A Brief History of the Telescope

For thousands of years, humans gazed at the sky without understanding what lay behind the points of light above them. The invention of the telescope opened a window for humanity to distant worlds. But whom do we have to thank for the device that can transform a tiny speck in the night sky into a breathtaking image of Saturn?

26 November 2025

|

15 minutes

|

The ability to view distant objects in fine detail – as if they were close at hand – has served military commanders, seafarers, and astronomers throughout history. While magnifying instruments were once used primarily for military purposes, today’s telescopes expand our knowledge of the universe and allow us to study phenomena that cannot occur on Earth. Determining the composition of distant celestial bodies has greatly advanced our understanding of cosmic processes and has even contributed to the development of advanced technologies.

As the centuries passed, humanity’s ability to see not only farther but also with ever-increasing detail and clarity steadily improved—from magnifying the roof of a distant building or the outline of a distant ship to observing celestial bodies hundreds of light-years away in high-resolution detail, allowing us to explore the depths of space. All of this became possible thanks to several individuals throughout history, each of whom managed to “see far,” both literally and figuratively, laying one after another the foundations that ultimately led to the development of the modern telescope.

As the centuries passed, humanity’s ability to see farther and with greater detail and quality steadily improved. An engraving by Adriaen van de Venne depicting the “Dutch telescope,” 1624 | Wikimedia, Pieter Kuiper.

The Dutch Lens Grinders

It is difficult to determine with certainty who first invented the telescope, as it appears to have been developed almost simultaneously by several inventors who were unaware of one another’s work. Although many credit the invention to the great Italian scientist Galileo Galilei, the earliest version likely originated in the Netherlands.

Legend has it that the children of Hans Lippershey (Lipperhey), a Dutch lens grinder, were playing with several defective lenses in their father’s workshop when they discovered that the roof of a distant building appeared magnified. In 1608, Lippershey submitted a patent application to the Dutch government for an optical device he had created, consisting of two lenses that allowed distant objects to be viewed at tenfold magnification.

