Cold Outbreaks in a Warming World

Why there is no contradiction between a warming global climate and the occurrence of extreme cold waves, such as the one currently affecting the United States.

3 February 2026

|

7 minutes

|

In recent days, the United States has been gripped by an unusually widespread and long-lasting spell of winter weather, as Arctic air and hazardous snow and ice have affected a huge swath of the country since late January. For more than a week, hundreds of millions of Americans—especially across large parts of the central and eastern U.S.—have faced temperatures plunging to around minus 30°C, along with heavy snow, hail, and ice. Dozens of people have died amid the prolonged storm, hundreds of thousands have lost power, and thousands of flights have been canceled. Damages are estimated at more than $100 billion, and another storm arrived over the weekend. A cold wave of this duration has not been seen in the country for decades.

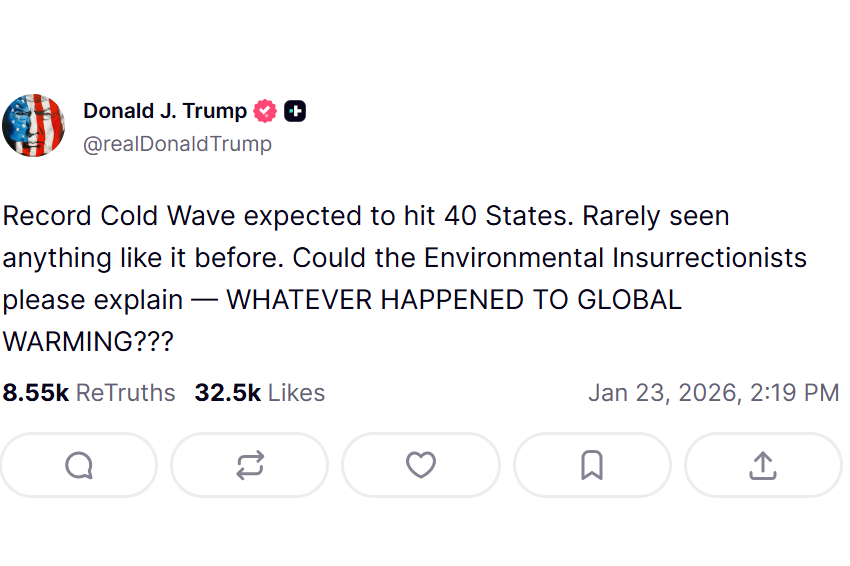

U.S. President Donald Trump questioned on his social network, Truth Social, how such extreme cold can be reconciled with the claim that the world’s climate is warming. This is not the first time he has expressed skepticism about the climate crisis, and recently the United States has also moved to withdraw from major international bodies focused on climate change and environmental protection. But does a cold wave – however severe – actually suggest the world isn’t warming?

Donald Trump: Whatever happened to global warming? The president’s post on Truth Social | Screenshot

Global Climate vs. Local Weather

First of all, global warming refers to the climate of the entire planet, not the weather at a particular time and place. Weather can vary widely between regions, from day to day, between night and day, and across the seasons. Climate change, by contrast, is assessed as an average over the whole globe and over many years. Cold conditions in one location therefore do not necessarily reflect what is happening worldwide.

