The Moss That Survived in Space: This Week in Space

A new crew arrived at the International Space Station, China restores its escape-capable spacecraft, a Starship test ends in an accident, South Korea achieves a milestone launch and moss biology delivers surprising results in space. This Week in Space

3 December 2025

|

8 minutes

|

New Crew

Three new crew members arrived at the International Space Station last Thursday. American astronaut Chris Williams and Russian cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov and Sergey Mikaev lifted off aboard a Soyuz spacecraft from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Barely three hours later, the spacecraft docked with the station’s Russian segment, adding the trio to Expedition 73. Their mission will continue into next year as part of Expedition 74, with a total stay of about eight months planned on the station in total..

They take the place of Russian cosmonauts Sergey Ryzhikov and Alexei Zubritsky, as well as American astronaut Jonny Kim, who have been aboard since April. After a short handover, the three will return to Earth in early December. Before they depart, the enlarged crew—which now also includes two additional Americans, another Russian, and a Japanese astronaut—will celebrate Thanksgiving together, enjoying both pre-positioned holiday meals sent months in advance and fresh supplies delivered with the newly arrived crew.

Launch of the Soyuz MS-28 spacecraft to the International Space Station, 27 November 2025.

The Rescue Vehicle Arrived Safely

China successfully launched an uncrewed rescue spacecraft to its space station, ensuring that astronauts can be evacuated in an emergency after they were left without an escape vehicle. The uncrewed spacecraft docked with the Tiangong space station last Monday, delivering substantial supplies for the crew currently aboard.

The station’s current crew—Zhang Lu, Wu Fei, and Zhang Hongzhang—arrived on 31 October as part of the Shenzhou-21 mission. The previous crew, from Shenzhou-20, was expected to return to Earth after a brief handover. However, the China Manned Space Agency delayed their return after a crack was discovered in the window of their spacecraft, likely caused by the impact of a tiny piece of space debris. The crew eventually returned to Earth three weeks ago aboard Shenzhou-21, leaving the new crew on the station without an escape vehicle in the event of damage or an emergency requiring evacuation.

In response, the agency initiated an accelerated preparation process for the Shenzhou-22 spacecraft, originally intended to bring the next crew to the station in spring 2026.“The mission directorate smoothly activated the emergency plan, and research and experiment units cooperated to overcome the challenges,” the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) said in a statement. Preparing the spacecraft so quickly, they added, “was a successful example of an effective emergency response in the international space industry.”

This type of malfunction is not unique to China. In 2023, fuel leaks were detected in two Russian spacecraft docked to the International Space Station—one cargo craft and one crew vehicle—forcing Russia to send a replacement spacecraft and return the leaking one to Earth uncrewed. Those incidents were also believed to have been caused by impacts from space debris. China now plans a similar uncrewed return of its damaged spacecraft. If the landing is successful, engineering teams will investigate the source of the impact and consider design improvements to reduce the risk of similar damage in the future.

It remains uncertain whether China will be able to ready another spacecraft in time to launch the next crew as planned in April or May 2026. However, this does not necessarily mean the current crew’s mission would need to be extended. The station can operate uncrewed for several weeks or even months while awaiting the next arrival. Still, China may prefer not to interrupt the station’s continuous human presence, maintained since 2021. In any case, the incident underscores the growing risk posed by space debris in low Earth orbit and the urgent need to address it—not only to protect crewed missions but also to safeguard the space-based technological infrastructure.

Providing the station’s crew with a renewed escape option. The Shenzhou-22 spacecraft gliding into automatic docking with China’s Tiangong space station last week. | Photo: China Manned Space Agency

Starting With an Explosion

SpaceX is pressing ahead with development of its Starship system. After completing tests the company has begun preparing for the first launch of the third-generation Starship spacecraft and booster. Those preparations, however, began with an accident during an early test of the first rocket to roll off the production line. “Booster 18” was set up for its initial test campaign at the Massey test facility—SpaceX’s experimental site near its South Texas spaceport.These early tests were designed to evaluate updates to the rocket’s fuel-flow system and the mechanical strength of the new version of the rocket, which is roughly a meter taller than its predecessor. Shortly after the test began on November 21st, an explosion occurred in the rocket’s lower section. In at least one respect—its mechanical resilience—the rocket proved itself, remaining upright on the stand despite the blast.

The company later reported that the explosion occurred during gas system pressure testing conducted in advance of structural proof testing, and that no propellant was on the vehicle and engines were not yet installed. They also emphasized that no one was injured.

Despite the malfunction, SpaceX says it intends to meet the planned timeline for testing the third-generation Starship. In a company tweet, they stated that they aim to have the next Super Heavy booster stacked in December, and that the first test launch of the first Starship V3 vehicle is scheduled for the first quarter of 2026.

Testing of the Starship system began about two and a half years ago, and although progress has been substantial, the company remains behind its original schedule. The spacecraft has yet to complete an orbital flight or attempt in-space refueling—one of the essential milestones for enabling Starship’s long-term role as a crewed lunar lander for NASA’s Artemis program, and later for Mars missions envisioned by founder Elon Musk. According to the planned timeline, a Starship spacecraft is expected to land humans on the Moon before the end of 2028—a target that already seemed highly ambitious even before the recent accident.