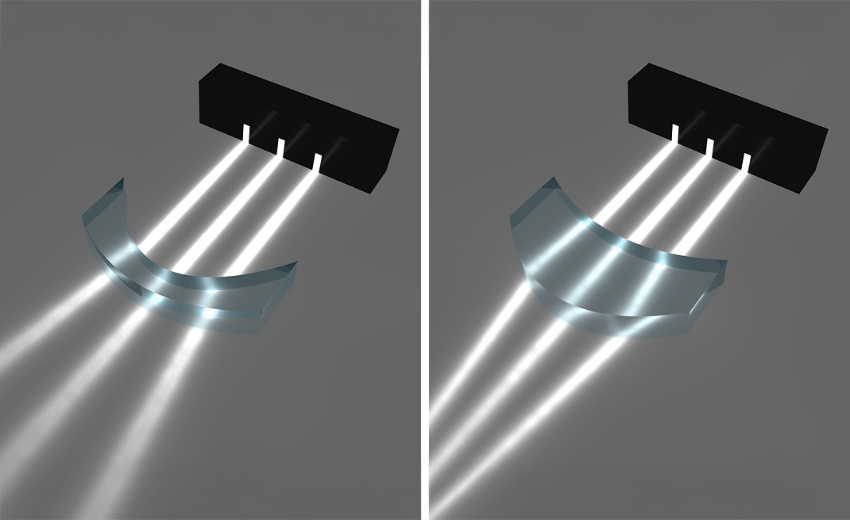

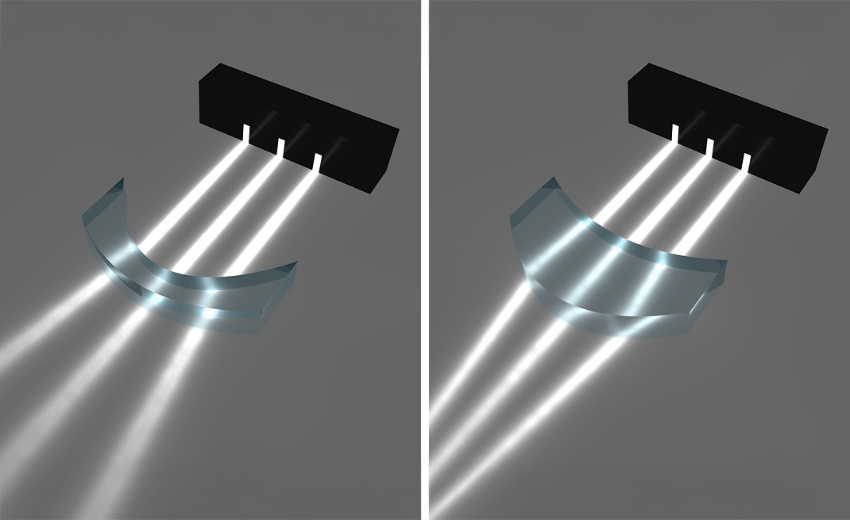

As a lens maker, Lippershey was well acquainted with the optical properties of lenses and relied on their ability to focus and disperse incoming light. A convex lens (shaped like a dome) focuses light rays, while a concave lens (shaped like a bowl) spreads them out. Although it is unclear who first recognized that positioning two such lenses at the proper distance produces a magnified image, Lippershey transformed this principle into a functional instrument. His patent request, however, was not approved, as similar applications had been submitted around the same time by eyeglass makers Jacob Metius and Zacharias Janssen – one of the early inventors of the microscope. Moreover, there was no practical way to protect or keep the patent secret.

The description of Lippershey’s invention spread throughout Europe, where wealthy individuals used it primarily as an optical amusement—until the news reached Italy, home to a scientist named Galileo Galilei.

Lippershey made use of the ability of lenses to focus or disperse incoming light. A convex lens (right) focuses light rays, while a concave lens (left) disperses them. | Russell Kightley / Science Photo Library.

Bending the Light

The telescope (from the Greek tele τῆλε — “far,” and skopein σκοπεῖν — “to see”) created by Lippershey was a refracting telescope. This type of instrument relies on bending light through a system of lenses, including one that focuses the light into the viewer’s eye at the back of the device. In 1609, news of the telescope’s invention reached Galileo Galilei, who had already earned a reputation as a respected scientist. Galileo did not settle for merely obtaining a telescope – he built an improved version and significantly increased its magnification power, achieving twentyfold magnification. Yet his true greatness lay not in the engineering of the device but in how he chose to use it: Galileo was perhaps the first to turn a telescope toward the night sky and uncover entirely new findings about the Moon and the planets. For this reason, many mistakenly believe he invented the device.

