASA administrator. He will become the agency’s 15th administrator since its founding in 1958. Isaacman, 42, made his fortune through the online payments company Shift4, which he founded at 16. He entered the space world in 2021 when he financed and commanded Inspiration4 – the first spaceflight crewed entirely by civilians without astronaut training. He and three crewmates spent three days orbiting Earth in a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft. He returned to space in 2024 as commander of Polaris Dawn, also flown in a SpaceX Dragon capsule, a private mission with a stronger scientific focus. The mission set several records, and during it Isaacman became the first private astronaut to conduct a spacewalk, exiting the spacecraft in a spacesuit.

After Donald Trump’s re-election as U.S. president late last year, Elon Musk—who played a key role in the new administration – backed Isaacman to lead NASA. The nomination raised an obvious conflict-of-interest concern: Isaacman is one of SpaceX’s major customers, and as NASA administrator he would be positioned to influence the flow of large federal budgets to private companies, including SpaceX. The conflict did not deter the president, but as relations with Musk cooled, Trump unexpectedly withdrew the nomination—when it was already close to approval—after learning that Isaacman had also donated to Democratic candidates. Five months later, Trump revived the nomination after all. This time, the process moved forward, and last Wednesday the Senate granted its approval.

Isaacman now takes charge of an agency with about 14,000 employees, which has faced sharp budget and staffing cuts in recent months. NASA is also at a strategic crossroads. The agency is pushing ahead with the Artemis program to return humans to the Moon, with the first crewed lunar flyby since 1972 scheduled for next year. Musk, however, has repeatedly argued that Mars – not the Moon – should be NASA’s primary destination. At the same time, the United States must contend with China’s effort to land astronauts on the Moon, potentially outpacing the U.S. in the current race. NASA is also preparing for the post–International Space Station era: the ISS is expected to be retired toward the end of the decade and likely replaced by private stations. Isaacman is an unusual choice by NASA’s historical standards, as administrators typically come from science and space or from politics. He enters the role with relatively broad support, but faces difficult tests—and Washington’s complex politics. After a year marked by acting leadership, most notably Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy, the agency is badly in need of stable, permanent direction.

Jared Isaacman will move from the role of private astronaut and tech entrepreneur to public service at the helm of the world’s largest space agency. Isaacman in a SpaceX spacesuit | Photo: Polaris Program / John Kraus

Closer Than Ever – and Astonishingly Far

The interstellar comet 3I/Atlas, first reported at the beginning of July this year, is making its closest approach to Earth this weekend as it passes through our Solar System. Even so, “close” is relative: on Friday it passed about 269 million kilometers away—much farther from us than the Sun is.

The object was discovered about half a year ago, and its speed and trajectory quickly revealed it to be a visitor from beyond the Solar System. It is only the third object ever identified as originating in another planetary system, which is why it was designated 3I/Atlas: “3” is its serial number, “I” stands for interstellar, and ATLAS is the name of the survey that first detected it. The intriguing newcomer soon became the target of extensive observations from ground- and space-based telescopes, and it was quickly confirmed to be a comet – an ice-rich body that warms as it nears the Sun, releasing gas and dust trapped in its ice. That outgassing produces the hazy coma around it and the long tail trailing behind.

By tracing its orbit and speed backward, researchers estimate that it formed even before our Solar System did. One scenario suggests that it was flung out of its home system after a close pass by a giant planet, whose gravity diverted it onto an interstellar journey lasting billions of years. Another possibility is that the comet was ejected from its system during the chaotic process of planet formation – much as researchers believe our own Solar System also hurled small bodies into interstellar space during its formative period.

Because the comet is so distant—and its coma so large—its true size is hard to pin down; diameter estimates range from about 400 meters to as much as six kilometers. Still, its closest pass this weekend gives many astronomers, professional and amateur alike, a chance to train telescopes on it and gather as much data as possible. The interstellar visitor is already heading out of the Solar System after reaching perihelion—the closest point to the Sun—in late October, passing about 200 million kilometers from it. Now it is rapidly receding from Earth as well, though it will take roughly another decade to complete its traverse of the Solar System and return to interstellar space.