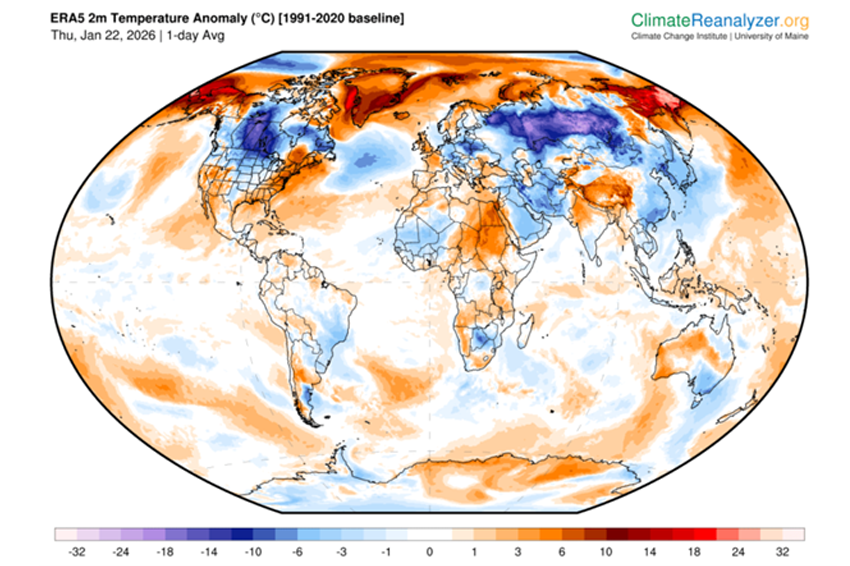

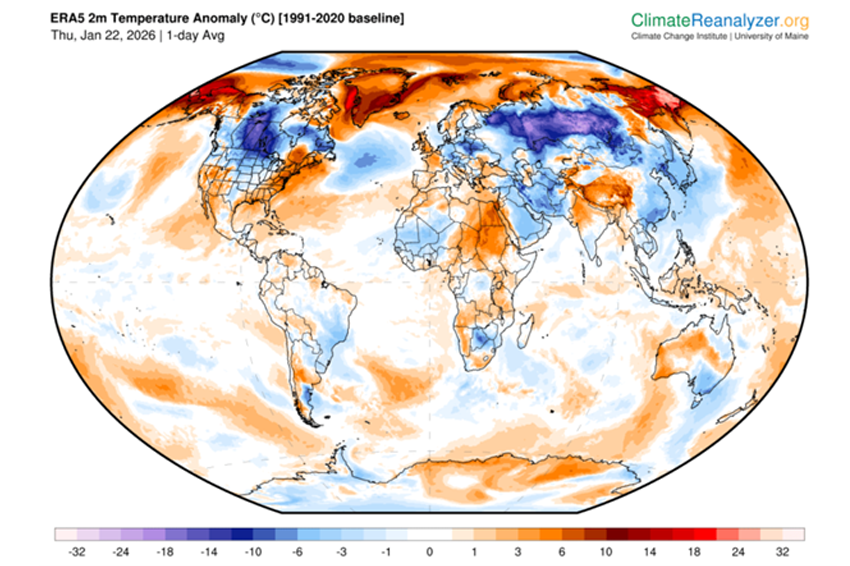

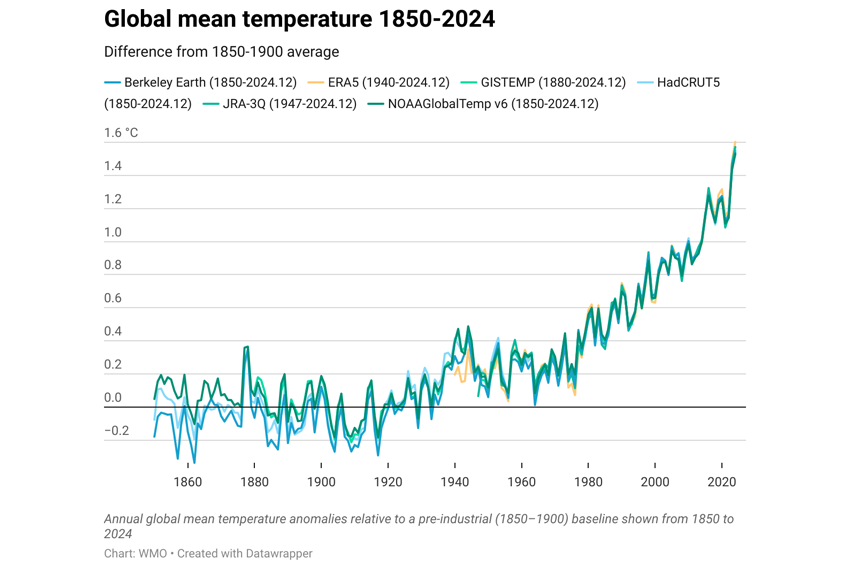

For example, while the United States is experiencing severe cold, neighboring Greenland recorded unusually warm temperatures throughout the week – above freezing much of the time, around 20°C higher than the multi-year average for this period. And when you look at temperatures globally, the average global temperature during the week the cold wave began affecting the U.S. was higher than the 1991–2020 30-year average, not lower. A multi-decade period like this is the standard baseline for calculating climate norms, and in recent decades every year has been warmer than the years before the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century.

While the United States is experiencing severe cold, neighboring Greenland recorded unusually warm temperatures throughout the week. Daily global temperature relative to the multi-year average for the same date, as the cold wave entered the United States | Climate Change Institute, University of Maine

When Arctic Cold Moves South

Global warming (climate change) affects not only average temperatures but also extreme events. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) summarizes the scientific evidence on climate change worldwide. Its assessments show that as the planet warms, heat waves, heavy rainfall and flooding, and droughts increase in frequency and intensity, while cold waves become less frequent overall. At the same time, some regions, such as parts of the United States, may experience intensification of cold waves rather than a decline in cold-wave severity.