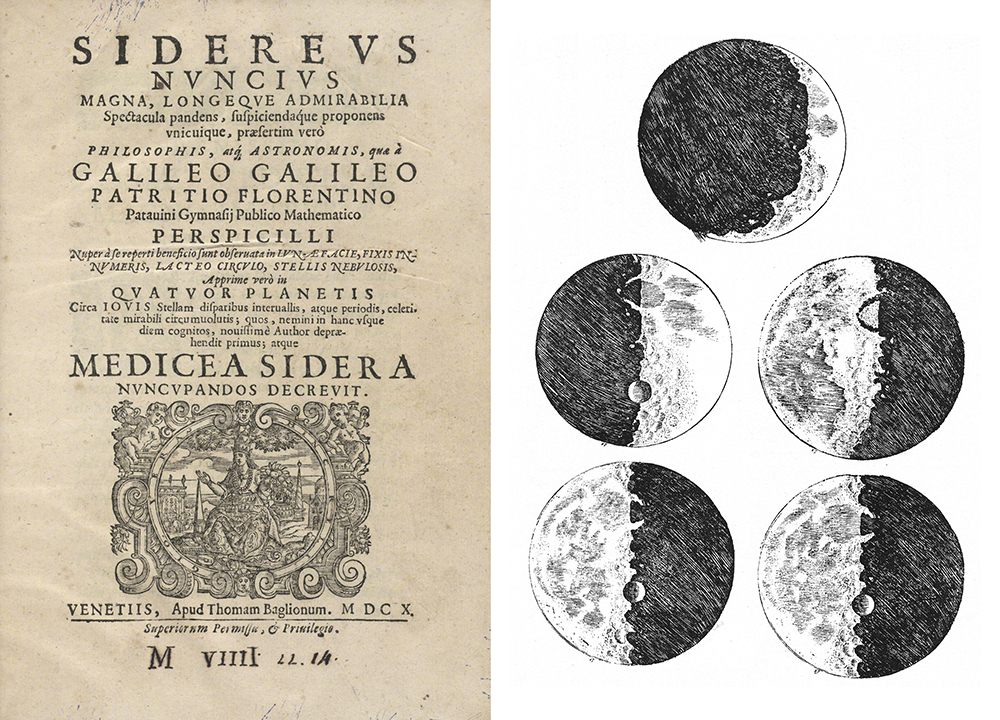

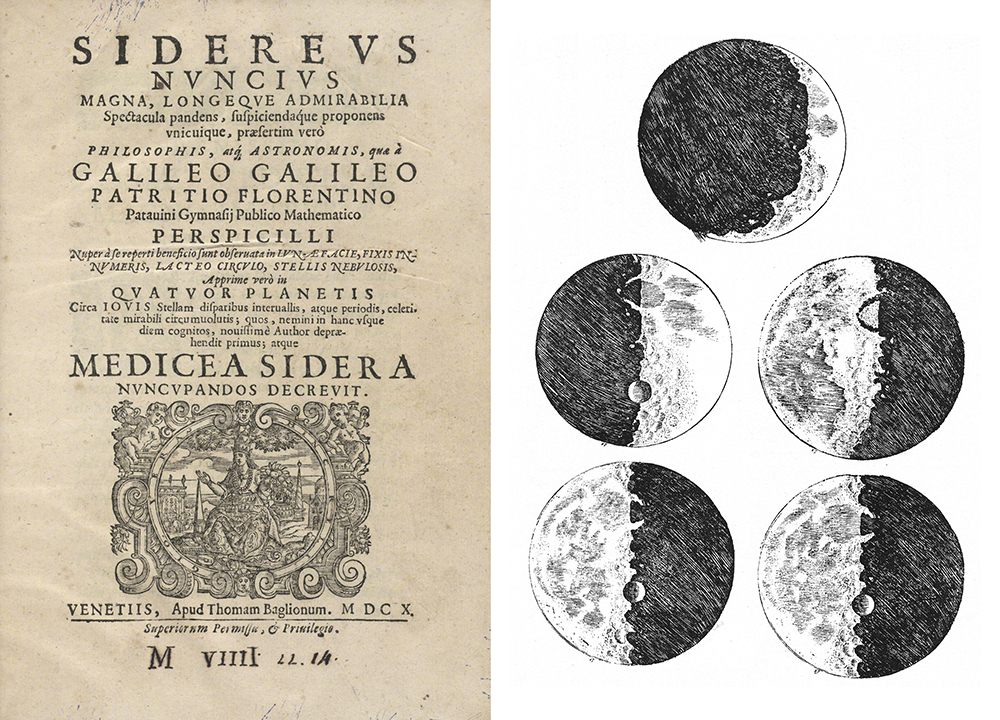

Galileo’s first major discovery made possible by the telescope was his description of the Moon’s surface. Before his observations, the Moon—like other celestial bodies—was widely regarded as a perfectly smooth, flawless sphere. Through the telescope, however, Galileo revealed that the Moon’s surface is marked by valleys, mountains, and craters. After studying the Moon, Galileo turned his attention to Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system. He observed three previously unknown celestial bodies near the planet, and three nights later noticed that one had disappeared. He correctly concluded that it had moved behind Jupiter. Galileo soon realized that these objects were moons orbiting the planet, and he later identified a fourth. Today, these four largest Jovian moons are known as the Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Galileo’s first major telescope-enabled discovery was his detailed description of the Moon’s surface. The title page of Galileo’s first astronomical treatise, shown alongside his accompanying sketches of the Moon | Wikimedia, Grook Da Oger, Rob at Houghton.

The discovery of Jupiter’s moons was not only an impressive demonstration of the telescope’s power but also a significant challenge to the geocentric worldview. For centuries, people had accepted the model proposed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, which placed Earth at the center of the universe. Only a few decades before Galileo, astronomers—led by Copernicus—began questioning this long-standing model. Copernicus’s revolutionary claim that the Sun, not Earth, lies at the center of the cosmos paved the way for later astronomers, including Galileo, who essentially confirmed Copernicus’s ideas using the telescope. Galileo’s discovery that moons orbit Jupiter offered compelling evidence that not all celestial bodies revolve around Earth.

Around the same time, Galileo discovered that, contrary to previous belief, Venus exhibits a full set of phases—from crescent to full—much like the Moon. He also identified Saturn’s rings and observed sunspots on the surface of the Sun. Galileo published his findings on sunspots in a pamphlet titled Letters on Sunspots (Istoria e Dimostrazioni intorno alle Macchie Solari), which included his own illustrations crafted to persuade readers of the validity of his groundbreaking observations.