An early Christmas gift for astronomers. Comet 3I/Atlas in a photo taken by the Hubble Space Telescope last month | Source: NASA, ESA, STScI, D. Jewitt (UCLA), M.-T. Hui (Shanghai Astronomical Observatory), J. DePasquale (STScI)

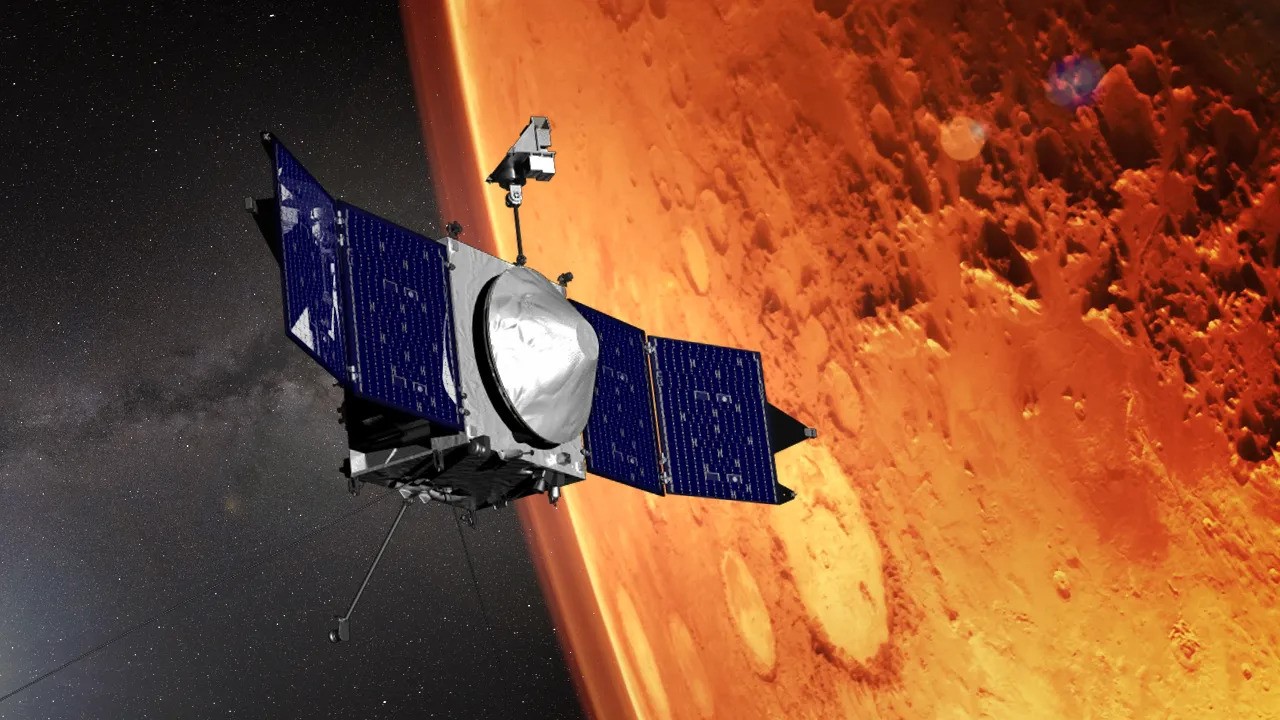

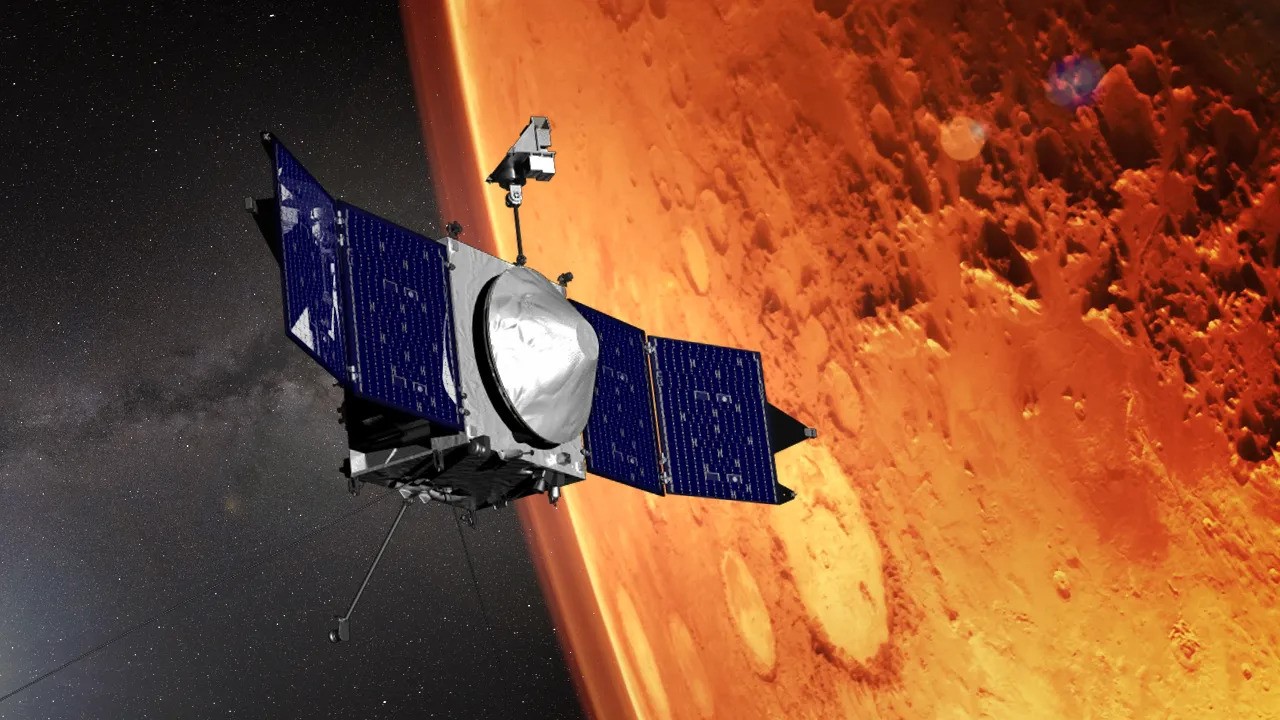

Lost Around Mars

NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft, which has been orbiting Mars for more than a decade, stopped communicating with controllers about two weeks ago, and this week new, troubling indications about its condition emerged. A detailed analysis of the last signals received from the aging orbiter suggests it has likely entered an uncontrolled spin in an unexpected direction – and may have drifted from its intended orbit as well. NASA has not addressed the possible causes. Such a deviation could be caused, for example, by a small onboard explosion, a leak, or an impact by an external object.

MAVEN—short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN—launched in 2013 to study the Red Planet’s atmosphere and entered Mars orbit in 2014. Originally designed for a one-year mission, it far outlasted its planned lifetime, returning a wealth of data on how Mars’ atmosphere interacts with charged particles from the Sun, as well as on dust storms and other atmospheric phenomena. MAVEN has also served as a communications relay between mission control and the surface rovers operating on Mars, including Curiosity and Perseverance.

NASA is continuing efforts to reestablish contact with the spacecraft. In its statement, the agency said that at the same time, control teams are also adjusting the orbits of other Mars satellites to help mitigate communications gaps and the effect of the MAVEN anomaly on surface operations for surface rovers on the planet.