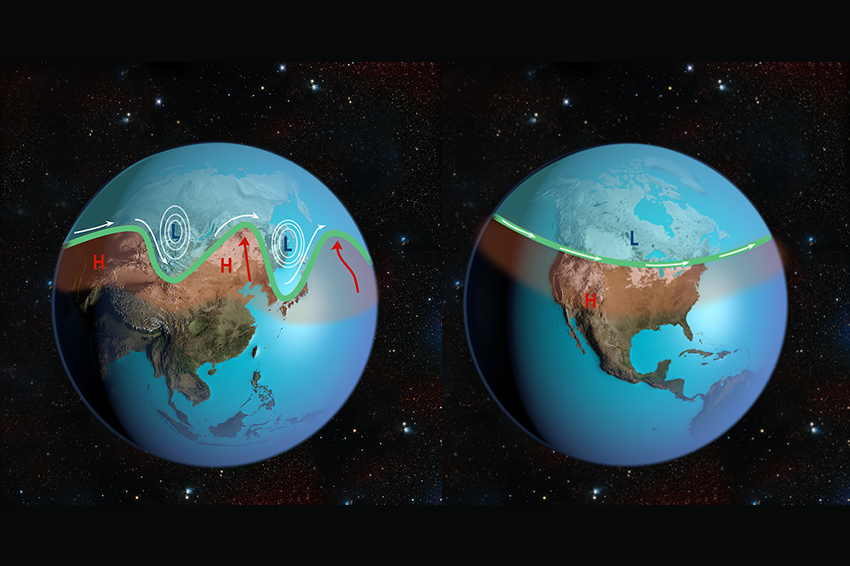

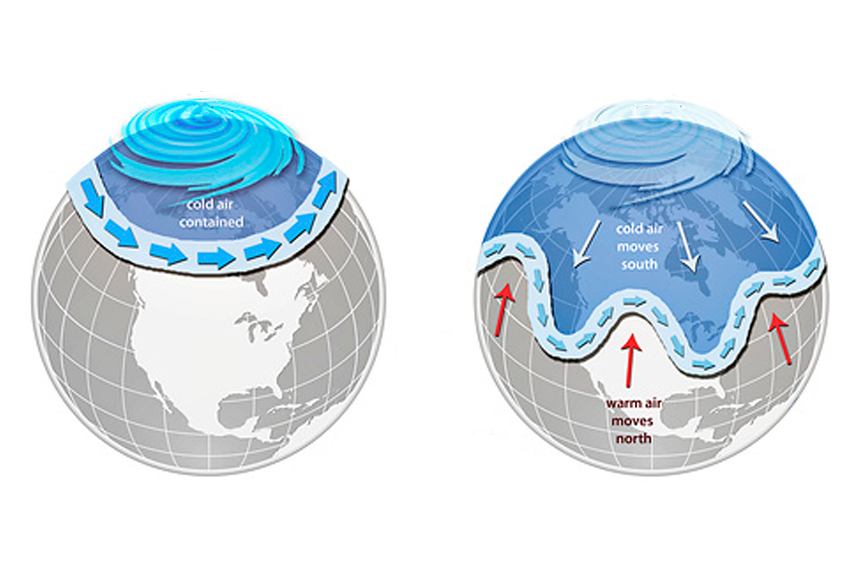

Because Earth is spherical, sunlight strikes the poles at a lower angle. The same solar energy is therefore spread over a larger surface area, so each square meter receives less solar heating. That is why the poles are colder. This temperature difference between the cold poles and the warmer temperate regions creates a pressure gradient that drives atmospheric circulation. Earth’s rotation further shapes this circulation, deflecting winds so that fast-moving air currents flow mainly west to east, circling the poles rather than moving straight north or south. These high-altitude currents—several kilometers above the ground—are called polar jet streams. They help separate cold polar air from warmer air farther south, limiting how easily Arctic air can spill into temperate regions. However, the jet streams can also dip and rise in large, wave-like bends. When they plunge south, they can carry Arctic air into lower latitudes, bringing cold outbreaks to places such as the United States.