Galileo also discovered Saturn’s rings and sunspots. A painting by Giuseppe Bertini depicting Galileo presenting the telescope to the Venetian nobility | Wikimedia, David J Wilson.

The Man Behind the Lens

Many great minds helped shape the telescope as we know it today, among them the English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton. Until Newton’s time, telescopes were built solely from lenses. But in 1666, he discovered that light rays could be brought to a single focus not only with a lens but also with a concave mirror that reflects light to a common focal point. In the telescopes Newton designed, a concave mirror at the rear of the instrument reflects light to a focal point near the front. By using a mirror, Newton overcame a major problem inherent in refracting telescopes: their focusing lens bends light of different colors by different amounts, making it impossible to bring all colors to the same focus. This optical flaw, known as chromatic aberration, caused Galileo’s telescope to produce a slightly blurred image.

The mirror solved this problem because it reflects all colors of light in the same way. The reflecting telescope has additional advantages, most of them arising from the size of its mirror, which can provide greater magnification than a lens. A large mirror is also easier to build, since polishing a lens requires far greater precision than shaping a reflective surface. Today, most telescopes are constructed using the technology Newton pioneered.

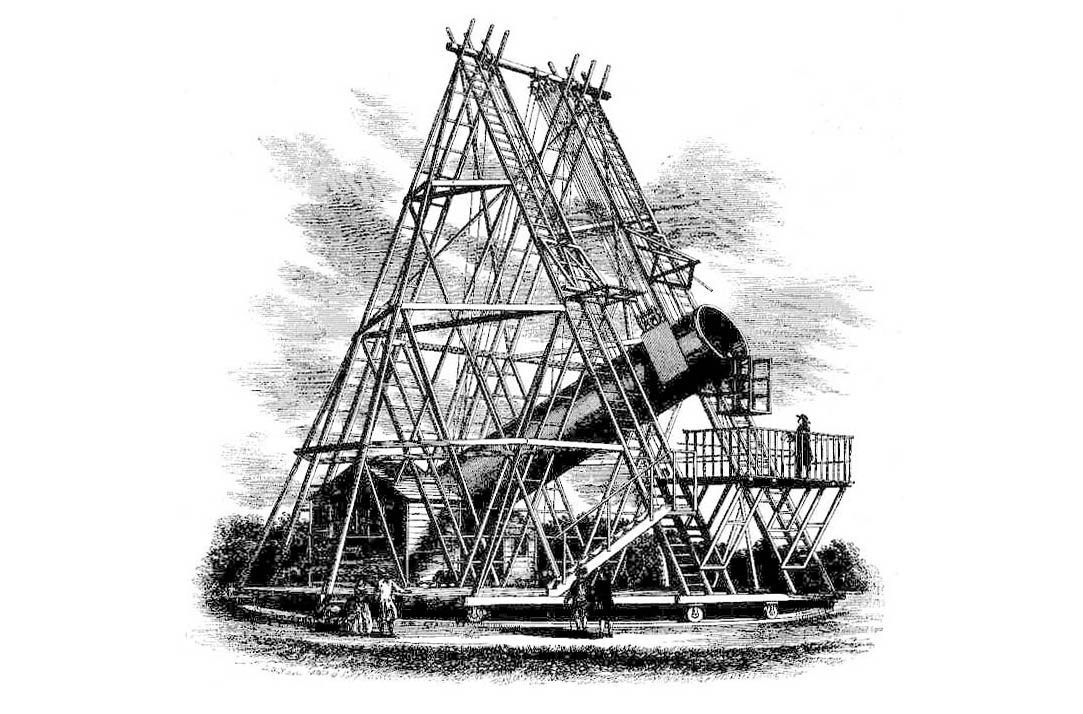

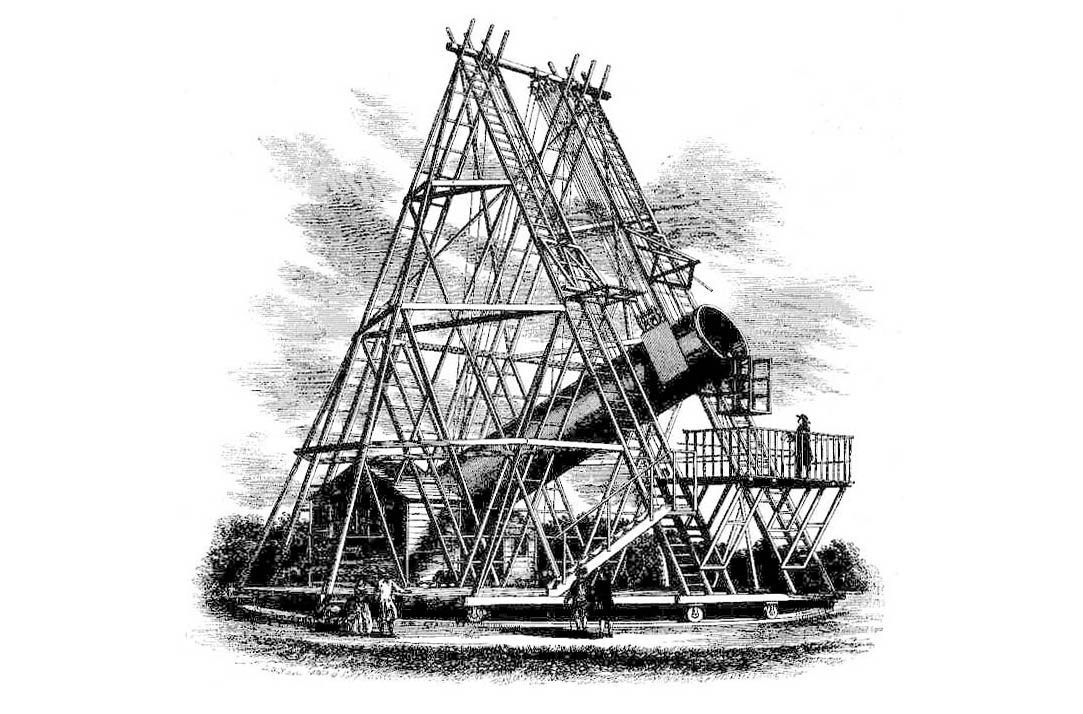

William Herschel’s most famous creation was a 12-meter-long telescope, the largest of its time, which held that distinction for 50 years. Illustration of the telescope | Wikimedia, ArtMechanic.

Dreaming Big

The physicist and astronomer William Herschel was born on November 15, 1738, in Hanover, Germany. As a young man, he immersed himself in physics books and soon developed an interest in telescope construction, lens grinding, and astronomical observation. He built his own telescope and began studying the sky, focusing on the Moon and on double-star systems—pairs of stars that orbit one another. Herschel was the first person to observe the planet Uranus through a telescope. At first he believed it to be a comet, a small celestial body composed largely of ice, but further observations and calculations by scientists across Europe revealed that it was in fact a planet moving in an elliptical orbit around the Sun.

