Promises for the Future, Neglect of the Present: COP30 in Review

COP30 in Brazil ended with a troubling rollback of earlier commitments to phase out fossil fuels, alongside pledges of massive aid for countries hit hardest by climate change — but only starting a decade from now

15 December 2025

|

9 minutes

|

The UN’s 30th climate conference (COP30) in Belém, Brazil, which recently came to a close, dubbed “the Amazon COP”—opened with heads of state and government attending the first two days – the High-Level Segment. After that, several more days followed, during which professional teams continued the grueling negotiations.

The conference was supposed to be the turning point at which the world stopped talking and started acting to save “the lungs of the planet.” Instead, as delegates packed their bags—some rushing to leave after, in a somewhat ironic twist, a fire that broke out at the conference venue nearly shut down the discussions—the feeling left hanging in the air was a familiar, bitter mix: technical progress alongside a resounding moral failure.

Achievements: Big Money (at Last?) for the Forests

If there is one bright spot from the Belém conference, it is the official launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, succeeded where many have failed: creating a global financial mechanism that rewards countries not only for stopping deforestation, but also for preserving forests in the first place. With an initial raise of $6.7 billion and backing from 53 countries, this is a critical step toward saving tropical forests.

In addition, an agreement was reached on the “Belém Package”, which set a new financial target: $1.3 trillion per year to be transferred to developing countries—but implementation will begin only in 2035. The funding sources are a blend of government grants from developed countries, concessional loans from development banks such as the World Bank, and large-scale mobilization of private capital, alongside new taxation on polluting sectors such as shipping and aviation.

The conference also decided to triple funding for climate adaptation. It also established a new Just Transition mechanism, intended to ensure reskilling, strengthen social safety nets, and provide compensation for workers and communities that currently depend on the coal, oil, and gas industries—so they aren’t pushed into poverty as polluting facilities shut down.

Big money is supposed to arrive—but only in a decade. It’s not clear that this won’t be too late. COP30 climate conference discussions | Photo: Antonio Scorza, Shutterstock

The Big Miss: The Deafening Silence Around Fossil Fuels

Yet history will judge COP30 harshly for what it didn’t contain. Two years after the pledge at COP28 in Dubai to “transition away,” the final text adopted in Brazil represented a troubling retreat. The diplomatic battle centered on the words “phase-out” (a complete end) versus “phase-down” (a reduction). Under heavy pressure from oil-producing states—led by the Arab group—and amid opposition from major powers such as China, all binding language committing to a full end to the use of coal, oil, and gas dropped, leaving the text deliberately vague.

Despite the conference being held in the heart of the Amazon Basin, leaders also failed to agree on a binding global “roadmap” to end deforestation, settling instead for voluntary declarations. For scientists who have warned that we are nearing the ecosystem’s point of no return, the outcome felt like a bitter dismissal.

Negotiators failed to agree on binding steps to end deforestation. Delegates in traditional dress at the climate conference | Photo: Kenny Garcia and Aljun Alvarez for the Climate Champions Team