How it looked before the explosion. Booster 18 being placed on the Massey test stand ahead of its first tests last Friday | Photo: SpaceX

A Success for South Korea

South Korea launched its largest satellite to date this week aboard a domestically produced Nuri rocket. The satellite, CAS500-3, with a launch mass of about 516 kilograms, is a scientific satellite designed to study Earth’s atmosphere using cameras and instruments that measure plasma and magnetic fields. It will also carry out several life-science experiments, including research on stem-cell development in microgravity and the printing of biological tissues in space. The satellite was launched on Wednesday night from the Naro Space Center in the south of the country, and along with it, 12 tiny research satellites from Korean universities and research institutes were placed into orbit. The satellite successfully entered its orbit, at an altitude of about 600 kilometers, and deployed its solar panels.

This was the fourth launch of the Nuri rocket, a three-stage rocket developed by South Korea and first launched in 2021. What’s new in this launch is that the rocket was assembled by a private company, Hanwha Aerospace, under a technology transfer agreement from the Korean national space agency, transferring to it technology developed by the Korea Aerospace Research Institute. Two more launches of this rocket are planned over the next two years. “Building on today’s success, we will steadfastly pursue the development of next-generation launch vehicles, lunar exploration and deep-space missions,” said South Korea’s Science Minister, Kyung-hoon Bae.

Launch of the satellites aboard South Korea’s Nuri rocket, 26 November 2025:

The Moss That Survived in Space

Mosses are simple, non-vascular plants that inhabit almost every environment on Earth—from the peaks of the Himalayas to scorching deserts like Death Valley in California. Now it appears that even Earth’s harshest environments pale in comparison to their survival abilities: Japanese researchers succeeded in germinating moss spores that spent an extended period outside the International Space Station, where they endured extreme temperatures, the vacuum of space, microgravity, and intense radiation.

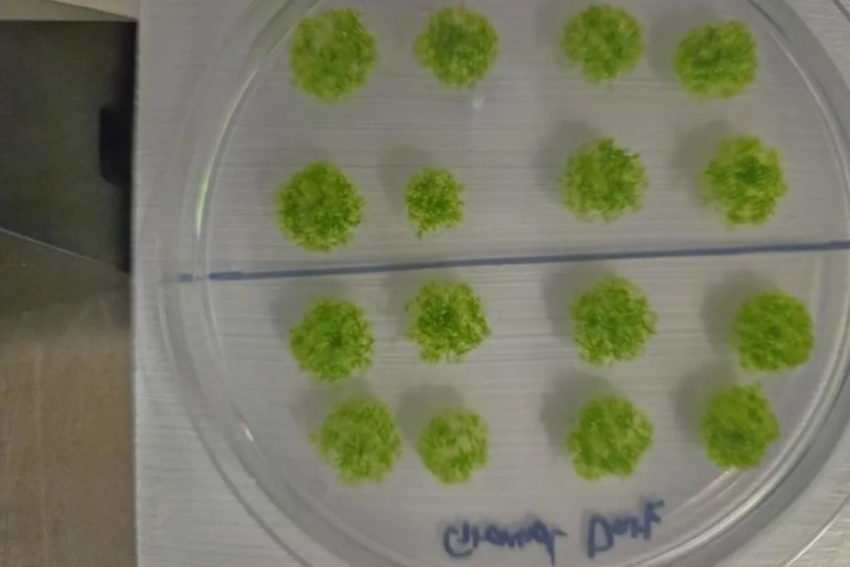

The research team, led by scientists from Hokkaido University, selected mosses of the species Physcomitrium patens and sent their spores (sporophytes)—the resilient stage in their life cycle adapted to withstand harsh conditions—to the space station. In 2022, the spores were placed in a special facility on the exterior of Kibo, the station’s Japanese laboratory module. The spores were divided into several groups differing in light exposure: some were sealed in opaque containers and kept in complete darkness; others were placed in transparent containers; and a third group was placed in transparent containers fitted with ultraviolet filters. After nine months, the spores were brought back into the station and then returned to Earth, where researchers tested their survival and attempted to germinate them.

More than 80 percent of the spores that spent time in space later germinated successfully in a Japanese laboratory. In a paper published two weeks ago, the researchers reported that survival rates were highest among spores kept in darkness (97 percent) and those exposed to light filtered of ultraviolet radiation (also 97 percent). Spores exposed to unfiltered ultraviolet radiation had a lower—but still impressive—survival rate of about 86 percent. However, not all surviving spores managed to germinate, and among those that did, some displayed damage such as reduced chlorophyll levels, which affected their development and function.

The researchers believe the spongy structure of the spores’ outer casing helped them withstand radiation and avoid desiccation in space. Based on the results, they estimate that such spores could survive up to 15 years under space conditions.

The experiment not only highlights the remarkable hardiness of moss but may also mark a step toward developing biological systems for long-duration space missions or for use on distant destinations such as the Moon and Mars. Understanding the biochemical and genetic mechanisms that give mosses their resilience could enable the engineering of more robust plants—valuable both in space exploration and on an increasingly warming Earth. It may even lead to plants that can be grown, or at least stored, on other planetary bodies. “The spores’ success in space could offer a biological stepping stone for building ecosystems beyond our planet,” said study lead author, Tomomichi Fujita.

Survived extremely harsh conditions. Spores germinated in the laboratory after returning from prolonged exposure to space conditions | Photo: Dr. Chang-hyun Maeng and Maika Kobayashi, CC BY-SA