Alongside his observations, Herschel built roughly 400 telescopes, many of which he sold to astronomers. His most famous creation was a 12-meter-long telescope, the largest of its time, a record it held for 50 years. Designed and constructed over the course of four years, it was inaugurated in 1789. In that same year, Herschel used it to discover two of Saturn’s moons. He later discovered Oberon, one of Uranus’s moons, and studied various other celestial bodies, coining the term asteroid (“star-like” in Greek). Years later, the telescope was dismantled by Herschel’s son, as it was on the verge of collapse. Parts of the instrument are now displayed at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, near London.

A Beginner’s Guide to Stargazing

In recent years, interest in home telescopes has steadily grown. Thanks to technological advances, many people can now afford instruments based on the same principles as Galileo’s refracting telescope and Newton’s reflecting telescope—and some modern models even combine both. Each type has its advantages and disadvantages: a refracting telescope is lightweight and easy to use, but it is often more expensive and bulkier, and the refraction of light can cause slight image blurring. A reflecting telescope is generally cheaper and more compact because it uses a mirror, but it can be more challenging to maintain.

Anyone considering the purchase of a telescope is advised to attend astronomical observation events, explore different instruments, and learn about their capabilities in order to determine which type best suits their needs. It is important to remember that home telescopes cannot produce images comparable in quality to those from the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes, but they still offer impressive and beautiful views of relatively nearby celestial objects such as the Moon, Saturn, and Jupiter.

Radio Trek

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, new types of radiation—microwave radiation and radio waves—were discovered, opening up entirely new ways to study the universe that were no longer based solely on visible light. Many sources of microwave and radio radiation exist throughout the cosmos. The cosmic microwave background (CMB), for instance, provides a glimpse into processes that occurred close to the universe’s earliest moments. Galaxies, too, are strong emitters of radio waves, generated by the supermassive black holes at their centers as they consume vast amounts of infalling matter. As a result, radio and microwave radiation constitute extremely valuable tools for astrophysicists, and the variety of telescopes designed to detect them is especially large.

Radio and microwave telescopes are usually divided into two main types. High-frequency telescopes use concave dishes to focus incoming radiation, functioning much like the mirrors in reflecting telescopes. Low-frequency telescopes rely on arrays of antennas spread across large areas and arranged to amplify signals arriving from a specific direction. These arrays are typically designed so their viewing direction can be adjusted with relative ease. When many small radio or microwave telescopes are positioned correctly and their signals combined, the resulting data achieve extremely high resolution—as if they were collected by a single, much larger telescope.

One of the most famous images produced using such a system is the first-ever image of a black hole, captured in 2019.

Radio and microwave radiation are invaluable tools for astrophysicists, and accordingly the range of radio and microwave telescopes is especially broad. A radio telescope in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Spain | Shutterstock, fornaxstock.

The Next Generation of Telescopes

Observing stars and planets from the ground has produced remarkable discoveries, but humanity continually strives to reach even farther. Many of the latest telescopes are placed in space, enabling them to overcome the distortions caused by Earth’s atmosphere: as light passes through the atmosphere, it bends (the reason stars appear to twinkle), and unstable airflows bend it even more, making it difficult to focus. Telescopes operating in space avoid these issues entirely, resulting in significantly sharper and more detailed images.

The most famous space telescope is likely the Hubble Space Telescope, named after the astronomer Edwin Hubble – though it was preceded by several telescopes launched into space by the United States and the Soviet Union. Hubble was launched into Earth orbit in 1990 aboard NASA’s Space Shuttle Discovery. It was equipped with a 2.4-meter mirror that took two years to polish and, for the first time, provided high-quality images of distant celestial objects. Beyond its position outside Earth’s atmosphere, Hubble’s distinctiveness lies in its ability to detect radiation in visible light, ultraviolet light, and the higher-frequency ranges of infrared radiation. Like Newton’s telescope, it relies on mirrors to observe distant objects—an approach that allows for extremely precise measurements unattainable by other methods. Hubble is considered one of the most important instruments in the history of space exploration, and its spectacular images have become famous worldwide. Among its many achievements, it helped determine the accelerating expansion rate of the universe, produced new images of galaxies in the early universe, and provided insights into processes such as galaxy collisions, star formation, planetary system formation, supernovae, and more.