Criticism: Petty Politics in a Massive Disaster

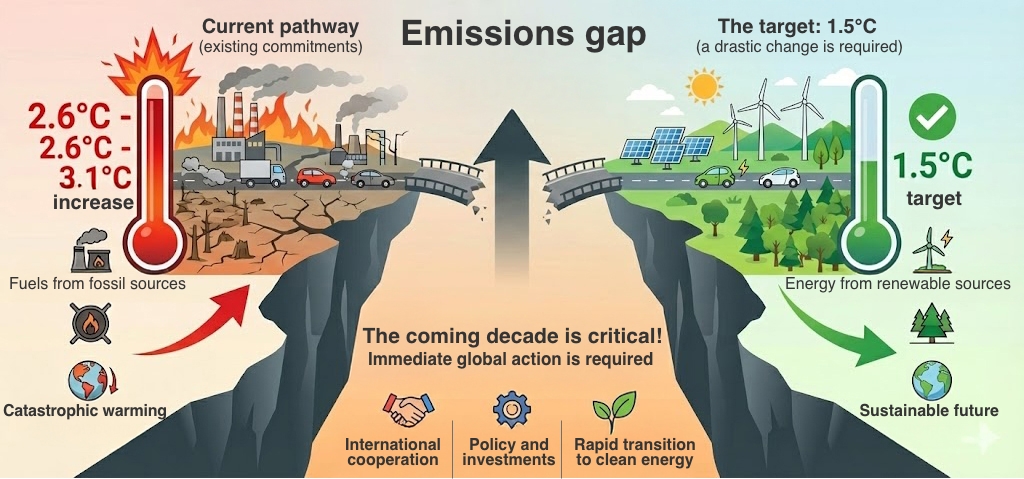

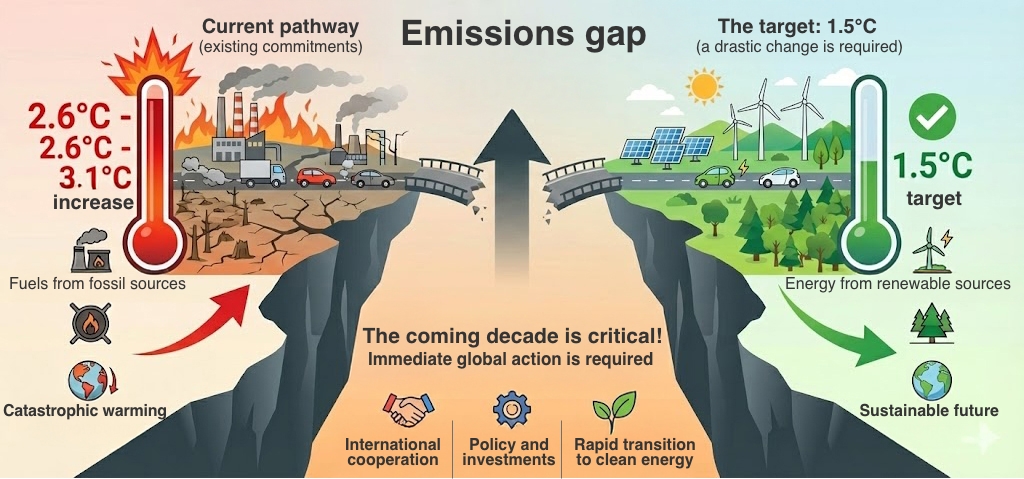

It’s hard not to point an accusing finger at the leaders who sat in air-conditioned rooms in Belém. Outside, the world is on track for warming at a pace of 2.5°C—according to an analysis of the latest NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) submitted this year. NDCs are the action plans each country submits to the UN every five years, detailing its targets for reducing carbon emissions. Taken together, they paint a clear picture: current pledges are not sufficient to keep warming within 1.5–2°C above the pre-industrial average, in line with the goal set at the Paris conference about a decade ago.

Likewise, the decision to delay meaningful financing until 2035 is dangerous for small island states such as Tuvalu, the Maldives, and Kiribati, which already face a real risk of flooding—along with saltwater intrusion into groundwater and the loss of habitable land due to rising sea levels.

Some island nations are already at risk of flooding. Satellite image of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean | Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

The United States was officially absent from COP30 for the first time in 30 years, after the Trump administration dismantled the climate negotiating team, reduced UN funding, and announced that no federal delegation would be sent to Belém. Into that vacuum stepped delegations from U.S. states and cities, along with American civil-society organizations, trying to send the message that “the United States is still in the game”—but without the authority to make official decisions.

The gap between the dramatic rhetoric of the opening speeches and the reality on the ground was impossible to ignore. UN Secretary-General António Guterres addressed the conference’s importance a week before it began, saying: “[Such a situation] could push ecosystems past irreversible tipping points, expose billions to unlivable conditions, and amplify threats to peace and security. Every fraction of a degree means more hunger, displacement, and loss – especially for those least responsible. This is moral failure – and deadly negligence..” Later in the conference he added: “We are down to the wire, and the world is watching Belém.. Communities on the frontlines are watching too – counting flooded homes, failed harvests, lost livelihoods… And asking: how much more must we suffer?”

And yet, by the end of the conference, we were left with cumbersome legal texts that lacked real force. Once again, politicians chose immediate political comfort over the courage the moment demands.

At the current pace, we are not on track to meet the goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C | Illustration: Liat Peli via Gemini

And Still — Cautious Optimism

Despite the disappointment, COP30 showed that the multilateral process is still alive. The fact that 122 countries submitted new climate plans indicates the issue has not fallen off the agenda.The failure to reach consensus led to the emergence of “coalitions of the willing”: countries such as Colombia and Brazil announced they would advance independent roadmaps to reduce – and ultimately move away from – fossil fuels.

Broad protests, meanwhile, underscored that the public is demanding that leaders follow through on the issues being debated, in hopes of amplifying key messages and drawing sustained media attention. During the conference, demonstrations and marches took place in Belém both outside the official venue and inside secured conference areas. Thousands of activists from climate organizations, youth movements, and local communities took to the streets with messages opposing fossil fuels and calling to protect the Amazon rainforest and Indigenous rights.

Indigenous protest groups from the Amazon region were especially prominent, carrying slogans such as “No Amazon, No Paris” and demanding that resources be transferred directly to the communities that actually protect the rainforest. At the same time, international coalitions held “people’s assemblies” outside the conference, arguing that the emerging texts were too weak—particularly in the absence of an explicit commitment to phase out fossil fuels.

Many took to the streets. Seventy thousand marchers joined a protest in Belém during the conference, calling for more decisive action to protect the environment | Photo: Hellen Loures/Cimi

Another bright spot was the strengthened standing of civil society, led by Indigenous Peoples. Representatives from organizations such as COICA (the umbrella organization of Indigenous peoples of the Amazon Basin) and Brazil’s APIB came to Belém not only as observers, but as participants at the discussion table. For the first time, it was promised that part of the TFFF forest-fund money would be transferred directly to Indigenous communities that manage the forests in practice—recognizing their traditional knowledge as a critical tool in the fight against the climate crisis.

In conclusion, the smoke that rose above the convention center in Belém may have cleared, but the activists’ fire only grew stronger. The road to COP31 in Antalya, Turkey, has already begun. Over the coming year, attention will focus on whether the new financing mechanisms actually start moving money, and whether the “coalitions of the willing” can build momentum that bypasses political paralysis. The challenge in Antalya will be to turn Belém’s financial promises into practical work plans in cities and industries around the world.