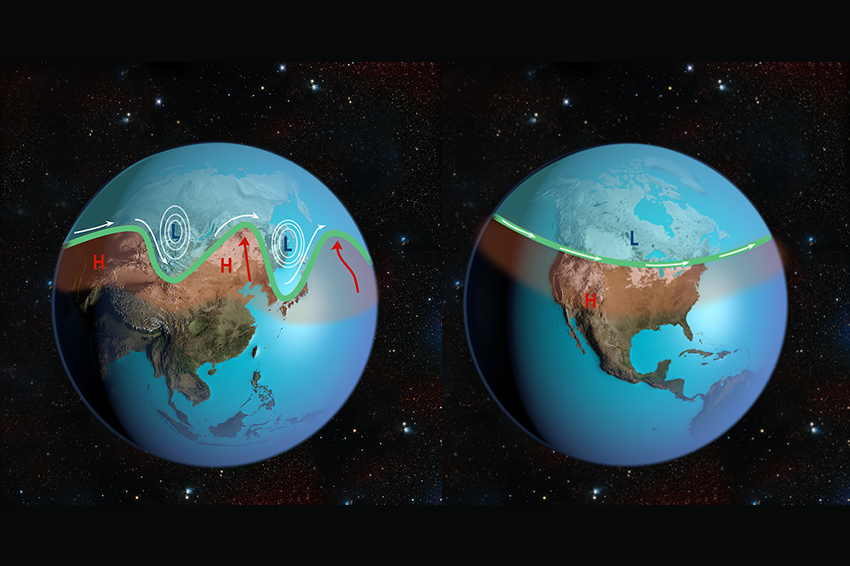

The greater the temperature difference between the pole and the temperate zone, the faster the air movement. For this reason, winter is usually characterized by faster, more stable currents around the North Pole, which help keep the coldest air bottled up and reduce the risk of prolonged deep freezes in North America and Europe. Global warming can change this. The world does not warm evenly, and the poles have warmed much more than many temperate regions. This weakens and slows the jet streams, and when they are slower, it is easier for weather systems to nudge them into larger, more persistent meanders. Those bends can extend far to the south—sometimes reaching as far as Mexico—bringing freezing conditions even to the southern United States. And because the jet stream becomes more wavelike, a southward plunge of cold air over North America can be accompanied by a northward surge of warm air elsewhere, warming places like Greenland at the same time. In addition, because the overall flow of air is relatively slow, the extreme weather patterns it helps produce can linger, allowing extreme conditions to last longer.

When jet streams bend north and south in a wavelike motion, they can allow Arctic cold to reach farther south, including the United States. Fast, stable jet streams (right) and weaker, meandering ones (left) | Karsten Schneider / Science Photo Library

The Polar Vortex: The Big Swirl Above the Arctic

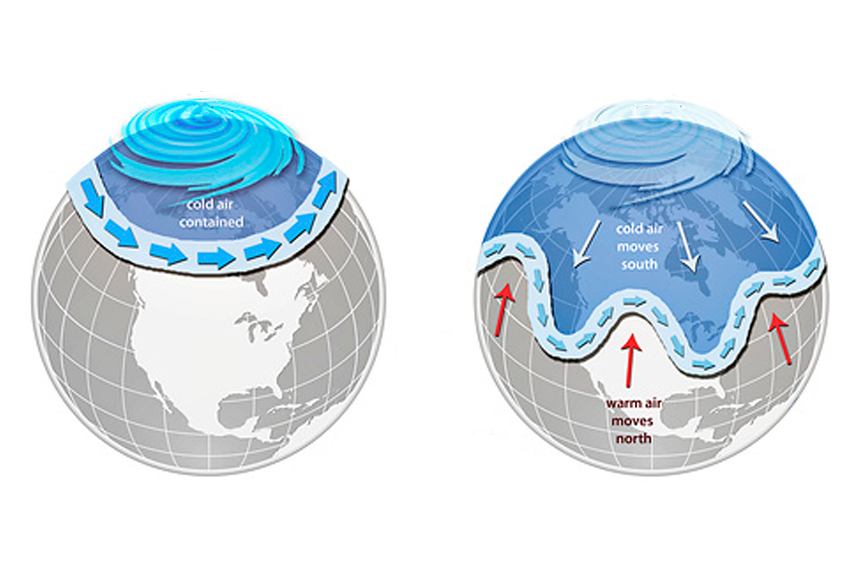

The movement of air from the poles does not end with the jet stream: it is a complex circulation influenced by many factors, and it can sometimes produce especially extreme events. High above the jet stream—tens of kilometers up—a massive vortex of air constantly swirls over the poles. This circulation, known as the polar vortex, is not fully understood, but it clearly helps determine whether polar cold stays near the Arctic or spills southward.

When the vortex is particularly strong, it tends to remain centered over the pole and can suppress large jet-stream waves. This helps maintain a stronger separation between polar cold and the milder air of temperate regions. When the vortex weakens, shifts, stretches, or even changes direction, it can be associated with a rapid warming in the stratosphere—the atmospheric layer above the lowest one. In the weeks following such a warming, the jet stream often develops larger meanders, increasing the likelihood of extreme weather. However, the relationship between the polar vortex and the jet stream is not fully understood.

Amy Butler of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) specializes in these atmospheric patterns. As she puts it : “The polar vortex doesn’t always influence winter weather in the mid-latitudes. When it does, however, the effects can be extreme.” Various forecasts point to a significant disruption of the polar vortex this year. This could bring exceptionally cold temperatures in February across parts of the Northern Hemisphere, but it is not certain. Sometimes the vortex is disrupted without producing extreme weather.

When the vortex is especially strong, it tends to remain close to the pole and reduce the jet stream’s waves (illustration on the left). When the vortex weakens or changes shape, it may increase the jet stream’s meanders and contribute to extreme weather (right) | NOAA

Like the jet stream, the polar vortex may also be influenced by climate change, but it is still unclear to what extent. Butler notes that “even though you have an overall warming trend, you might see an increase in the severity of individual winter weather events in some locations,” Still, she emphasizes that more research is needed to understand what governs polar-vortex behavior, and that there are long-term patterns we do not yet fully understand. “What we see in the record is this very interesting period in the 1990s, when there were no sudden stratospheric warming events observed in the Arctic. In other words, the vortex was strong and stable. But then they started back up again in the late 1990s, and over the next decade there was one almost every year. So there was a window of time in the early 2010s where it seemed like there might be a trend toward weaker, more disrupted or shifted states of the Arctic polar vortex. But it hasn’t continued, and more and more, it’s looking like what seemed to be the beginning of a trend was just natural variability, or maybe just a rebound from the quiet of the 1990s.”

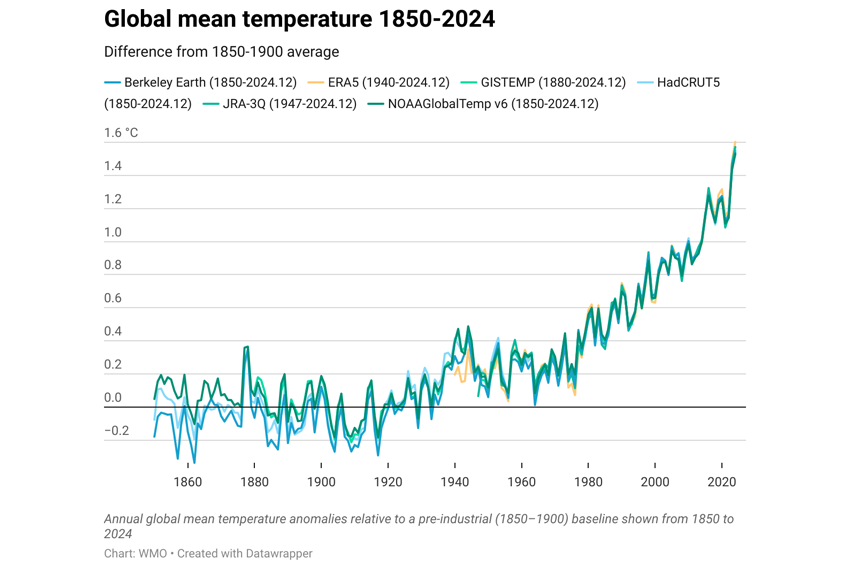

The long-term trend of global warming is sharp and clear: in recent decades, every year has been warmer than the years before the Industrial Revolution. Global average temperature from 1850 to 2020 | World Meteorological Organization

The Climate Crisis Is Here, and the Evidence Is Conclusive

In contrast to the complex, sometimes confusing behavior of the polar vortex, the overall trend of global warming is sharp and unmistakable. Even when some regions experience cold spells, global average temperatures continue to rise. Multiple scientific bodies around the world track global temperature using increasingly sophisticated methods, and their findings are unequivocal: warming is real, and its impacts are already visible. We also know with very high confidence that the primary driver is greenhouse-gas emissions from human activities – especially the burning of fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal.

When the United States, the largest emitter at the time, withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000s, other countries followed suit. Even so, European countries and others stayed in the agreement, which required emissions cuts, and many met their targets. The outcome was far from ideal, but it helped reduce emissions and accelerated the development of low-carbon technologies. Today, the Paris Agreement – which replaced the Kyoto Protocol – faces similar strains after the United States withdrew from it. The hope is that decision-makers around the world will act in line with the scientific consensus, cut greenhouse-gas emissions rapidly, and avert the most severe consequences of the climate crisis. The public, too, can help push this effort forward.