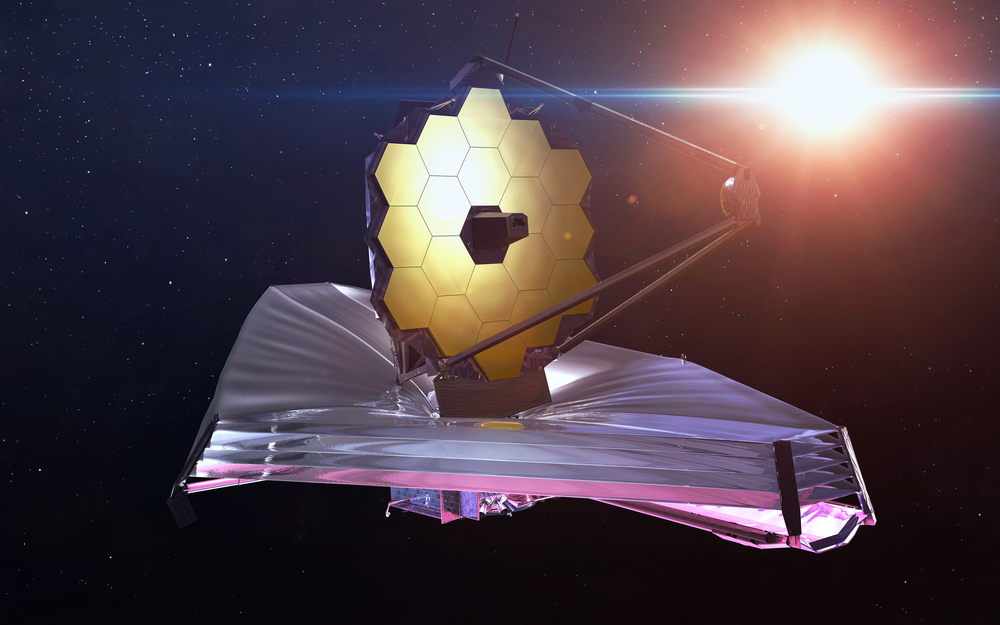

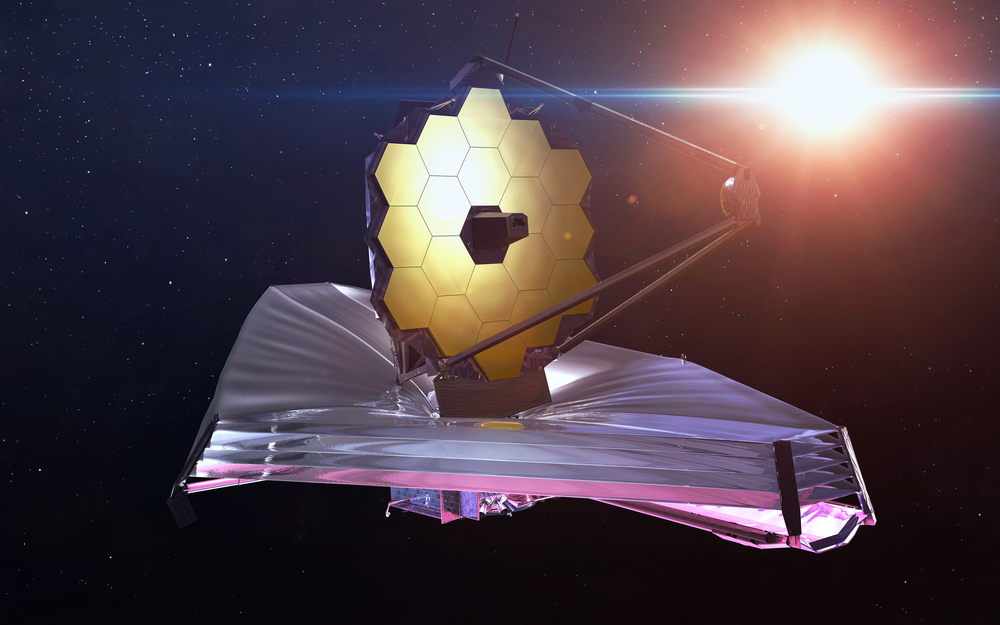

After Hubble’s tremendous success, NASA decided to take space telescopes a step further. Illustration of the James Webb Space Telescope | Shutterstock, Vadim Sadovski

After Hubble’s enormous success, NASA set out to advance space telescopes even further, spending 20 years developing the powerful James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021. Webb is an optical telescope that detects visible light mainly in the red range, as well as nearby infrared wavelengths, using a giant 6.5-meter mirror. Its primary mirror is composed of 18 hexagonal beryllium segments coated with a thin layer of gold, which reflects red and infrared light exceptionally well. The combination of this large mirror and its sensitivity to these wavelengths allows astronomers to peer far deeper into the early universe in an effort to understand how the first galaxies formed. Because light takes time to reach us, the farther away a galaxy is, the earlier the moment at which the light we see began its journey—meaning we observe it as it appeared long ago. Yet the more distant a galaxy is, the fainter its light becomes by the time it arrives. Thanks to Webb’s enormous mirror, even these extremely distant objects can now be studied.

While Hubble and James Webb continue to glide through space, researchers on Earth have not paused for a moment and are already developing the next generation of telescopes. One such project—led by the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Israel Space Agency – is ULTRASAT, intended to be Israel’s first space telescope. Planned for launch in 2027, it is designed to detect ultraviolet light, as its name suggests.

Meanwhile, NASA is working on its next mission: the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in 2026 aboard SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket. First proposed in 2010 as a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, it was named in 2020 after Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first chief astronomer, known as the “Mother of Hubble.” The Nancy Grace Roman Telescope is similar to Hubble and will also capture images in visible and infrared light.

From a pair of simple lenses in the 17th century to powerful telescopes roaming through space in the 21st, humanity’s ability to peer beyond the atmosphere into new and distant worlds has advanced steadily. No one knows where the future will take us—but one thing is certain: the sky is no longer the limit.