Launched for a one-year mission and successfully operated for 11 years studying the atmosphere of the Red Planet. An illustration of the MAVEN spacecraft around Mars. Source: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

To the Edge of Space in a Wheelchair

Blue Origin, which operates tourist flights to the edge of space, launched on Saturday (December 20) the first person to fly while using a wheelchair. The passenger was Michaela “Michi” Benthaus, a 33-year-old German aeronautics and space engineer at the European Space Agency (ESA). In 2018, while still a student, she was injured in a cycling accident and left paralyzed from the waist down. She returned to her studies despite the injury and joined ESA last year. The original launch attempt was halted less than a minute before the end of the countdown to investigate an issue, and the flight was carried out on Saturday instead.

All six passengers on NS-37 have ties to the space world. The best known is aerospace engineer Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president until 2021. The other passengers were investors Adonis Pouroulis and Joey Hyde, entrepreneur Neil Milch, and space enthusiast Jason Stansell. The crew flew in a capsule launched atop a reusable New Shepard rocket from the company’s Texas spaceport. The rocket carried the capsule to just over 100 kilometers—commonly defined as the “edge of space”—before returning for a controlled vertical landing at the launch site. The passengers experienced a few minutes of weightlessness and sweeping views through the windows, then the capsule fell back to Earth and landed under parachutes not far from the launch area, for a total flight time of about 10–12 minutes.

The launch marked New Shepard’s 37th mission and Blue Origin’s 17th crewed flight. Across the first 16 crewed missions, 80 tourists flew to the edge of space, including six who flew twice.

About three years ago, ESA selected British doctor and leg amputee John McFall for its astronaut reserve, describing him as “the first astronaut with a disability.” McFall, a former Paralympic sprinter and medalist, was placed in the astronaut training program. However, because ESA does not operate its own crewed space missions, only a small number of European astronauts fly to the International Space Station, and he has not yet been assigned to a spaceflight.

A crew of space enthusiasts, including the first passenger paralyzed from the waist down. The space tourists of flight NS37 and the mission patch | Source: Blue Origin

The Double-Blast Cosmic Enigma

A supernova is a violent explosion that marks the end of life for certain stars—so enormous and bright that it can outshine an entire galaxy. In 2017, astrophysicists identified another kind of cosmic blast, produced by the collision and merger of two neutron stars orbiting one another. The phenomenon was dubbed a “kilonova,” and in the eight years since that first discovery… astronomers found exactly zero more of them – until this past August. In August, the gravitational-wave detectors LIGO in the United States and VIRGO in Italy recorded signals consistent with such an explosion. Following the alert, many astronomers quickly trained ground- and space-based telescopes on the source. In the first days, the transient looked like the 2017 kilonova. But three days later, it changed – its light and behavior began to resemble an ordinary supernova more than the long-sought kilonova.

Whereas a kilonova is characterized by a reddish glow, driven by the formation of heavy elements such as gold, platinum, and uranium, a supernova produces lighter elements like iron and carbon and is also characterized by the emission of large amounts of hydrogen – making its light much bluer. Adding to the puzzle was the gravitational-wave detection: supernovae do not generate such waves, and the signal analysis suggested that at least one of the two neutron stars involved was unusually small.

A large international team of researchers analyzed the strange findings, and in a paper published last week, proposed that the event may be a hybrid: a rapidly spinning star that first exploded as a supernova, producing a neutron star. They then suggest two possible explanations. One is that the neutron star split in two, with the smaller fragment rapidly orbiting the larger until the pair collided or merged. The other is that excess material from the supernova condensed into a small neutron star that later crashed into its larger sibling. In both cases, the result would be an event that begins as a supernova, transitions into a kilonova, and then—after the kilonova fades—appears supernova-like again. The researchers have dubbed the phenomenon a “superkilonova,” though they stress that the idea remains a hypothesis and that more such events will be needed to confirm it.

“Future kilonovae events may not look like GW170817 and may be mistaken for supernovae,” said the study’s lead author, Mansi Kasliwal of the California Institute of Technology. “We can look for new possibilities in data like this, but we do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova. The event, nevertheless, is eye opening.”

How it may have happened: a simulation of a superkilonova event that begins as a supernova, creates two neutron stars, and continues with their collision, producing a kilonova: