Going Open Access in Scientific Publishing

A series of far-reaching steps by governments, research organizations, and even investment funds is expected to significantly expand the number of scientific publications freely accessible to the public.

2 February 2026

|

6 minutes

|

In 2022, the Biden administration in the United States announced a new policy on the dissemination of scientific information. Under the policy, any federally funded research must publish findings on an open platform – without a paywall – and make the underlying scientific data publicly available around the time of publication of the article. By 2023, declared the “Year of Open Science,” the comprehensive initiative was already being put into practice: a growing number of federal agencies, from NASA to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), issued policy guidance and invested in platforms to support open access.

Open science is widely seen as serving the public interest, and it’s easy to understand why. When journals are freely available online, universities, small institutions, and curious readers who can’t afford expensive subscriptions can enjoy direct access to what is happening at the cutting edge of research. Open articles also tend to travel farther: they’re read more widely and cited more often by other scientists. And in the age of artificial intelligence, paywall-free papers are especially valuable—making it easier for large language models and other data-driven tools to scan, search, and analyze the scientific literature.

Moreover, data transparency – both within the scientific community and between researchers and the public – can strengthen trust in research and in science more broadly, by making it easier to scrutinize and verify scientific claims and findings. Although researchers are typically required, when submitting manuscripts to journals, to state how they intend to share their data, this is not always enough. After all, when an article is published behind a paywall, only paying subscribers may be able to examine the underlying raw data.

Open-access journals enable institutions and individuals who cannot afford subscriptions to access the forefront of contemporary research directly. | Elsevier Publishing website | II.studio, Shutterstock

Paying the Piper of Publishing

Many scientific journals are owned by commercial publishers with a profit motive. One way to provide free access for readers is to shift the cost to authors—the researchers themselves—rather than requiring readers to pay. Researchers who want to publish in such journals may be charged substantial submission or publication fees, sometimes reaching thousands of dollars, to cover the costs of publishing and running the journal. In a sense, as surely as physics has laws of conservation, academic publishing follows its own “conservation of profit”: someone has to pay for the article to be published.

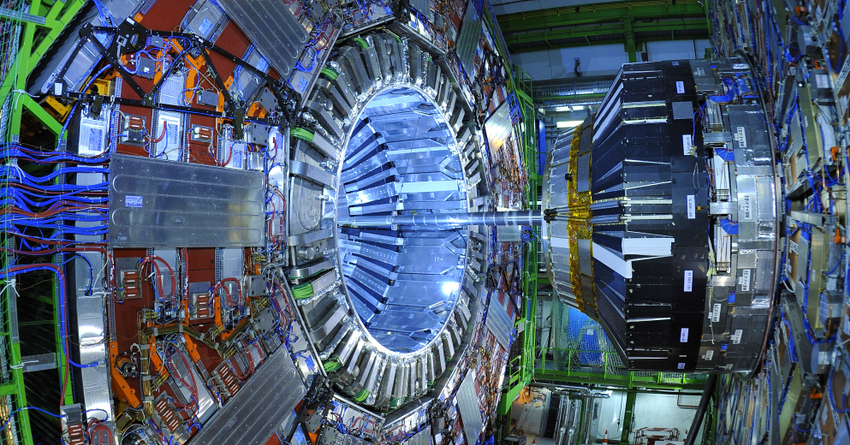

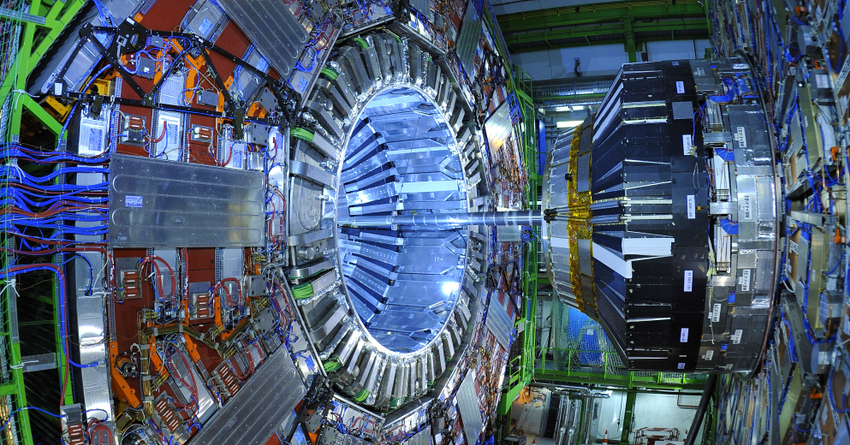

Early in 2025, Nature’s news site reported on an unusual initiative by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, home to the world’s largest particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). As a major research institution – where papers are often produced by collaborations of hundreds, or even thousands, of scientists who publish under a shared author list – CERN is now attempting to use its economic leverage and the sheer volume of high-profile research it generates to push journals toward making those articles openly accessible.

CERN operates a dedicated unit focused exclusively on open science. The policy the organization follows is based on incentivizing journals based on their open-access policies. For example, it offers higher payments to journals that adopt more generous open-access terms, according to clearly defined criteria.

From CERN’s perspective, open access is only one part of a broader agenda. The organization also wants journals to make papers more accessible to readers with disabilities—for example, people with visual impairments—and to promote cultural, national, and ethnic diversity among authors. The underlying premise is that better science is also more inclusive, and more diverse. Journals that score highly on these measures may receive a 15% bonus on payments for CERN-submitted articles, while those with low scores could face a “penalty” of up to 10%. CERN’s size and prestige are what make this kind of hard-nosed negotiating with publishers possible.

CERN operates dedicated units focused exclusively on the coordination and implementation of open science policies. The LHC particle accelerator at CERN | Source: D-VISIONS, Shutterstock

A Broad Collaboration

This initiative sits at the forefront of CERN’s Open Science Office and is tied to a broader alliance of researchers in high-energy physics. In 2012, the Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics (SCOAP3) was established—one of the first coordinated lobbying groups of its kind aimed at scientific journal publishers. Over the years, the consortium has partnered with 11 leading journals that have signaled their willingness to work with researchers on open-access publishing.

SCOAP3 brings together 44 countries and three major scientific organizations, including CERN. The other two are the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and Russia’s Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR). The initiative also includes more than 3,000 libraries worldwide. About three years ago, several major academic publishers – among them Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press – joined the partnership.

Thanks to SCOAP3, more than 80,000 scientific articles have been published to date with free public access, and nearly 100 books have been made available without a paywall. The consortium’s annual budget now exceeds €10 million. Under the new initiative, that budget is expected to grow by roughly 9% per year over the next three years to cover the added costs of incentivizing top-performing journals.

According to Kamran Naim, CERN’s Head of Open Science, the new incentive system is not meant to punish publishers, but to encourage adoption of policies that better serve the public interest in open access. Naim, who is also involved in SCOAP3, adds that CERN aims to demonstrate its commitment to open access not only in words but in action, and is prepared to dedicate the resources needed to ensure the initiative’s success. Naim’s own commitment is longstanding as well: his doctoral dissertation, submitted a few years ago, is focused entirely on the issue of open access to science.

A pioneering lobbying effort aimed at scientific journal publishers. Members of SCOAP3 at a meeting at CERN in 2013 | Rachel Lavy, Anna Pantelia, CERN

Toward a New Publishing Reality?

Experts say CERN’s extraordinary move could reshape the publishing landscape. In their view, few steps are as direct—or as effective—for a research institution seeking to influence journal publishing policy. But not everyone is convinced the implications are entirely positive. Philosopher Peter Suber, who serves as Senior Advisor on Open Access at Harvard University, warns that publishers may come to adopt public-serving open-access policies only when a financial reward is attached. If he is right, CERN may achieve its goals – but with an unintended consequence: smaller research organizations, with far less economic leverage and financial resilience, could be left at a disadvantage.

From the perspective of the publishers themselves, the reactions are mixed. The journals of the American Physical Society (APS) immediately embraced the new policy. In contrast, the large and established publisher Elsevier did not respond to Nature’s inquiries ahead of the publication of the news about a year ago. However, since then, Elsevier has aligned itself with the new policy, and its journals are now also part of the consortium.

Publishers’ reactions, meanwhile, have been mixed. Journals of the American Physical Society (APS) quickly embraced the new policy. Elsevier, the long-established publishing giant, did not respond to Nature’s inquiries ahead of the report published about a year earlier. Since then, however, Elsevier has moved into line with the new approach, and its journals have joined the consortium as well.

CERN’s initiative also echoes a step taken previously by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, whose large-scale investments in science and research have made it an influential player in policy discussions. The foundation recently announced that recipients of its research grants will be required to post their papers in open-access preprint repositories before submitting them to journals. Many researchers already do this voluntarily, but until now no major private research funder had made it a formal, across-the-board requirement.

Respect may have to be earned – but it turns out that information freedom, and scientific freedom, often has to be funded as well. It’s encouraging that some institutions are willing to gamble on bold, potentially transformative steps in the public interest. Time will tell whether the bet pays off.